OSS-Fuzz在开源项目中发现大量漏洞,但持续模糊测试并非万能。案例显示代码覆盖率低、外部依赖未覆盖及编码逻辑关注不足导致漏洞存活,需结合人工监督和改进策略提升安全。 2025-12-29 22:2:6 Author: github.blog(查看原文) 阅读量:0 收藏

Even when a project has been intensively fuzzed for years, bugs can still survive.

OSS-Fuzz is one of the most impactful security initiatives in open source. In collaboration with the OpenSSF Foundation, it has helped to find thousands of bugs in open-source software.

Today, OSS-Fuzz fuzzes more than 1,300 open source projects at no cost to maintainers. However, continuous fuzzing is not a silver bullet. Even mature projects that have been enrolled for years can still contain serious vulnerabilities that go undetected. In the last year, as part of my role at GitHub Security Lab, I have audited popular projects and have discovered some interesting vulnerabilities.

Below, I’ll show three open source projects that were enrolled in OSS-Fuzz for a long time and yet critical bugs survived for years. Together, they illustrate why fuzzing still requires active human oversight, and why improving coverage alone is often not enough.

Gstreamer

GStreamer is the default multimedia framework for the GNOME desktop environment. On Ubuntu, it’s used every time you open a multimedia file with Totem, access the metadata of a multimedia file, or even when generating thumbnails for multimedia files each time you open a folder.

In December 2024, I discovered 29 new vulnerabilities, including several high-risk issues.

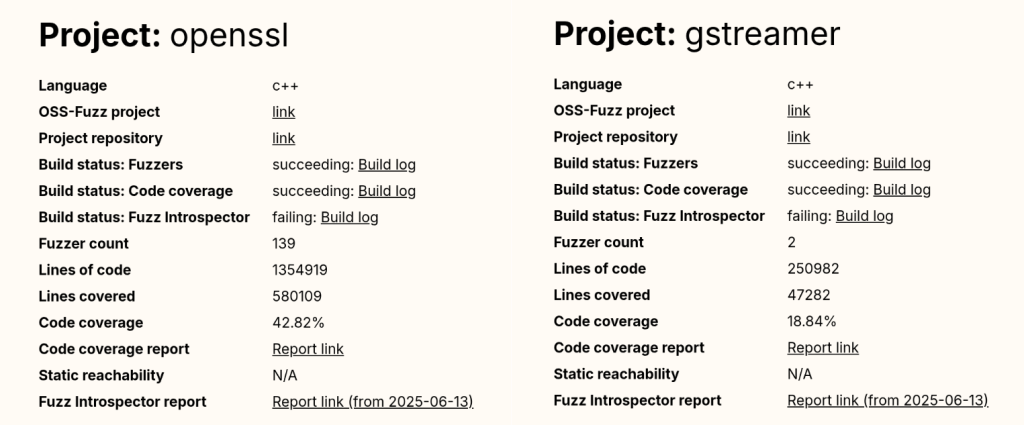

To understand how 29 new vulnerabilities could be found in a software that has been continuously fuzzed for seven years, let’s have a look at the public OSS-Fuzz statistics available here. If we look at the GStreamer stats, we can see that it has only two active fuzzers and a code coverage of around 19%. By comparison, a heavily researched project like OpenSSL has 139 fuzzers (yes, 139 different fuzzers, that is not a typo).

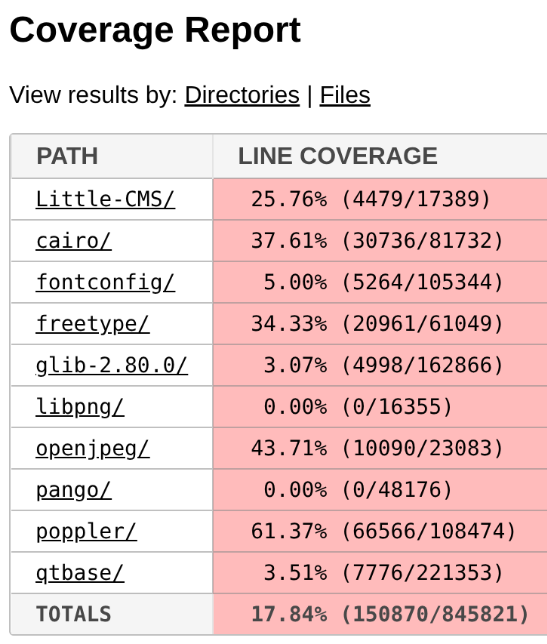

And the popular compression library bzip2 reports a code coverage of 93.03%, a number that is almost five times higher than GStreamer’s coverage.

