嗯,用户让我帮忙总结一篇文章,控制在100字以内,而且不需要特定的开头。首先,我需要理解文章的内容。看起来这篇文章讲的是ConsentFix这种钓鱼攻击,利用OAuth2.0的授权框架,通过诱导受害者生成授权码,然后获取访问令牌,进而访问微软账户。 用户可能需要一个简洁明了的摘要,用于快速了解攻击机制和影响。他们可能对技术细节不太熟悉,所以总结时要避免使用太多专业术语。 接下来,我要提取关键点:攻击利用OAuth2.0,受害者被引导生成授权码并提交到钓鱼网站,攻击者用这个码获取访问令牌,从而入侵账户。同时,文章还提到了检测和缓解策略。 现在,我需要用简短的语言把这些点整合起来。确保不超过100字,并且直接描述内容,不使用“这篇文章”之类的开头。 最后检查一下是否涵盖了主要攻击步骤、影响以及应对措施。这样用户就能快速掌握文章的核心内容了。 </think> ConsentFix是一种基于OAuth2.0的钓鱼攻击技术,通过诱导受害者生成并提交授权码到恶意网站,获取访问令牌以入侵微软账户。该攻击利用第一方应用的信任机制和Conditional Access绕过特性,在受害者不知情的情况下窃取敏感权限。文章分析了攻击流程、检测方法及缓解策略。 2026-1-29 08:14:4 Author: blog.nviso.eu(查看原文) 阅读量:0 收藏

ConsentFix (a.k.a. AuthCodeFix) is the latest variant of the fix-type phishing attacks, initially identified by Push Security1. In this technique, the adversary tricks the victim into generating an OAuth authorization code that is part of a localhost URL by signing in to the Azure CLI instance (or other vulnerable applications). Then, the victim is instructed to copy that URL and paste it into a phishing website, essentially handing over the authorization code to the adversary, who is now able to exchange it for an access token. Using the access token, the adversary gets access to the victim’s Microsoft account.

In this blog post, we dive into the mechanics of the attack and explore detection and mitigation strategies for it.

OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework

The attack relies heavily on the OAuth2 authorization framework, so to better understand the mechanics, we will briefly go through OAuth2’s inner workings.

OAuth2 (Open Authorization) is a standard authorization framework that allows users to grant third-party applications scoped access to specific resources or data on other services (e.g., Microsoft, Google, Facebook) for a limited amount of time, without sharing their usernames and passwords with those applications.

OAuth2 was developed to prevent users from sharing their credentials with third-party apps that require access to their data as part of their functionality. It lets users grant access via a secure flow managed by a trusted provider (e.g., Microsoft, Google). Users sign in with that provider and approve a request, after which the app receives an access token that permits access only to the required data.

OAuth2 uses the following terms2 to describe the authorization workflow:

- Resource Owner – The user who owns the data that the application wants to access and authorizes the application.

- Client – The application that requests access to the data of the user.

- Authorization Server – The service that authenticates the users and grants access tokens to the application.

- Resource Server – The service that holds the user’s data.

A typical implementation of the OAuth2 authorization flow (Authorization Code Grant) is the following:

Since this attack revolves around Microsoft’s Identity platform, we are also including below the OAuth2 authorization code flow implementation from Microsoft’s documentation3.

ConsentFix Attack Flow and Mechanics

The attack is executed by following multiple steps:

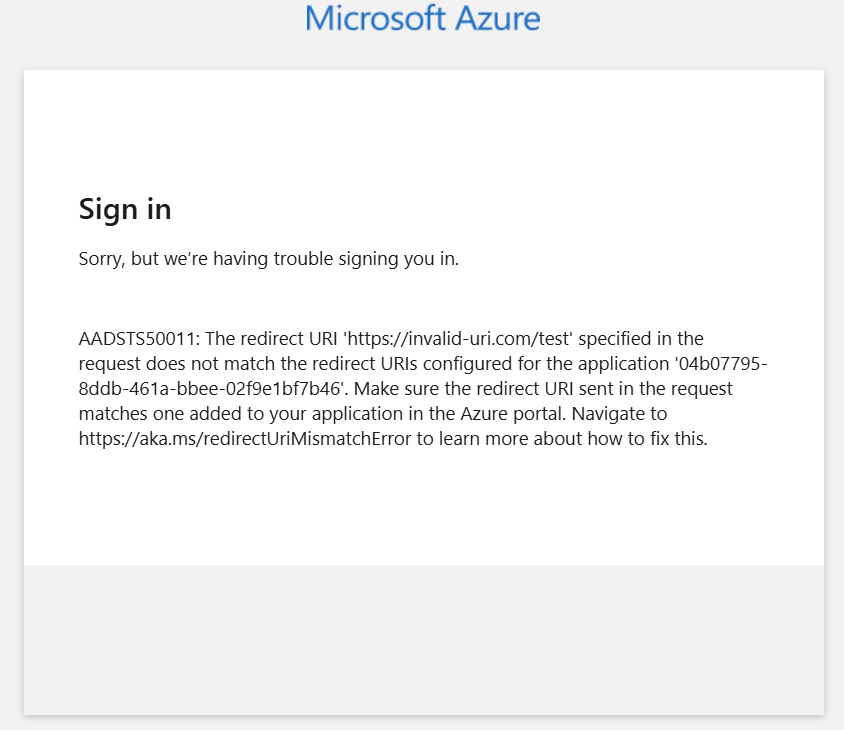

- The adversary compromises (watering hole) or creates a malicious phishing page prompting the victim to enter an email address.

- The victim visits the phishing page, typically via a search engine, and enters their email address.

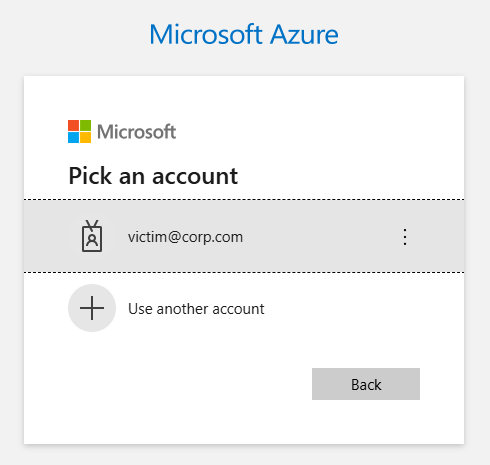

- The victim is redirected to login.microsoftonline.com to authenticate and authorize an application to access their account. If already authenticated, the victim may not need to enter an email, password, or perform MFA, as it is possible to select the existing session/account from a list.

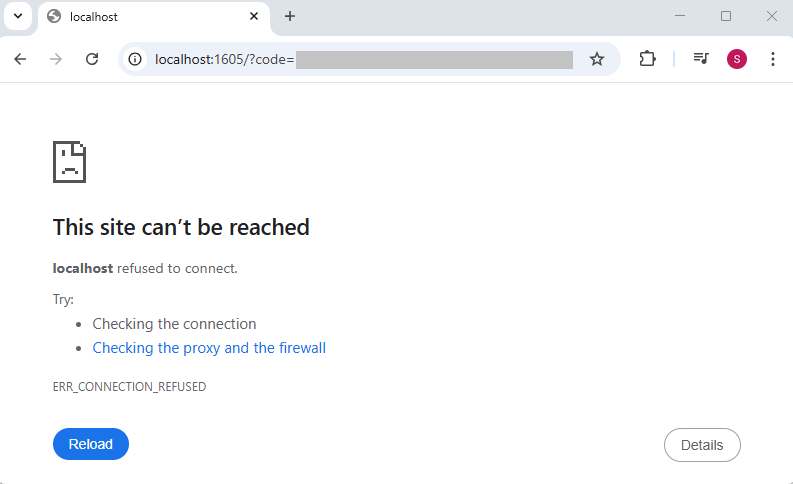

- After authentication and authorization, the victim is redirected to a localhost application URL in the browser. The redirection URL contains an authorization code that would normally be consumed by the legitimate application initiating the flow (step 4 in the authorization workflow). Because the authorization flow did not start from a legitimate application and no application is listening on localhost to receive the code, the victim encounters a 404 “This site can’t be reached” message. The adversary exploits this by instructing the victim to copy and paste the URL containing the authorization code back into the phishing site if that error appears.

- With the authorization code, the adversary exchanges it using Microsoft’s /oauth2/v2.0/token API for an access token.

- Using the access token (a.k.a. Bearer token), the adversary accesses the user’s Microsoft account and resources.

Why does this attack work?

The original blog post mentions that Azure CLI was the primary target of the ConsentFix attack, and there is a reason for that. Azure CLI is a first-party Microsoft application, which means it is implicitly trusted by Entra ID. As a result, users are not shown an “I accept these permissions” consent prompt during authentication.

First-party applications, like Azure CLI, are pre-consented by default. This allows them to request permissions without triggering a user consent dialog or requiring administrator approval. This behavior is by design, as Microsoft wants tools such as Azure CLI, Azure PowerShell, and Visual Studio to work seamlessly for every user without administrative intervention. The attack will also work against any user in the tenant, regardless of whether they have ever used the targeted application before.

In addition, the attack is feasible because it can bypass Conditional Access controls. While the user’s initial sign-in may require credentials and MFA (if no active session exists) and is governed by Conditional Access policies, once the adversary obtains the authorization code, they can exchange it for an access token without triggering a new Conditional Access evaluation. This allows the adversary to obtain tokens from non-compliant devices or untrusted locations, but also creates detection opportunities, as we will see below.

The trick, however, lies in selecting a return URI that is valid (meaning allowed by the application) but still returns a 404 “This site can’t be reached” message to the victim. Each application maintains its own list of permitted return URIs that can be chosen. If the adversary selects an invalid return URI, the victim will instead encounter an error similar to the following.

Localhost is an obvious choice for applications that accept it, since the adversary can select a port where no service is expected to be listening. For other applications, the adversary can choose alternative return URIs that may be even more convincing. For example, with the Aadrm Admin Powershell, selecting the URI https://aadrm.com/adminpowershell will redirect the victim to a legitimate page, with the authorization code included in the URL.

Affected First Party Applications

Azure CLI is not the only vulnerable application to this attack. Entrascopes.com by Fabian Bader4 is an excellent resource that includes a full list of first-party apps that are vulnerable to the ConsentFix attack and have known Conditional Access bypasses5, for example:

- Microsoft Azure CLI: 04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46

- Microsoft Azure PowerShell: 1950a258-227b-4e31-a9cf-717495945fc2

- Visual Studio: 872cd9fa-d31f-45e0-9eab-6e460a02d1f1

- Visual Studio Code: aebc6443-996d-45c2-90f0-388ff96faa56

- Microsoft SharePoint Online Management Shell: 9bc3ab49-b65d-410a-85ad-de819febfddc

- Microsoft Power Query for Excel: a672d62c-fc7b-4e81-a576-e60dc46e951d

- Microsoft Teams: 1fec8e78-bce4-4aaf-ab1b-5451cc387264

- Microsoft Whiteboard Client: 57336123-6e14-4acc-8dcf-287b6088aa28

- Microsoft Flow Mobile PROD-GCCH-CN: 57fcbcfa-7cee-4eb1-8b25-12d2030b4ee0

- Enterprise Roaming and Backup: 60c8bde5-3167-4f92-8fdb-059f6176dc0f

- Aadrm Admin Powershell: 90f610bf-206d-4950-b61d-37fa6fd1b224

If you remove the Conditional Access Policy bypass requirement, however, the vulnerable applications are more.

Steps to Replicate

We can easily replicate the attack to identify detection opportunities. We will split the tests into two phases: one performed as the victim and another performed as the adversary, ideally from a different IP or location.

Perform as the Victim

When the victim visits the phishing page and enters an email address, they are redirected to login.microsoftonline.com to authenticate and authorize an application to access the account. The URL they are redirected to for requesting the authorization code has the following format6:

https://login.microsoftonline.com/organizations/oauth2/authorize?

client_id=04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46

&response_type=code

&redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Flocalhost%3A1605%2F

&prompt=select_account

&login_hint[email protected]| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| client_id | The application ID of the targeted app. In the example above, we are using the ID for the Azure CLI app, but it can be any of the vulnerable applications mentioned above. |

| response_type | This must be set to code for the authorization code flow. |

| redirect_uri | The redirect_uri of the application, where authentication responses can be sent and received. This needs to be set to localhost and a random port. |

| prompt | Indicates the type of user interaction that is required. select_account lists all the accounts that are in session, remembered account, or an option to choose to use a different account. |

| login_hint | This is used to pre-fill the username and email address fields on the sign-in page for the user. This is populated with the email address that the victim enters on the phishing page. |

Copy the request above into your browser. In a real attack scenario, the victim would be redirected to that URL once they entered their email address on the phishing page.

Authenticate using your Microsoft account, or click on your account if there is an active session.

The browser redirects you to the redirect_uri URL value. That localhost URL includes the authorization code. This is the URL that the victim is instructed to paste into the phishing page.

The localhost redirect URL has the following format:

http://localhost:1605/?

code=<authorization_code>

&session_state=<session_id>The session_state parameter includes the sessionID value, which can be used to search in the SignInLogs table for the sign-in activity that was just performed.

Perform as the Adversary

The next steps are performed by the adversary. To replicate, ideally use a different IP address and location. Using the authorization code provided by the victim, the adversary would perform the following request to receive an access token.

curl.exe -X POST https://login.microsoftonline.com/<common|tenant_id>/oauth2/v2.0/token

-H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded"

-d "client_id=04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46"

-d "scope=https://graph.microsoft.com/.default"

-d "code=<authorization_code>"

-d "redirect_uri=http://localhost:1605/"

-d "grant_type=authorization_code"| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| client_id | The application ID of the targeted app. In the example above, we are using the ID for the Azure CLI app, but it can be any of the vulnerable applications we mentioned above. Must be the same as the one in the first request. |

| scope | This parameter is a Microsoft extension to the authorization code flow. This extension allows apps to declare the resource they want the token for during the token redemption step. |

| code | The authorization code captured by the victim. |

| redirect_uri | The redirect_uri of the application, where authentication responses can be sent and received. This needs to be set to localhost and a random port. Must be the same as the one in the first request. |

| grant_type | Must be authorization_code for the authorization code flow. |

We perform the request, and we get back an access token:

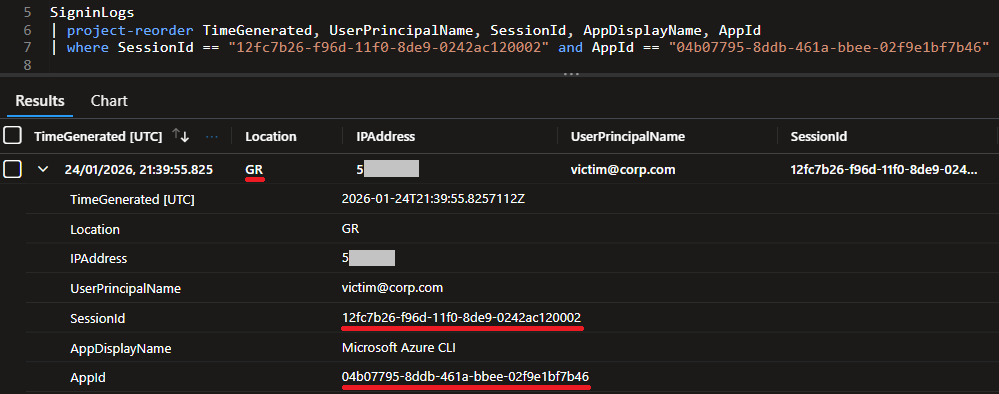

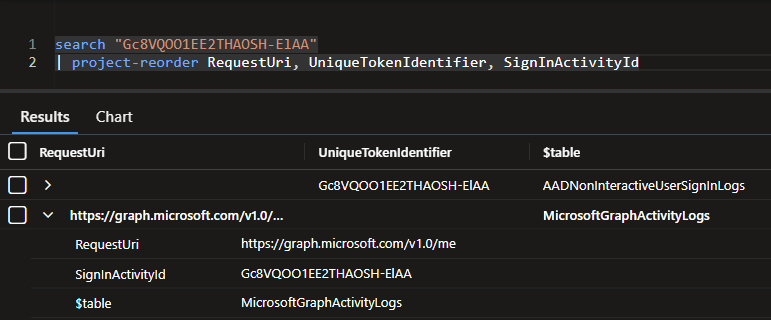

This activity is logged in the AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs table, and we can easily find it using the session ID and the app ID from the previous step.

Using the access token, the adversary can perform actions using the victim’s account. For example:

curl.exe https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/me -H "Authorization: Bearer <access_token>"Digging further into this, however, is out of scope for this blog post.

Detection and Hunting Opportunities

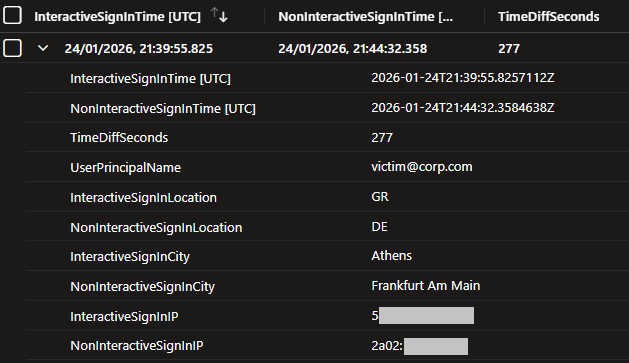

It is clear now from our tests above that the two sign-in events share the same session ID, user principal name, and application ID. In addition, the interactive login (SignInLogs) precedes the non-interactive login (AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs).

To detect this activity, we create a query that correlates successful interactive and non-interactive sign-ins sharing the same SessionId, AppId, and UserPrincipalName for the specified lookback period across the “affected_application_ids“. It then flags country, city, or IP mismatches occurring within a 10-minute window.

The query can be tuned to allowlist locations (countries), cities, or IP addresses and can also limit the comparison of the sign-ins to location (country) or city.

let affected_application_ids = dynamic([

"04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46", // Microsoft Azure CLI

"1950a258-227b-4e31-a9cf-717495945fc2", // Microsoft Azure PowerShell

"872cd9fa-d31f-45e0-9eab-6e460a02d1f1", // Visual Studio

"aebc6443-996d-45c2-90f0-388ff96faa56", // Visual Studio Code

"9bc3ab49-b65d-410a-85ad-de819febfddc", // Microsoft SharePoint Online Management Shell

"a672d62c-fc7b-4e81-a576-e60dc46e951d", // Microsoft Power Query for Excel

"1fec8e78-bce4-4aaf-ab1b-5451cc387264", // Microsoft Teams

"57336123-6e14-4acc-8dcf-287b6088aa28", // Microsoft Whiteboard Client

"57fcbcfa-7cee-4eb1-8b25-12d2030b4ee0 ", //Microsoft Flow Mobile PROD-GCCH-CN

"60c8bde5-3167-4f92-8fdb-059f6176dc0f", // Enterprise Roaming and Backup

"90f610bf-206d-4950-b61d-37fa6fd1b224" // Aadrm Admin Powershell

]);

let lookback= 30d;

let sign_in_diff_max_seconds = 600; // max time between interactive and not interactive login

let sign_in_diff_min_seconds = 10; // min time between interactive login and time that the victim takes to copy-paste the URL. If actions occurs within a few seconds it is probably automated.

let compare_location = true;

let compare_city = false;

let non_interactive_locations_allowlist = dynamic([]);

let non_interactive_cities_allowlist = dynamic([]);

let non_interactive_ips_allowlist = dynamic([]);

SigninLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(lookback)

| where AppId in (affected_application_ids)

| where ResultType == 0

| project

InteractiveSignInTime = CreatedDateTime, // really important to use CreatedDateTime NOT TimeGenerated

UserPrincipalName,

InteractiveSignInLocation = Location,

InteractiveSignInCity = tostring(parse_json(LocationDetails).city),

InteractiveSignInIP = IPAddress,

InteractiveSignInUserAgent = UserAgent,

InteractiveSignInResourceIdentity = ResourceIdentity,

InteractiveSignInResourceDisplayName = ResourceDisplayName,

InteractiveSignInUniqueTokenIdentifier = UniqueTokenIdentifier,

AppId,

AppDisplayName,

SessionId

| join kind=inner (AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(lookback)

| where AppId in (affected_application_ids)

| where ResultType == 0

| project

NonInteractiveSignInTime = CreatedDateTime, // really important to use CreatedDateTime NOT TimeGenerated

UserPrincipalName,

NonInteractiveSignInLocation = Location,

NonInteractiveSignInCity = tostring(parse_json(LocationDetails).city),

NonInteractiveSignInIP = IPAddress,

NonInteractiveSignInUserAgent = UserAgent,

NonInteractiveSignInResourceIdentity = ResourceIdentity,

NonInteractiveSignInResourceDisplayName = ResourceDisplayName,

NonInteractiveSignInUniqueTokenIdentifier = UniqueTokenIdentifier,

AppId,

AppDisplayName,

SessionId

)

on UserPrincipalName, AppId, SessionId

| where NonInteractiveSignInLocation !in (non_interactive_locations_allowlist)

| where NonInteractiveSignInCity !in (non_interactive_cities_allowlist)

| where NonInteractiveSignInIP !in (non_interactive_ips_allowlist)

| where NonInteractiveSignInTime > InteractiveSignInTime // Interactive sign in precedes the non-interactive sign in

| extend TimeDiffSeconds = datetime_diff("second", NonInteractiveSignInTime, InteractiveSignInTime)

| where TimeDiffSeconds between (sign_in_diff_min_seconds .. sign_in_diff_max_seconds)

| where InteractiveSignInIP != NonInteractiveSignInIP

| where iif(compare_location, InteractiveSignInLocation != NonInteractiveSignInLocation and isnotempty(InteractiveSignInLocation) and isnotempty(NonInteractiveSignInLocation), true) == true

| where iif(compare_city, InteractiveSignInCity != NonInteractiveSignInCity and isnotempty(InteractiveSignInCity) and isnotempty(NonInteractiveSignInCity), true) == true

| project

InteractiveSignInTime,

NonInteractiveSignInTime,

TimeDiffSeconds,

UserPrincipalName,

InteractiveSignInLocation,

NonInteractiveSignInLocation,

InteractiveSignInCity,

NonInteractiveSignInCity,

InteractiveSignInIP,

NonInteractiveSignInIP,

InteractiveSignInUserAgent,

NonInteractiveSignInUserAgent,

InteractiveSignInResourceIdentity,

NonInteractiveSignInResourceIdentity,

InteractiveSignInResourceDisplayName,

NonInteractiveSignInResourceDisplayName,

InteractiveSignInUniqueTokenIdentifier,

NonInteractiveSignInUniqueTokenIdentifier,

AppDisplayName,

AppIdIt is essential to use the CreatedDateTime field for comparing interactive and non-interactive logins. The TimeGenerated field can be affected by ingestion delays and may lead to misleading results.

Although the detection captures the activity, it can produce false positives. To improve accuracy in your environment, consider allow-listing trusted locations, cities, IP addresses, user principal names, and user agents. Additionally, tuning the sign_in_diff_min_seconds variable in the query can reduce false positives. If the interactive and non-interactive login occur within a few seconds, they are likely automated and not a result of manually copy-pasting the URL.

After a successful trigger additional investigation can be performed by using the UniqueTokenIdentifier of the non-interactive sign-in.

Mitigations

There are a few ways to mitigate the ConsentFix attack and reduce its attack surface or chance of exploitation.

The first solution would be to create service principals for the affected Microsoft first-party applications and require user assignment before they can be used7. That way, access becomes limited to explicitly assigned users or groups, and you can block any opportunistic attack paths towards random users, as the adversary would have to know or guess which users are eligible to use those first-party applications. This disrupts the ConsentFix attack at the first step. This solution would block unauthorized users from being phished, but if an assigned user is targeted, the attack would still work.

Another approach would be to define Conditional Access policies that limit sign-ins for those applications to trusted locations and managed or compliant devices8. This would greatly reduce the attack surface.

Lastly, token protection9 , might be an option to reduce token replay attacks by ensuring only device-bound sign-in session tokens are accepted. The feature however, requires Microsoft Entra ID P1 licenses and is supported on Windows 10 or newer and Windows Server 2019 or newer OS. Also a limited number of applications and resources are supported as of this moment.

Countermeasures would first require scoping the organization for legitimate application users in order to exclude them from the configurations described above and avoid any disruptions to your operations.

Closing Thoughts

ConsentFix is a particularly interesting but also concerning fix-type attack. The attack can affect any user, even if they have not used one of the vulnerable applications before, and can bypass MFA, Conditional Access, and device compliance checks. It also weaponizes the legitimate OAuth2 authorization flow through social engineering, and unlike its other variations, is executed entirely on the victim’s browser. This makes the detection of this attack particularly tricky, as it blends in with normal authentication traffic and is unlikely to be detected reliably by most security tools.

The mitigations described above should limit the attack surface enough so that opportunistic abuse is nullified and targeted attempts are no longer practical for most adversaries. They should also be coupled with sign-in activity monitoring for behaviors such as non-interactive sign-ins to CLI tools from unexpected locations, or sign in anomalies between interactive and non-interactive sign-ins within the same session, as shown in the query provided above.

References

- https://pushsecurity.com/blog/consentfix ↩︎

- https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6749#section-1.1 ↩︎

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/v2-oauth2-auth-code-flow ↩︎

- https://entrascopes.com/?bypass=true&authcodeFix=true ↩︎

- http://cloudbrothers.info/en/conditional-access-bypasses/ ↩︎

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/v2-oauth2-auth-code-flow#request-an-authorization-code ↩︎

- https://docs.azure.cn/en-us/entra/identity-platform/howto-restrict-your-app-to-a-set-of-users ↩︎

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/conditional-access/concept-conditional-access-cloud-apps ↩︎

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/conditional-access/concept-token-protection ↩︎

About the Author

Stamatis Chatzimangou

Stamatis is a member of the Threat Detection Engineering team at NVISO’s CSIRT & SOC and is mainly involved in use case research and development.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh