About six months ago we released a security advisory on this blog about vulnerabilities in Airoha-based Bluetooth headphones and earbuds. Back then, we didn’t release all technical details to give vendors more time to release updates and users time to patch their devices. Around the time of the initial partial disclosure in the beginning of June, Airoha put out an SDK release for their customers that mitigates the vulnerabilities. Now, half a year later, we finally want to publish the technical details and release a tool for researchers and users to continue researching and check whether their devices are vulnerable.

This blog post is about CVE-2025-20700, CVE-2025-20701, and CVE-2025-20702.

Alongside this blog post, we also released a white paper. It contains some more technical details, as well as information on how to check whether your device might be affected.

Introduction

Bluetooth headphones and earbuds are some of the most widely used Bluetooth peripherals. As such, they are an interesting target for security research. What is possible when such a device is compromised? What could an attacker achieve? Are Bluetooth headphones a target that’s worth putting in time and resources? After initially discovering an interesting target we were asking ourselves these questions.

During our research we identified three vulnerabilities in a common set of Bluetooth SoCs that are used in a variety of Bluetooth headphones and earbuds. In this blog post, we want to provide a brief technical overview over the vulnerabilities, outline the implications, and discuss the difficulties of disclosure and patching. Alongside this post, we also release a white paper and RACE Toolkit, a tool for researchers and users to verify whether a device is vulnerable. There’s also a talk at 39c3, if you prefer watching videos.

Airoha is a vendor that, amongst other things, builds Bluetooth SoCs and offers reference designs and implementations incorporating these chips. They have become a large supplier in the Bluetooth audio space, especially in the area of True Wireless Stereo (TWS) earbuds. Several reputable headphone and earbud vendors have built products based on Airoha’s SoCs and reference implementations using Airoha’s SDK. If you are wearing earbuds right now, there is a non-zero chance they are running an Airoha chip.

In previous Bluetooth related research we stumbled upon a pair of such headphones. During the process of obtaining the firmware for further research we initially discovered the custom Bluetooth protocol called RACE. We found that this protocol has various powerful capabilities, such as allowing us to read from and write to arbitrary locations in both flash and RAM. Additionally, it was exposed over Bluetooth BR/EDR (also known as Bluetooth Classic) and Bluetooth Low Energy. In both cases, pairing was not required. As such, an attacker within Bluetooth range can connect to the device and manipulate RAM and flash contents without prior authentication.

The lack of pairing does not only enable unauthenticated attackers to use the RACE protocol, it constitutes a vulnerability on its own. An attacker can connect to the device and, for example, use the Bluetooth Hands-Free Profile (HfP) to send or receive audio. This might allow eavesdropping via the device’s microphone.

Background

Before we get into the technical details of the vulnerability, here’s a quick refresher about some Bluetooth terminology. If you’re already familiar with Bluetooth pairing, RFCOMM, and GATT, or if the Bluetooth Core specification is part of you nighttime reading, then feel free to skip to the next section.

Bluetooth is effectively two logically independent protocol stacks operating on the 2.4 GHz ISM band: Bluetooth BR/EDR, also known as Bluetooth Classic, and the newer, low-power optimized Bluetooth Low Energy, often referred to as BLE.

Pairing

Bluetooth devices use pairing to establish shared key material for authentication and encryption. In Bluetooth Classic, pairing occurs during connection establishment through the Link Manager Protocol (LMP). The output of pairing is a Link Key. This Link Key is stored on the Host and provided to the controller whenever a secure connection is to be established.

In BLE, pairing is handled by the Security Manager Protocol (SMP) operating over a fixed L2CAP channel. One major difference here is that in BLE, the pairing is performed on the host part of the stack, in Bluetooth Classic on the controller part.

As we’ll see in the following section, the Airoha-based devices we checked often didn’t enforce authentication for either of the two technologies.

Bluetooth Addressing

Every Bluetooth device is identified at the Link Layer by a Bluetooth Device Address (often referred to as BD_ADDR). This address works similarly to MAC addresses in other wireless systems. It is six bytes long for both Bluetooth Classic and BLE. However, there are some differences in addressing in these two technologies.

In Bluetooth Classic, the address is (or should be) globally unique and assigned by the manufacturer. The first 24 bits of the address contain a manufacturer identifier (the OUI – Organizationally Unique Identifier), the other bits are device specific. This address is static and is required to establish a connection with the device. Knowledge of the device address can sometimes be beneficial for an attacker. Even when a device is not discoverable, the knowledge of the address is enough to establish a connection if the device is connectable. The static nature of the address can also become an issue in regard to privacy.

BLE supports various types of addresses. A Public Device Address that is similar to the BD_ADDR in Bluetooth Classic or a type of Random Device Addresses.

A Random Device Address may be either static or private. Private addresses are regenerated periodically to prevent long-term tracking and come in two forms:

-

Resolvable Private Addresses (RPA), which include a hash derived from the device’s Identity Resolving Key (IRK). RPAs can be recognized by paired devices but appear random to others.

-

Non-Resolvable Private Addresses (NRPA), which are generated randomly and cannot be resolved by any party, used primarily for anonymous advertising.

In dual-mode devices that support both Bluetooth Classic and BLE, these addressing systems are independent. A single physical device therefore typically has two addresses: one Classic BD_ADDR and one BLE address (public or random).

RFCOMM

RFCOMM provides a byte-stream transport that emulates a serial interface over Bluetooth Classic. It operates on top of L2CAP. RFCOMM supports multiple logical data channels multiplexed over a single Bluetooth connection. Channels can be identified via their UUID. RFCOMM often serves as a transparent transport for applications expecting a serial-like interface over a Bluetooth connection.

GATT

In BLE, application data is mainly exchanged through the Generic Attribute Profile (GATT). GATT operates on top of the Attribute Protocol (ATT), which provides basic operations, such as Read, Write, or Notify over a fixed L2CAP channel.

A GATT server can expose multiple services that are identified by a UUID. Each service in turn can hold one or more characteristics that are also identified by a UUID. The characteristics can have different access configuration, such as whether they are readable, writable, subscribable, or whether a secure connection is required to interact with them.

A GATT client can discover and enumerate available services and interact with them by issuing ATT requests or subscribing to notifications.

In real-world applications, GATT often serves the purpose of an underlying layer for a byte-stream transport (similar to RFCOMM or L2CAP in Bluetooth Classic). This stems from the fact that, in BLE, RFCOMM or L2CAP are not always directly accessible on the application layer. To establish a byte-stream transport, a characteristic that allows reading and writing, or subscribing and writing is created. Sending data then works by writing to the characteristic, receiving data by receiving subscription notification.

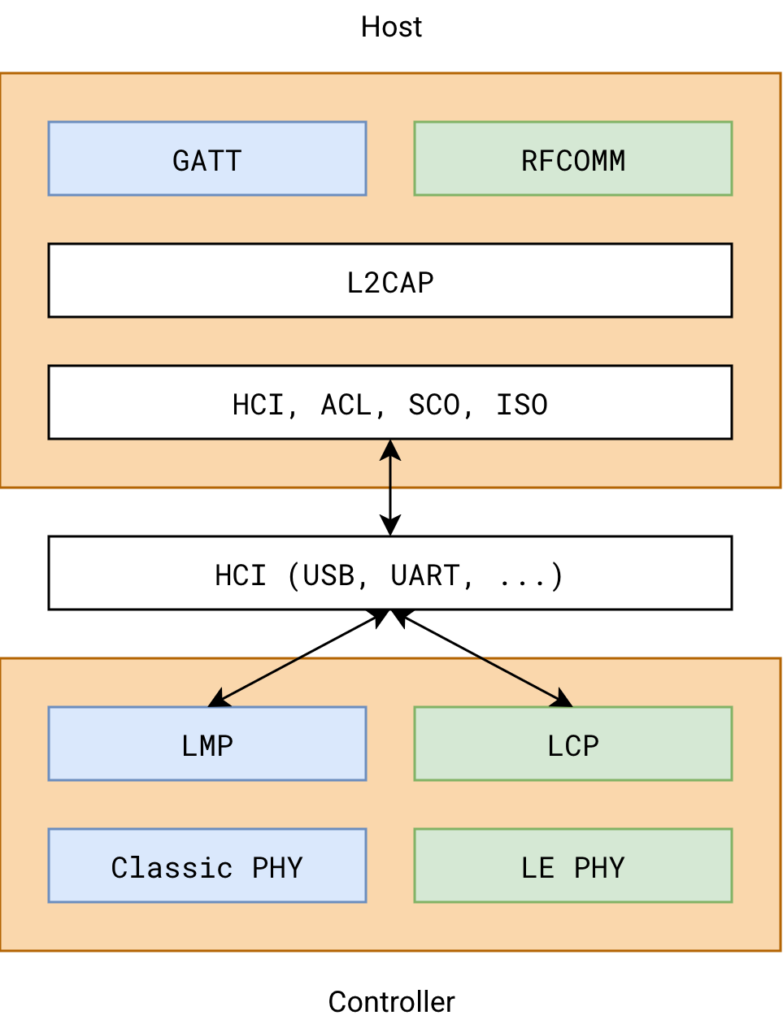

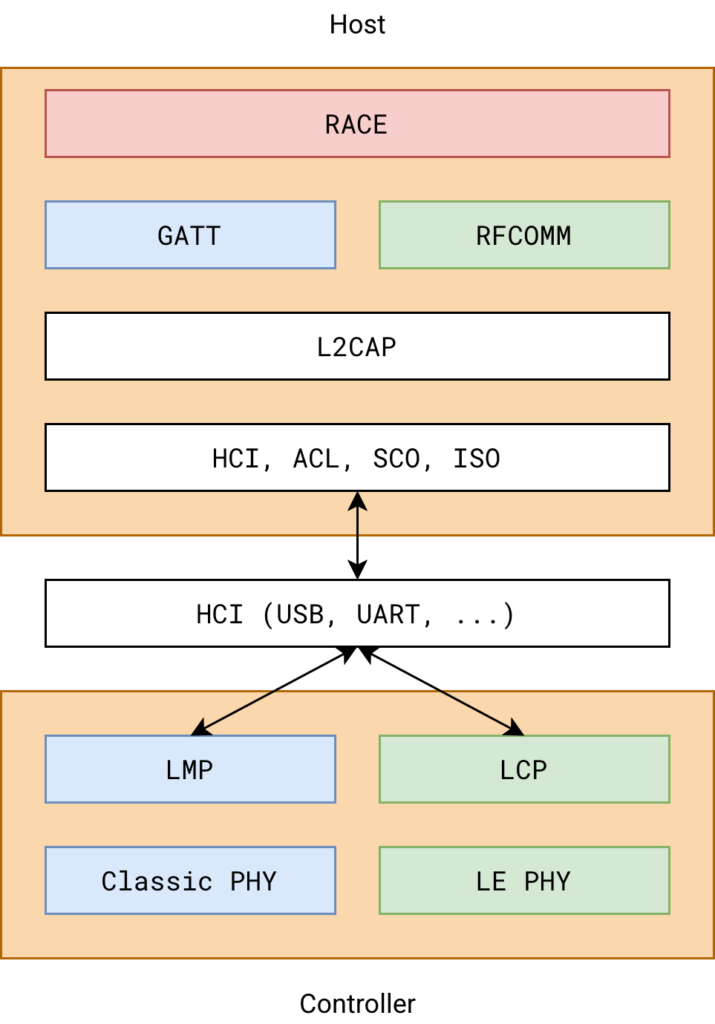

The image below depicts a simplified high level Bluetooth stack, where the blue components are BLE components, and the green ones related to Bluetooth Classic1.

Alright, now that we went over the basics, let’s get into the vulnerabilities!

Missing Bluetooth Pairing

In practice, Bluetooth security is largely invisible to users. Pairing happens once, and usually it happened a long time ago. After that, reconnecting happens silently and automatic. If a device reconnects successfully, it is assumed to be legitimate.

This assumption is not unreasonable when both sides of the connection are well-designed and properly authenticated. The problem arises when one side accepts incoming connections without prior pairing. Or, as we will see later on, when pairing information can be stolen, and a trusted device impersonated.

In the course of analyzing Airoha-based headphones, we discovered that many devices accept Bluetooth Low Energy and Bluetooth Classic connections without enforcing authentication. Any nearby device can connect, interact with exposed services, and in some cases issue critical commands, all without pairing, bonding, or user interaction.

One possible scenario is that an attacker can connect to a pair of headphones and sniff and record the microphone. However, the implications largely depend on the scenario and the target device itself. If the device only allows one Bluetooth connection at a time, and the owner is currently listening to music, they will notice the connection drop. If the device accepts multiple connections, the original audio connection is still likely to drop when the microphone is enabled on the attacker connection.

Depending on the functionalities of the target device, unauthenticated Bluetooth connections might give the attacker other capabilities.

Airoha issued two separate CVEs for the Bluetooth authentication issue. One for Bluetooth Classic, and one for BLE:

- CVE-2025-20700: Missing Authentication for GATT Services

- CVE-2025-20701: Missing Authentication for Bluetooth BR/EDR

During our survey, we found some Airoha-based devices that were not vulnerable to the Bluetooth Classic vulnerability (CVE-2025-20701). A notable example here are the Jabra Elite 8 Active earbuds. We assume that these vendors adapted the SDK code to enforce pairing, or changed default configurations of the SDK to secure the device. For some models we found that the pairing was unreliable. Sometimes, the device did not accept HfP or RACE connections without prior pairing, sometimes it did. An example for such a device are the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds.

This authentication issue becomes more interesting when we consider that it exposes the RACE protocol to unauthenticated attackers in proximity of the device.

The RACE Protocol

We initially discovered the RACE protocol during our Bluetooth Auracast research. To play around with Auracast, we acquired a MoerLab Auracast transmitter and a compatible pair of headphones.

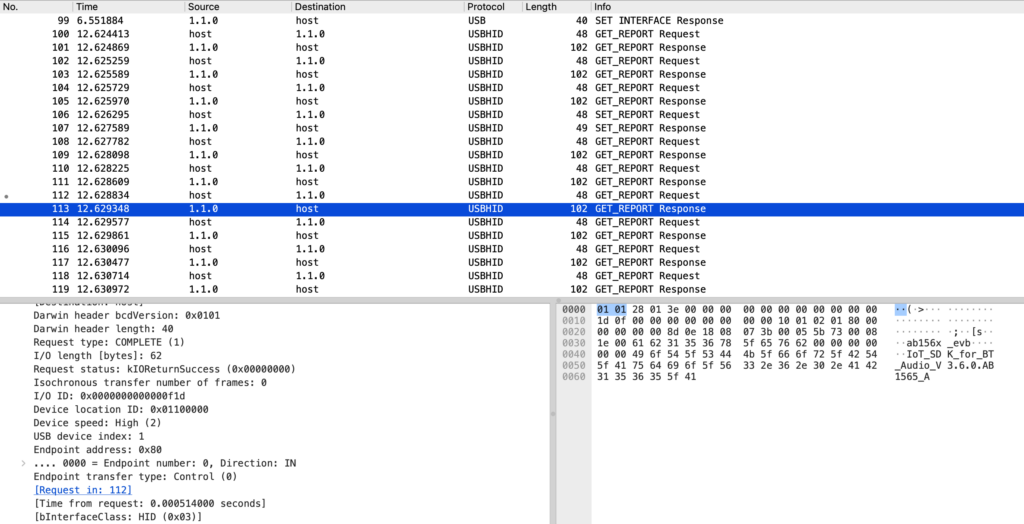

While analyzing the USB traffic between the transmitter and its Windows configuration and firmware update utility, we observed a stream of interesting USB HID packets. This looked like a custom protocol. The screenshot below shows a USB capture. In this case, the response to the get buildversion command is shown.

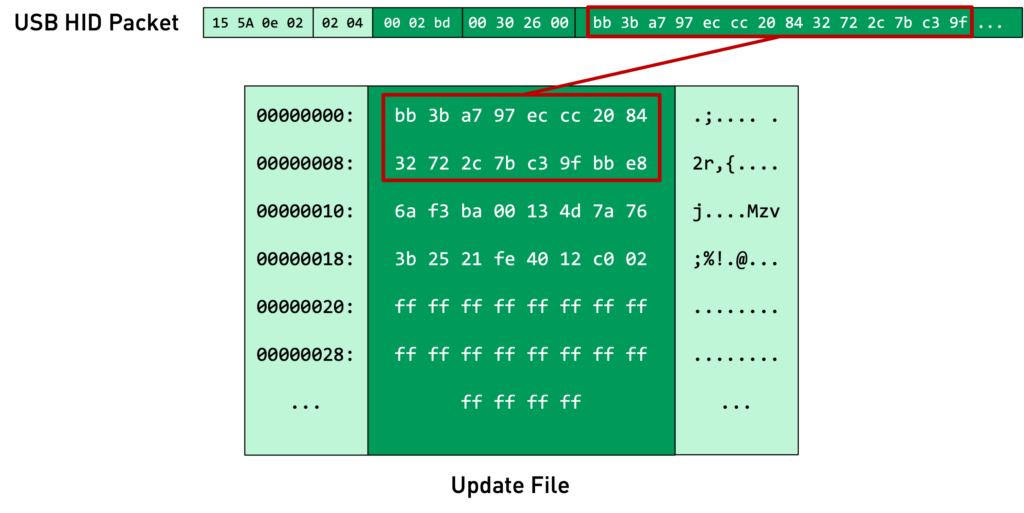

During a firmware update we noticed there were a lot of messages with the same structure. The beginning of the packets were mostly the same (15 5A 0e 02 02 04), then there was an incremental value (e.g., 00 30 26 00 or 0x263000 in little endian) followed by a larger binary blob.

It turns out the larger blobs were incremental parts of the firmware update file! The rest, we assumed, is the protocol message, and the incremental part might be the address the file is written to.

At this point, we were hooked and wanted to learn more about the protocol. Fortunately, someone already built the airoha-firmware-parser, a tool to unpack these Airoha firmware update files, also called FOTA images. This allowed us to start reverse-engineering the firmware.

After digging through the firmware and various mobile companion apps for different headphone models, we found that the name of the protocol is RACE.

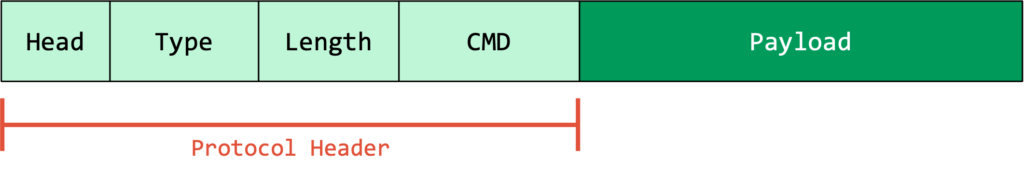

Packet Structure

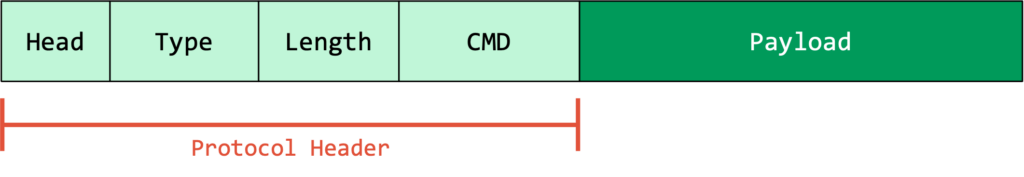

The RACE protocol is encapsulated differently depending on the transport but the core packet structure remains consistent. The payload differs drastically depending on the command. The general packet structure is depicted below:

Every RACE packet begins with a 6-byte header followed by a variable-length payload:

| Field | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Head | 1 Byte | Typically 0x05 for standard commands, 0x15 for firmware updates. |

| Type | 1 Byte | 0x5A for Request, 0x5B for Response. |

| Length | 2 Bytes | The length of the subsequent data payload. |

| CMD | 2 Bytes | The Command ID determining the operation. |

RACE Commands

We found that there a many different RACE commands, so we didn’t have time to look at and reverse engineer all of them. However, we identified a few that are relevant with regard to security. Many other commands handle things like configuring the ANC (Active Noise Cancellation), or configuring audio properties.

The four command types we are going to explain in more details are the following:

- Get Build Version (

0x1E08): Returns the SoC model, SDK version, and build time stamp. This is excellent for fingerprinting. - Read Flash (

0x0403): Allows reading pages from the flash memory. The arguments typically include a storage type, size (in pages, not bytes), and a 4-byte address. - Read/Write RAM (

0x1680/0x1681): Provides arbitrary read/write access to the entire memory map, including memory-mapped I/O (MMIO) registers and RAM. - Get BD_ADDR (

0x0CD5): Retrieves the device’s public Bluetooth Classic address. This is relevant for some of our proof of concepts, but also interesting with regard to privacy.

Transports

RACE is multiplexed across multiple interfaces. We initially found it over a USB HID connection. Then we found it is also available via BLE and Bluetooth Classic.

- USB HID: Uses Report IDs

0x06(Host to Device) and0x07(Device to Host). - Bluetooth Classic (RFCOMM): Exposed via a specific RFCOMM channel (often channel 21). We identified several vendor-specific UUIDs targeting this service:

- Default:

00000000-0000-0000-0099-AABBCCDDEEFF - Sony:

8901DFA8-5C7E-4D8F-9F0C-C2B70683F5F0 - Bose:

2D064AA9-32B5-4970-865C-643742BD2862

- Default:

- Bluetooth Low Energy (GATT): Exposed via a specific GATT service. Commands are written to the TX characteristic, and responses are received via the RX characteristic. Here we only found one vendor-specific for Sony. The other devices use the default UUID.

- Default:

5052494D-2DAB-0341-6972-6F6861424C45. - Sony:

dc405470-a351-4a59-97d8-2e2e3b207fbb.

- Default:

Visiting our Bluetooth stack image from above, the RACE protocol sits either on top of GATT, when the BLE transport is used, or on top of RFCOMM, when Bluetooth Classic is used.

Not every device we saw exposed RACE over all these transports. However, this is likely because the interface itself was not exposed. For example, the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds or the Jabra Elite 8 Active do not seem to have BLE enabled, which effectively means that GATT is not available. Most of the headphone models do not have a USB interface, or only expose it for charging, which eliminates this transport.

Impact

The later parts of this chapter will discuss the impact from a headphone user’s perspective in more detail. First we want to recap which vulnerability attackers can use as leverage for which capabilities.

1. CVE-2025-20700: Missing Authentication for GATT (BLE)

An attacker can discover and connect to headphones in proximity via BLE, e.g., on a train or in a café. Connection establishment usually happens silently without the user noticing. The lack of authentication provides covert access to the RACE protocol but does not provide any meaningful access if RACE is out of the picture.

2. CVE-2025-20701: Missing Authentication for Bluetooth Classic (BR/EDR)

Similar to the BLE flaw, this allows unauthorized connections. While Bluetooth Classic connections are sometimes more visible (and might interrupt audio streams), this vector is interesting even without the RACE protocol, as the attacker can still establish two-way audio connections to the headphones or use any other Bluetooth profile the headphones expose.

3. CVE-2025-20702: Critical Capabilities in Custom Protocol

The RACE protocol itself, accessed with or without relying on the previous two CVEs provides powerful commands intended for factory debugging. It allows reading and writing to the device’s Flash memory and RAM. It is therefore possible to permanently alter devices and extract sensitive configuration data.

Attacking the Headphones

To compromise a pair of headphones, an attacker first needs to connect to them. Taking advantage of CVE-2025-20700, for the initial connection is considerably easier than using CVE-2025-20701. The reason for this is the fact that headphones typically advertise their presence via BLE. Anyone in range can scan for BLE devices, connect to them and use the appropriate GATT service to speak the RACE protocol. In contrast, devices will not typically announce their presence or respond to inquires on Bluetooth Classic, except when they are explicitly set to discoverable or in pairing mode. To establish a connection the device’s Bluetooth Classic address has to be known. Finding the address of headphones in proximity to the attacker requires special purpose hardware (such as the Ubertooth One). It is however worth noting, that for many affected devices the Bluetooth Classic address can be inquired via RACE. This means attackers that want to establish a Bluetooth Classic connection can simply connect via BLE first and use RACE to find out the Classic address.

Eavesdropping

Using Bluetooth Classic and the Bluetooth Hands-Free Profile (HfP) attackers can use the headphone’s microphone. This is a direct consequence of the broken or missing authentication and does not rely on the RACE protocol’s capabilities. As noted earlier, establishing a Bluetooth Classic audio connection usually disrupts any pre-existing connection. In case the victim is actively listening to audio they will notice that something is happening to their headphones.

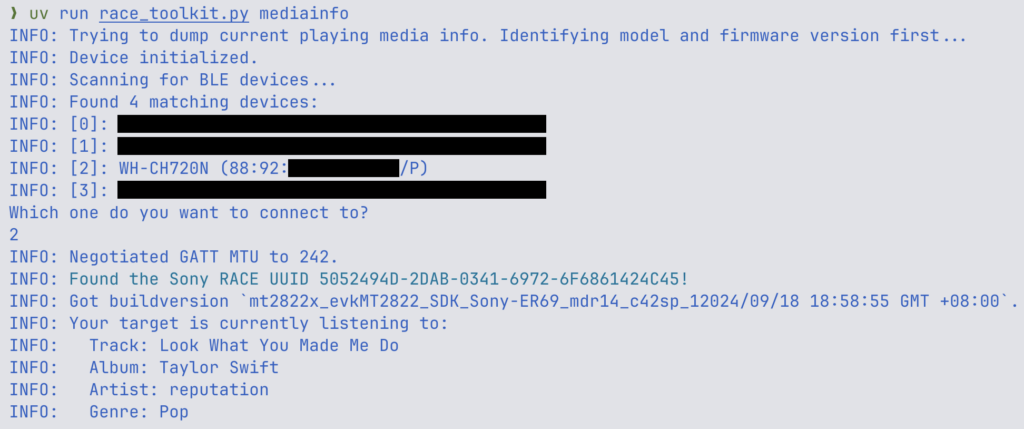

As mentioned earlier, volatile (RAM) and non-volatile (flash) storage can be read using RACE. Reading RAM allows an attacker to extract runtime information with different sensitive nature. As a proof of concept, we demonstrated that we can read out metadata related to the currently playing media. This means we can find out what the user is currently listening to.

Access to flash data allows extracting the firmware and any other data stored on the flash. This includes information on the devices the headphones have been paired with. This is an important prerequisite for other attacks, that will be discussed in the next section.

Arbitrary Code Execution

Writing to RAM or flash sections that hold executable code permits attackers to run any custom code on the device. Temporarily injecting code into RAM is of questionable use, considering the capabilities attackers have even without doing that.

Permanently infecting headphones by writing code to their flash could however be interesting to attackers. However, this process is much more complex. The flash write command restricts the areas that can be written to. In fact, this restricted area is part of the firmware update process. We can only write to the firmware update partition. Then the update process has to be triggered. This requires the ability to create a valid firmware image. However, with the given flash read capabilities, the required symmetric keys can be read and used to encrypt a firmware image. In practice, this process takes some time. Depending on the size of the firmware image, we observed that flashing the image via RFCOMM takes about 3 to 5 minutes. Via GATT the same process likely takes even longer.

Attacking the Phone

Up to this point, the damage is confined to the headphones themselves. That is already undesirable, but it gets worse once a more interesting target, such as the user’s phone gets involved. When the three vulnerabilities are chained together, the impact can be shifted from “hacking headphones” to “compromising the phone.”

To carry out the attack the following steps have to be performed:

Step 1: Connect (CVE-20700/20701) The attacker is in physical proximity and silently connects to a pair of headphones via BLE or Classic Bluetooth.

Step 2: Exfiltrate (CVE-20702) Using the unauthenticated connection, the attacker uses the RACE protocol to (partially) dump the flash memory of the headphones.

Step 3: Extract Inside that memory dump resides a connection table. This table includes the names and addresses of paired devices. More importantly, it also contains the Bluetooth Link Key. This is the cryptographic secret that a phone and headphones use to recognize and trust each other.

Note: Once the attacker has this key, they no longer need access to the headphones.

Step 4: Impersonate The attacker’s device now connects to the targets phone, pretending to be the trusted headphones. This involves spoofing the headphones Bluetooth address and using the extracted link-key.

Once connected to the phone the attacker can proceed to interact with it from the privileged position of a trusted peripheral.

Many of the proof of concepts that are targeted at the phone require a proper implementation of Bluetooth profiles, such as the Hands-Free Profile. For these attacks, the tooling was based on BTstack, which is a great implementation of the Bluetooth host stack 2.

Using HfP commands, the attacker can access different types of information. Some are restricted by the permissions the user gave during initial pairing to the headphones, some are always available.

Using the HfP AT+CNUM, the attacker can obtain the victim’s phone number. If access to the phone book was granted during initial pairing, the attacker can also access contact lists and call history.

The following screenshot shows the output of a tool based on the btstack HfP example. A connection to a victim phone is established and the AT+CNUM command is sent. The device responds with the phone number.

Remote Control

Using the HfP AT+BVRA command, the attacker can trigger voice assistants (e.g., Siri or Google Assistant). Depending on the settings on the phone, this can be used to send text messages, make calls, or perform other actions on the phone.

On iOS, Siri is enabled on the lock screen by default. However, in the locked state the possible actions that can be performed are restricted. It is possible to send text messages or make calls. Other information, such as location information, or access to notes is not possible while the phone is locked.

Hijacking Calls

Using the calling features of the Hands-Free Protocol, an attacker can make calls or accept calls. HfP also offer various other possible actions on phone calls, such as merging calls, holding calls, or obtaining the call status.

This allows an attacker to silently accept a call and receive the audio stream of the call. Alternatively, an attacker could call expensive premium numbers to cause financial damage.

Eavesdropping

In addition to the previous attacks, the phone capabilities also allow for eavesdropping. The attacker can trigger a call to an attacker-controlled phone and phone number. Once the call is established, the Bluetooth audio connection is dropped.

In consequence there will be an active phone call to the attacker using the victim phone’s internal microphone.

Proof of Concept

At 39c3 we will show how these capabilities can be used to take over the victim’s WhatsApp and Amazon accounts. Once the video is uploaded we will link it here with the correct time code for the demonstration.

If you would like to check whether your device is still affected, you can check chapter 6 of our white paper that we released alongside this blog post.

Vulnerable Devices

During this research we conducted a survey to identify what devices are affected by the vulnerabilities. In a first instance, this requires identifying devices with Airoha Bluetooth SoCs. This is a task that can be done by passive reconnaissance. For example, by examining FCC reports which usually contain photographs of the PCBs inside the device. In such cases, it might be possible to identify the SoC. Other sources can be tear-down or disassembly blogs. One notable example is the blog 52audio.com, which provides high-resolution tear-down pictures of many audio devices. Searching for Airoha SoCs on their page revealed many potential candidates for the vulnerabilities. Lastly, Bluetooth SIG members have the possibility to search for devices with specific Bluetooth SoCs. However, as non-members, this search was not available to us.

Once potential devices are identified, the more difficult step is to confirm whether they are in fact vulnerable. For this purpose, we acquired several devices. However, it was not possible for us to buy all potential devices. As such, only a subset of devices could be confirmed to be affected.

During our survey, some Airoha-based devices that were not vulnerable to the Bluetooth Classic vulnerability (CVE-2025-20701) were found. A notable example here are the Jabra Elite 8 Active earbuds. The assumption is that these vendors adapted the SDK code to enforce pairing, or changed default configurations of the SDK to secure the device. For some models we found that the pairing was unreliable. Sometimes, the device did not accept HfP or RACE connections without prior pairing, sometimes it did. An example for such a device are the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds.

Not every device exposed RACE over all described transports. However, this is likely because the interface itself was not exposed. For example, the Bose QuietComfort Earbuds or the Jabra Elite 8 Active do not seem to have BLE enabled, which effectively means that GATT is not available.

In the initial partial disclosure the following list of vulnerable devices was published. This list is not a complete list of affected devices. It only includes devices that we managed to verify. For this purpose, we acquired some of the devices, or asked colleagues and friends whether we could check their devices. For some devices, it was only possible to verify the vulnerability via BLE, as this check can be conducted with a smartphone and does not necessarily require a computer.

- Beyerdynamic Amiron 300

- Bose QuietComfort Earbuds3

- EarisMax Bluetooth Auracast Sender

- Jabra Elite 8 Active4

- JBL Endurance Race 2

- JBL Live Buds 3

- Jlab Epic Air Sport ANC

- Marshall ACTON III

- Marshall MAJOR V

- Marshall MINOR IV

- Marshall MOTIF II

- Marshall STANMORE III

- Marshall WOBURN III

- MoerLabs EchoBeatz

- Sony Link Buds S

- Sony ULT Wear

- Sony WF-1000XM3

- Sony WF-1000XM4

- Sony WF-1000XM5

- Sony WF-C500

- Sony WF-C510-GFP

- Sony WH-1000XM4

- Sony WH-1000XM5

- Sony WH-1000XM6

- Sony WH-CH520

- Sony WH-CH720N

- Sony WH-XB910N

- Sony WI-C100

- Teufel Tatws2

Due to the sheer amount of devices that are potentially still affected, there is no proper overview over the current status of fixes

There a few vendors that mention in firmware updates that the issues are fixed. Other vendors might have silently patched, some might not have patched the vulnerability at all. A positive examples is Jabra, who mentioned the CVEs in firmware release notes as well as their security center overview. Which is interesting, because they are less affected than some other vendors due to additional security measures. Moreover, they list all devices that are affected, not just the one device that were initially reported.

Below is a short list of vendor security updates that are known to us:

This large field of unclear information is another motivation for publicly disclosing the technical details. They should empower users to check their own devices. The initial plan was to create and maintain a list of devices. However, acquiring, updating, and testing all these devices would take up time and resources. In the end, it’s the manufacturers’ responsibility to patch and inform their users.

Mitigation

Users

The most important advice for users is obviously to update their devices. However, an update might not be available or the vendor might not have released information about whether the vulnerabilities were addressed in an update.

If you are a high-value target, such as a journalist, diplomat, politician, or any other person threatened by surveillance we generally recommend using wired headphones instead of Bluetooth headphones.

Also, check the list of paired devices on your phone. If there are a lot of old, unused ones, remove them. That’s one less Link Key that is potentially stolen.

Manufacturers

Manufacturers should apply the Airoha SDK patches as soon as possible. Ideally, this should have happened as soon as Airoha released the SDK update with the information about the vulnerability.

Moreover, we recommend manufacturers to do security assessments before they release their products. Following Bluetooth security testing methodology, such as BSAM could have caught these issues.

The Vulnerabilities Themselves

Very simplified and summarized, the vulnerabilities can be considered as missing authentication and exposed debug functionality.

1. CVE-2025-20700: Missing Authentication for GATT (BLE)

The GATT service should not be available to unpaired devices. GATT offers the functionality to require authentication for characteristics. There are other characteristics and services that are required to be available without pairing (e.g., the Google Fast Pair services), so a service-based authentication for GATT is sensible.

2. CVE-2025-20701: Missing Authentication for Bluetooth Classic (BR/EDR)

An unauthenticated Bluetooth Classic connection should never be possible. The device should only accept new connections when it is set in pairing mode.

3. CVE-2025-20702: Critical Capabilities in Custom Protocol

The RACE protocol should not expose critical functionality, such as reading and writing RAM or flash.

Disclosure Timeline

Below is the detailed disclosure timeline. We want to emphasize that, once the technical Email related issues were fixed, the communication with Airoha was very positive. Airoha was committed to fix the issues and provide their customers with an updated SDK quickly. We also contacted three manufacturers. Sony and Marshall did not respond to our Emails. Sony only started to respond to our inquiries once they learned that a public partial disclosure and presentation of the vulnerabilities was planned at the Troopers conference. Beyerdynamic, driven by the upcoming EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), responded to our Emails which lead to multiple positive exchanges between ERNW and Beyerdynamic.

Sony offers a bug bounty program via HackerOne. However, it was not possible to submit the issue via the platform. The terms and conditions that are required by the program are not suitable for this vulnerability. ERNW would renounce all rights to the vulnerability. As such, we would not have been allowed to share the vulnerability with Airoha or other manufacturers. Moreover, all rights to disclose details would be taken away from us.

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| March 25, 2025 | Initial notification and report to [email protected]. Start of 90-day disclosure period. |

| March 26, 2025 | ERNW provides detailed vulnerability report to Airoha. |

| March 31, 2025 | ERNW polls Airoha via another Email. |

| April 07, 2025 | ERNW polls Airoha via Email and website contact form. |

| April 14, 2025 | ERNW polls Airoha via another Email and announces that it will contact the BSI and some of the vendors by April 17 3pm German time. |

| April 24, 2025 | ERNW contacts Sony ([email protected]), Marshall ([email protected]), Beyerdynamic ([email protected]) via Email (one week later than announced). |

| April 24, 2025 | Marshall: Automatic response to confirm reception of Email. |

| April 28, 2025 | Beyerdynamic: Compliance Manager responds with request for call. |

| April 30, 2025 | Beyerdynamic: Call with short summary of the vulnerabilities and coordination of further process. |

| May 05, 2025 | Marshall: ERNW polls. Automatic response received. |

| May 07, 2025 | Beyerdynamic: ERNW sends detailed report with vendor-specific PoCs. |

| May 08, 2025 | Beyerdynamic: Confirms reception of report and asks for meeting. |

| May 09, 2025 | Airoha: ERNW polls Airoha via Email. |

| May 09, 2025 | Sony: Polling Sony via various Email addresses with explanation why HackerOne is not possible. |

| May 09, 2025 | Sony: Mail to [email protected] due to potential privacy issues with reference to EU CRA. |

| May 12, 2025 | Sony: Private contact to Sony tries to find out what Email we can contact. |

| May 13, 2025 | Sony: Email to [email protected] |

| May 16, 2025 | Sony: Response from [email protected]. Request to accept terms that turned out to be the same ones as HackeOne. ERNW responds that this is not possible due to multi-vendor disclosure and asks on how to proceed. |

| May 16, 2025 | Marshall: ERNW polls. Automatic response received. |

| May 16, 2025 | Airoha: ERNW polls Airoha via Email. |

| May 21, 2025 | Beyerdynamic: Meeting to discuss findings. |

| May 27, 2025 | Airoha: First response to ERNW. Communication begins, Airoha is very committed to handling the situation well. |

| June 04, 2025 | Airoha: Supplies vendors an SDK update with mitigations. |

| June 26, 2025 | Partial Disclosure of the vulnerabilities by ERNW via a blog post and presentation at Troopers. |

| Dec 27, 2025 | Full Disclosure of the vulnerabilities by ERNW at 39c3. |

Cheers,

Dennis and Frieder

If you like to read more about Bluetooth security, you might be interested in the following posts:

- CVE-2020-0022 an Android 8.0-9.0 Bluetooth Zero-Click RCE – BlueFrag

- Change Your BLE Passkey Like You Change Your Underwear

- Part I: Bluetooth Auracast from a Security Researcher’s Perspective

- Using the Raspberry Pi Pico W as a Bluetooth Dongle

If you’re interested in Bluetooth security assessments or IoT and embedded security assessments in general, feel free to contact us.

Since a number of people reached out to us: the registration for TROOPERS26 is already active. The CfP and CfT will open very soon; stay tuned and prepare your submissions!

-

Yes, technically GATT can also be used via Classic. And L2CAP is slightly different between Classic and BLE. This diagram is heavily simplified, but for the purpose of this blog post this depiction is fine. I think.↩︎

-

This is probably the only project where you can run

git clone && make, and it just works. Exactly what we needed here. If you ever need a Bluetooth host stack, we can really recommend BTstack!↩︎ -

No GATT exposed. Classic pairing vulnerable, but unreliably.↩︎

-

No GATT exposed, Classic pairing is enforced, not vulnerable.↩︎