Even without being a fuzzing expert, we can guess that GStreamer’s numbers are not good at all.

And this brings us to our first reason: OSS-Fuzz still requires human supervision to monitor project coverage and to write new fuzzers for uncovered code. We have good hope that AI agents could soon help us fill this gap, but until that happens, a human needs to keep doing it by hand.

The other problem with OSS-Fuzz isn’t technical. It’s due to its users and the false sense of confidence they get once they enroll their projects. Many developers are not security experts, so for them, fuzzing is just another checkbox on their security to-do list. Once their project is “being fuzzed,” they might feel it is “protected by Google” and forget about it. Even if the project actually fails during the build stage and isn’t being fuzzed at all (which happens to more than one project in OSS-Fuzz).

This shows that human security expertise is still required to maintain and support fuzzing for each enrolled project, and that doesn’t scale well with OSS-Fuzz’s success!

Poppler

Poppler is the default PDF parser library in Ubuntu. It’s the library used to render PDFs when you open them with Evince (the default document viewer in Ubuntu versions prior to 25.04) or Papers (the default document viewer for GNOME desktop and the default document viewer from newer Ubuntu releases).

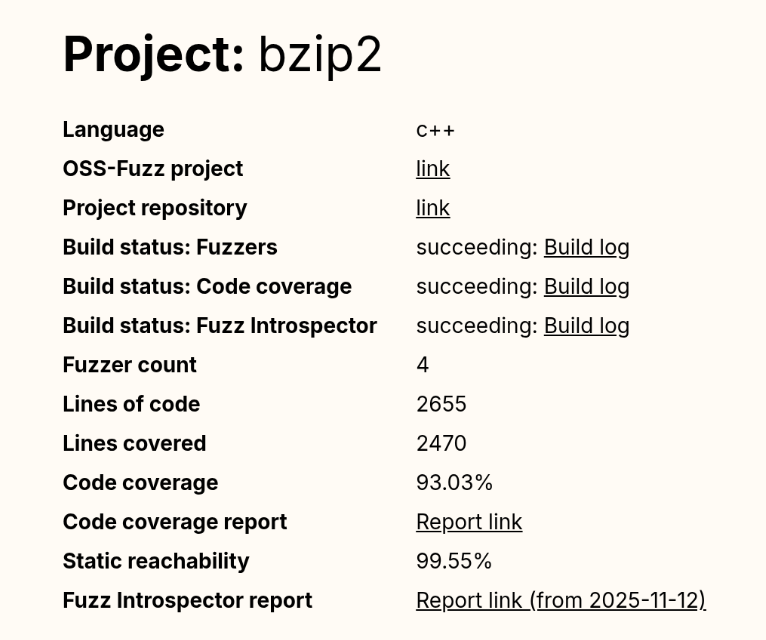

If we check Poppler stats in OSS-Fuzz, we can see it includes a total of 16 fuzzers and that its code coverage is around 60%. Those are quite solid numbers; maybe not at an excellent level, but certainly above average.

That said, a few months ago, my colleague Kevin Backhouse published a 1-click RCE affecting Evince in Ubuntu. The victim only needs to open a malicious file for their machine to be compromised. The reason a vulnerability like this wasn’t found by OSS-Fuzz is a different one: external dependencies.

Poppler relies on a good bunch of external dependencies: freetype, cairo, libpng… And based on the low coverage reported for these dependencies in the Fuzz Introspector database, we can safely say that they have not been instrumented by libFuzzer. As a result, the fuzzer receives no feedback from these libraries, meaning that many execution paths are never tested.

But it gets even worse: Some of Evince’s default dependencies aren’t included in the OSS-Fuzz build at all. That’s the case with DjVuLibre, the library where I found the critical vulnerability that Kevin later exploited.

DjVuLibre is a library that implements support for the DjVu document format, an open source alternative to PDF that was popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s for compressing scanned documents. It has become much less widely used since the standardization of the PDF format in 2008.

The surprising thing is that while this dependency isn’t included among the libraries covered by OSS-Fuzz, it is shipped by default with Evince and Papers. So these programs were relying on a dependency that was “unfuzzed” and at the same time, installed on millions of systems by default.

This is a clear example of how software is only as secure as the weakest dependency in its dependency graph.

Exiv2

Exiv2 is a C++ library used to read, write, delete, and modify Exif, IPTC, XMP, and ICC metadata in images. It’s used by many mainstream projects such as GIMP and LibreOffice among others.

Back in 2021, my teammate Kevin Backhouse helped improve the security of the Exiv2 project. Part of that work included enrolling Exiv2 in OSS-Fuzz for continuous fuzzing, which uncovered multiple vulnerabilities, like CVE-2024-39695, CVE-2024-24826, and CVE-2023-44398.

Despite the fact that Exiv2 has been enrolled in OSS-Fuzz for more than three years, new vulnerabilities have still been reported by other vulnerability researchers, including CVE-2025-26623 and CVE-2025-54080.

In that case, the reason is a very common scenario when fuzzing media formats: Researchers always tend to focus on the decoding part, since it is the most obviously exploitable attack surface, while the encoding side receives less attention. As a result, vulnerabilities in the encoding logic can remain unnoticed for years.

From a regular user perspective, a vulnerability in an encoding function may not seem particularly dangerous. However, these libraries are often used in many background workflows (such as thumbnail generation, file conversions, cloud processing pipelines, or automated media handling) where an encoding vulnerability can be more critical.

The five-step fuzzing workflow

At this point it’s clear that fuzzing is not a magic solution that will protect you from everything. To assure minimum quality, we need to follow some criteria.

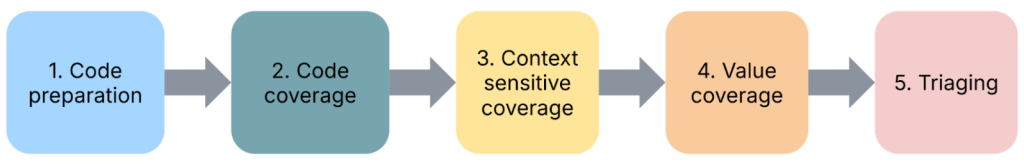

In this section, you’ll find the fuzzing workflow I’ve been using with very positive results in the last year: the five-step fuzzing workflow (preparation – coverage – context – value – triaging).

Step 1: Code preparation

This step involves applying all the necessary changes to the target code to optimize fuzzing results. These changes include, among others:

- Removing checksums

- Reducing randomness

- Dropping unnecessary delays

- Signal handling

If you want to learn more about this step, check out this blog post.

Step 2: Improving code coverage

From the previous examples, it is clear that if we want to improve our fuzzing results, the first thing we need to do is to improve the code coverage as much as possible.

In my case, the workflow is usually an iterative process that looks like this:

Run the fuzzers > Check the coverage > Improve the coverage > Run the fuzzers > Check the coverage > Improve the coverage > …

The “check the coverage” stage is a manual step where i look over the LCOV report for uncovered code areas and the “improve the coverage” stage is usually one of the following:

- Writing new fuzzing harnesses to hit new code that would otherwise be impossible to hit

- Creating new input cases to trigger corner cases

For an automated, AI-powered way of improving code coverage, I invite you to check out the Plunger module in my FRFuzz framework. FRFuzz is an ongoing project I’m working on to address some of the caveats in the fuzzing workflow. I will provide more details about FRFuzz in a future blog post.

Another question we can ask ourselves is: “When can we stop increasing code coverage?” In other words, when can we say the coverage is good enough to move on to the next steps?

Based on my experience fuzzing many different projects, I can say that this number should be >90%. In fact, I always try to reach that level of coverage before trying other strategies, or even before enabling detection tools like ASAN or UBSAN.

To reach this level of coverage, you will need to fuzz not only the most obvious attack vectors such as decoding/demuxing functions, socket-receivers, or file-reading routines, but also the less obvious ones like encoders/muxers, socket-senders, and file-writing functions.

You will also need to use advanced fuzzing techniques like:

- Fault injection: A technique where we intentionally introduce unexpected conditions (corrupted data, missing resources, or failed system calls) to see how the program behaves. So instead of waiting for real failures, we simulate these failures during fuzzing. This helps us to uncover bugs in execution paths that are rarely executed, such as:

- Failed memory allocations (malloc returning NULL)

- Interrupted or partial reads/writes

- Missing files or unavailable devices

- Timeouts or aborted network connections

A good example of fault injection is the Linux kernel Fault injection framework

- Snapshot fuzzing: Snapshot fuzzing takes a snapshot of the program at any interesting state, so the fuzzer can then restore this snapshot before each test case. This is especially useful for stateful programs (operating systems, network services, or virtual machines). Examples include the QEMU mode of AFL++ and the AFL++ Nyx mode.

Step 3: Improving context-sensitive coverage

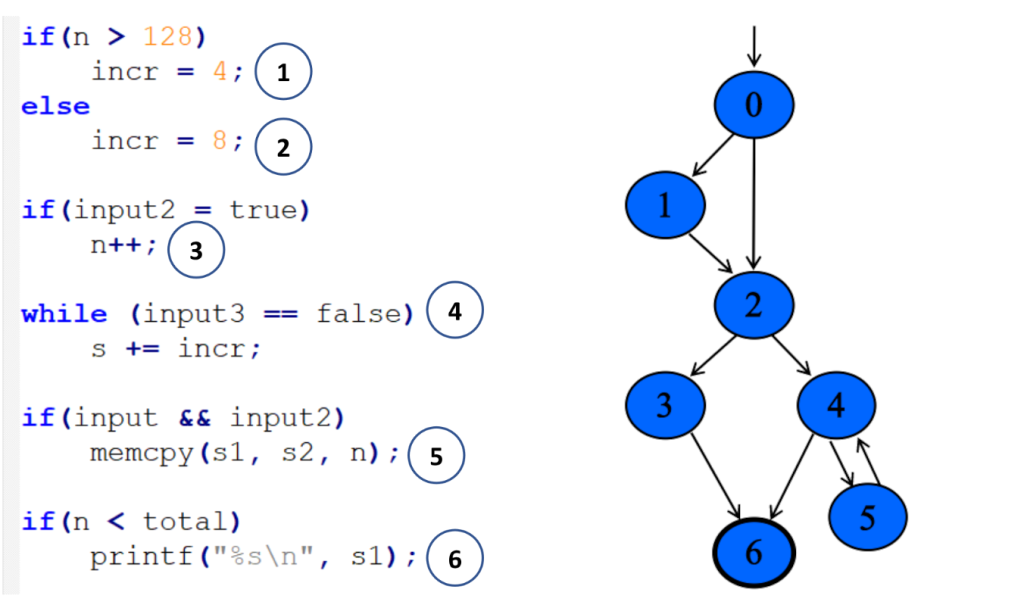

By default, the most common fuzzers (aka AFL++, libfuzzer, and honggfuzz) track the code coverage at the edge level. We can define an “edge” as a transition between two basic blocks in the control-flow graph. So if execution goes from block A to block B, the fuzzer records the edge A → B as “covered.” For each input the fuzzer runs, it updates a bitmap structure marking which edges were executed as a 0 or 1 value (currently implemented as a byte in most fuzzers).

In the following example, you can see a code snippet on the left and its corresponding control-flow graph on the right:

Each numbered circle corresponds to a basic block, and the graph shows how those blocks connect and which branches may be taken depending on the input. This approach to code coverage has demonstrated to be very powerful given its simplicity and efficiency.

However, edge coverage has a big limitation: It doesn’t track the order in which blocks are executed.

So imagine you’re fuzzing a program built around a plugin pipeline, where each plugin reads and modifies some global variables. Different execution orders can lead to very different program states, while the edge coverage can still look identical. Since the fuzzer thinks it has already explored all the paths, the coverage-guided feedback won’t keep guiding it, and the chances of finding new bugs will drop.

To address this, we can make use of context-sensitive coverage. Context-sensitive coverage not only tracks which edges were executed, but it also tracks what code was executed right before the current edge.

For example, AFL++ implements two different options for context-sensitive coverage:

- Context- sensitive branch coverage: In this approach, every function gets its own unique ID. When an edge is executed, the fuzzer takes the IDs from the current call stack, hashes them together with the edge’s identifier, and records the combined value.

You can find more information on AFL++ implementation here

- N-Gram Branch Coverage: In this technique, the fuzzer combines the current location with the previous N locations to create a context-augmented coverage entry. For example:

- 1-Gram coverage: looks at only the previous location

- 2-Gram coverage: considers the previous two locations

- 4-Gram coverage: considers the previous four

You can see how to configure it in AFL++ here

In contrast to edge coverage, it’s not realistic to aim for a coverage >90% when using context-sensitive coverage. The final number will depend on the project’s architecture and on how deep into the call stack we decide to track. But based on my experience, anything above 60% can be considered a very good result for context-sensitive coverage.

Step 4: Improving value coverage

To explain this section, I’m going to start with an example. Take a look at the following web server code snippet:

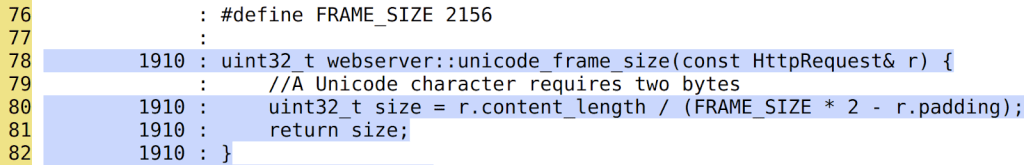

Here we can see that the function unicode_frame_size has been executed 1910 times. After all those executions, the fuzzer didn’t find any bugs. It looks pretty secure, right?

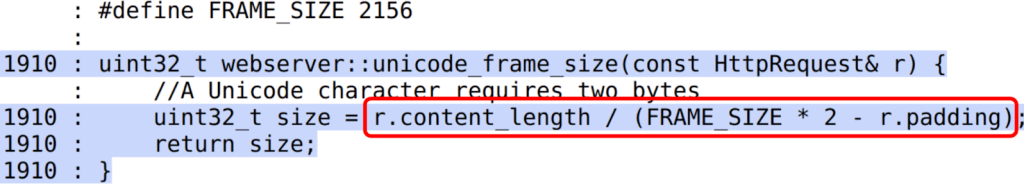

However, there is an obvious div-by-zero bug when r.padding == FRAME_SIZE * 2:

Since the padding is a client-controlled field, an attacker could trigger a DoS in the webserver, sending a request with a padding size of exactly 2156 * 2 = 4312 bytes. Pretty annoying that after 1910 iterations the fuzzer didn’t find this vulnerability, don’t you think?

Now we can conclude that even having 100% code coverage is not enough to guarantee that a code snippet is free of bugs. So how do we find these types of bugs? And my answer is: Value Coverage.

We can define value coverage as the coverage of values a variable can take. Or in other words, the fuzzer will now be guided by variable value ranges, not just by control-flow paths.

If, in our earlier example, the fuzzer had value-covered the variable r.padding, it could have reached the value 4312 and in turn, detected the divide-by-zero bug.

So, how can we make the fuzzer to transform variable values in different execution paths? The first naive implementation that came to my mind was the following one:

inline uint32_t value_coverage(uint32_t num) {

uint32_t no_optimize = 0;

if (num < UINT_MAX / 2) {

no_optimize += 1;

if(num < UINT_MAX / 4){

no_optimize += 2;

...

}else{

no_optimize += 3

...

}

}else{

no_optimize += 4;

if(num < (UINT_MAX / 4) * 3){

no_optimize += 5;

...

}else{

no_optimize += 6;

...

}

}

return no_optimize;

}In this code, I implemented a function that maps different values of the variable num to different execution paths. Notice the no_optimize variable to avoid the compiler from optimizing away some of the function’s execution paths.

After that, we just need to call the function for the variable we want to value-cover like this:

static volatile uint32_t vc_noopt;

uint32_t webserver::unicode_frame_size(const HttpRequest& r) {

//A Unicode character requires two bytes

vc_noopt = value_coverage(r.padding); //VALUE_COVERAGE

uint32_t size = r.content_length / (FRAME_SIZE * 2 - r.padding);

return size;

}Given the huge number of execution paths this can generate, you should only apply it to certain variables that we consider “strategic.” By strategic, I mean those variables that can be directly controlled by the input and that are involved in critical operations. As you can imagine, selecting the right variables is not easy and it mostly comes down to the developers and researchers experience.

The other option we have to reduce the total number of execution paths is by using the concept of “buckets”: Instead of testing all 2^32 possible values of a 32 bits integer, we can group those values into buckets, where each bucket transforms into a single execution path. With this strategy, we don’t need to test every single value and can still achieve good results.

These buckets also don’t need to be symmetrically distributed across the full range. We can emphasize certain subranges by creating smaller buckets or, create bigger buckets for ranges we are not so interested in.

Now that I’ve explained the strategy, let’s take a look at what real-world options we have to get value coverage in our fuzzers:

- AFL++ CmpLog / Clang trace-cmp: These focus on tracing comparison values (values used in calls to

==,memcmp, etc.). They wouldn’t help us find our divide-by-zero bug, since they only track values used in comparison instructions. - Clang trace-div + libFuzzer -use_value_profile=1: This one would work in our example, since it traces values involved in divisions. But it doesn’t give us variable-level granularity, so we can only limit its scope by source file or function, not by specific variable. That limits our ability to target only the “strategic” variables.

To overcome these problems with value coverage, I wrote my own custom implementation using the LLVM FunctionPass functionality. You can find more details about my implementation by checking the FRFuzz code here.

The last mile: almost undetectable bugs

Even when you make use of all up-to-date fuzzing resources, some bugs can still survive the fuzzing stage. Below are two scenarios that are especially hard to tackle with fuzzing.

Big input cases

These are vulnerabilities that require very large inputs to be triggered (on the order of megabytes or even gigabytes). There are two main reasons they are difficult to find through fuzzing:

- Most fuzzers cap the maximum input size (for example 1 MB in the case of AFL), because larger inputs lead to longer execution times and lower overall efficiency.

- The total possible input space is exponential: O(256ⁿ), where n is the size in bytes of the input data. Even when coverage-guided fuzzers use heuristic approaches to tackle this problem, fuzzing is still considered a sub-exponential problem, with respect to input size. So the probability of finding a bug decreases rapidly as the input size grows.

For example, CVE-2022-40303 is an integer overflow bug affecting libxml2 that requires an input larger than 2GB to be triggered.

These are vulnerabilities that can’t be triggered within the typical per-execution time limit used by fuzzers. Keep in mind that fuzzers aim to be as fast as possible, often executing hundreds or thousands of test cases per second. In practice, this means per-execution time limits on the order of 1–10 milliseconds, which is far too short for some classes of bugs.

As an example, my colleague Kevin Backhouse found a vulnerability in the Poppler code that fits well in this category: the vulnerability is a reference-count overflow that can lead to a use-after-free vulnerability.

Reference counting is a way to track how many times a pointer is referenced, helping prevent vulnerabilities such as use-after-free or double-free. You can think of it as a semi-manual form of garbage collection.

In this case, the problem was that these counters were implemented as 32-bit integers. If an attacker can increment the counter up to 2^32 times, it will wrap the value back to 0 and then trigger a use-after-free in the code.

Kevin wrote a proof of concept that demonstrated how to trigger this vulnerability. The only problem is that it turned out to be quite slow, making exploitation unrealistic: The PoC took 12 hours to finish.

That’s an extreme example of a bug that needs “extra time” to manifest, but many vulnerabilities require at least seconds of execution to trigger. Even that is already beyond the typical limits of existing fuzzers, which usually set per-execution timeouts well under one second.

That’s why finding vulnerabilities that require seconds to trigger is almost a chimera for fuzzers. And this effectively discards a lot of real-world exploitation scenarios from what fuzzers can find.

It’s important to note that although fuzzer timeouts frequently turn out to be false alarms, it’s still a good idea to inspect them. Occasionally they expose real performance-related DoS bugs, such as quadratic loops.

How to proceed in these cases?

I would like to be able to give you a how-to guide on how to proceed in these scenarios. But the reality is we don’t have effective fuzzing strategies for these case corners yet.

At the moment, mainstream fuzzers are not able to catch these kinds of vulnerabilities. To find them, we usually have to turn to other approaches: static analysis, concolic (symbolic + concrete) testing, or even the old-fashioned (but still very profitable) method of manual code review.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that fuzzing is one of the most powerful options we have for finding bugs in complex software, it’s not a fire-and-forget solution. Continuous fuzzing can identify vulnerabilities, but it can also fail to detect some attack vectors. Without human-driven work, entire classes of bugs have survived years of continuous fuzzing in popular and crucial projects. This was evident in the three OSS-Fuzz examples above.

I proposed a five-step fuzzing workflow that goes further than just code coverage, covering also context-sensitive coverage and value coverage. This workflow aims to be a practical roadmap to ensure your fuzzing efforts go beyond the basics, so you’ll be able to find more elusive vulnerabilities.

If you’re starting with open source fuzzing, I hope this blog post helped you better understand current fuzzing gaps and how to improve your fuzzing workflows. And if you’re already familiar with fuzzing, I hope it gives you new ideas to push your research further and uncover bugs that traditional approaches tend to miss.

Want to learn how to start fuzzing? Check out our Fuzzing 101 course at gh.io/fuzzing101 >

Written by

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh