Abusing Windows, politely

Intro

Unless I am blind; there does not seem to be much out there (POC’s etc) relating to the discovery made by CrowdStrike researchers, called Vectored Exception Handling Squared, or VEH². I want to say though, I do think it’s really cool that CrowdStrike published this research - I would love to see more like this! My personal mantra for what I do is: from offense comes better, deeper, defence.

CrowdStrike:

Their research begins in a common place of abuse for malware, a place where malware can intercept certain

system calls a process may make when it is hunting for indicators of compromise. For example when malware tries to disable

AMSI scanning through the patching of amsi.dll. The act of doing this is tracked by MITRE

as T1562.001, Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools.

In this blog post we will look at implementing the Vectored Exception Handling Squared technique in Rust!

This is for understanding exception mechanics and detection surface; don’t deploy on systems you don’t own/have permission to test.

Theres no place like home

To start at the beginning - for some time now malware has used direct patching to evade AMSI - this is patching the address in

amsi.dll (the AmsiScanBuffer function) with a return instruction; meaning when AMSI loads in the malware process to scan

some region of memory, the actual scan function wont run and it will just return out. In fact, I made

a blog post about this before, but with the Events Tracing for Windows stub, as opposed

to AMSI, but the concept is the same.

The problem with this, is its not particularly stealthy for an EDR or AV to pick up on. In fact, as you can see in my post here, my EDR, Sanctum, can detect NTDLL tampering.

Enter stage right Vectored Exception Handling

Vectored Exception Handling (VEH) was introduced as an alternative way to ‘hook’ or prevent certain routines in memory from being dispatched, which provides a mechanism such that you do not have to overwrite machine code in a loaded module (which can be detected through hash changes etc, as I did with Sanctum).

VEH are a feature on Windows which allow software developers to register ‘callbacks’ (or.. handlers) when an exception occurs. An example of this would be dereferencing a null pointer, take the below (rust) for example:

fn main() {

// A pointer to a u8 that itself is null

let a: *mut u8 = null_mut();

// Deref the null pointer

unsafe { *a += 1 }

}

In our program, this will generate an exception, either (if the compiler / LLVM is smart) a ILLEGAL_INSTRUCTION, or more classically, an ACCESS_VIOLATION.

Using VEH allows the programmer to create a callback for the process which says: “Anytime an exception occurs, run this code to see if we can handle it in some special way”. This allows the developer to introspectively look at things such as register states and what is on the stack. Quite helpful really.

We can add a VEH quite simply thanks to AddVectoredExceptionHandler from kernel32.dll.

These exist as an ordered handler list which the program can traverse to find an appropriate handler; allowing developers a little flexibility when it comes to dealing with exceptions.

Hardware breakpoints are a feature of the CPU which use a number of special registers to trap access to things such as memory addresses,

meaning if the CPU accesses an address you wish to monitor, it will raise an exception. This is raised as EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP.

Security researchers / malware devs realised this raises an interesting opportunity. Take for example, a process dispatching the AmsiScanBuffer function which uses AMSI to scan memory for IOCs, the malware developer can use a hardware breakpoint to raise an exception when the start of that function is accessed by the CPU.

Hopefully if you follow; you should now see that a hardware breakpoint allows us to raise an exception which we can then receive an immediate callback for - and this isn’t simply a callback that runs parallel, code execution goes to the handler before the program continues.

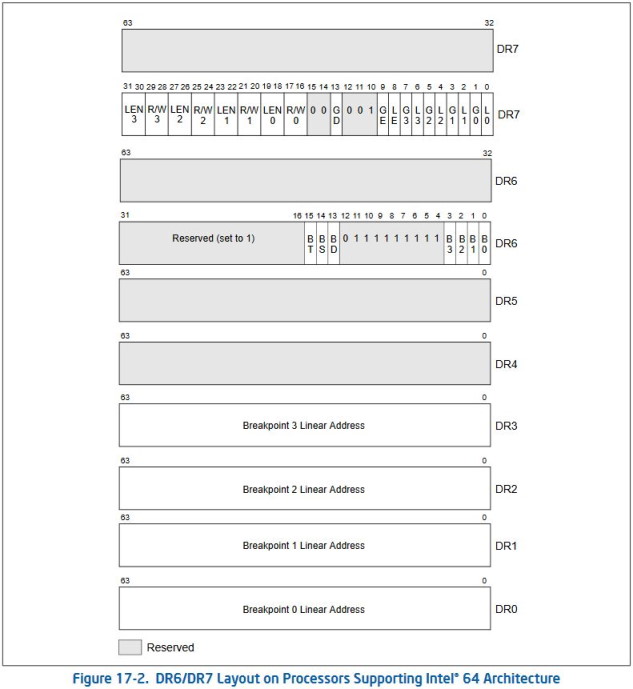

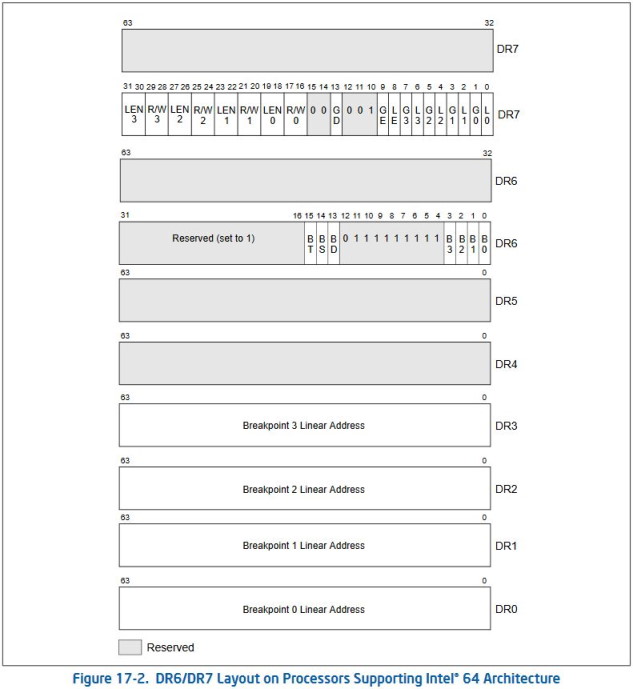

The below image taken from the intel handbook, shows the layout of the 8 debug registers.

DR0 - Dr3 are designed to contain the addresses of the breakpoint - i.e. when an address we wish to monitor (such as AmsiScanBuffer) is placed in one of these fields, on access, the program will raise the EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP exception.

Dr6 indicates which debug condition fired; for example, bit 0 (B0) is set when Dr0 triggers.

Dr7, or the Debug Control Register, is a bitmap, where essentially the lower 8 bits determine whether the breakpoint is turned on. The

even bits represent local breakpoints, and the odd bits represent the breakpoint being enabled globally. So bit 0 in Dr7 = Dr0 locally enabled.

The remaining bits in DR7 configure breakpoint type (execute / read / write) and size.

Thus, to enable Dr0, we would want the lower 8 bits of Dr7 to be: 00000001.

Its a trap

From the exception handler, we receive a CONTEXT, which

as you can see contains fields for things such as CPU registers (rax, rsp, rip, etc), but also includes the special debug registers

Dr0 - Dr7. These are not readonly fields; this gives us volatile access to the actual registers.

Thus, you can manipulate the registers, such as:

- rax: To spoof a return value.

- rip: To redirect the flow of execution.

- rsp: To manipulate the stack, to keep everything aligned as if it were a ret.

Hopefully you can see, we can manipulate these to prevent the CPU from executing a function where we manage to insert a hardware breakpoint for.

Problem

So, this is where CrowdStrike come in with their research. In normal malware abuse of VEH, they would have to register the hardware breakpoints for each thread by calling GetThreadContext and SetThreadContext. Naturally, this is an easy place for an EDR to intercept to look for signs of badness.

As the CrowdStrike blog points out - calling SetThreadContext transitions to NtSetContextThread in the kernel, and this makes a call

through to EtwWrite, which logs to the Microsoft-Windows-Kernel-Audit-API-Calls provider. So clearly, EDR solutions have various

ways of detecting the VEH hooking of sensitive APIs malware devs want to avoid triggering.

VEH Squared

The CrowdStrike researcher who was looking at this problem came up with this excellent technique, VEH², which silently

registers a hardware breakpoint without having to go through SetThreadContext.

How do we do this? Well.. as we looked at above when we handle an interrupt, we get access to the CONTEXT struct, which gives us access to the CPU’s volatile registers, including those responsible for hardware breakpoints!

So the strategy:

- Register a Vectored Exception Handler.

- Trigger an exception, the most reliable way to do this would be through triggering a EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT via the int3 assembly instruction.

- In the VEH, when triggered from our code, modify the CONTEXT to set a hardware breakpoint to monitor access to the function pointer for AmsiScanBuffer (i.e. the first instruction of that function).

- Have a specific code path within the VEH which checks for the enum which represents a EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP, which:

- Modifies rax to be the result AMSI_RESULT_CLEAN.

- Retrieves the value at the stack pointer (rsp) and puts this into the instruction pointer (this is the return address from the function once it is complete).

- Add 8 to rsp; simulating the ret instruction behaviour (i.e. popping the return address from the top of the stack).

I have drawn this to help visualise what is going on:

When writing the initial VEH, we need to work out how to continue execution as if nothing happened. In the above steps, I listed we can issue an int3 assembly instruction to trigger an exception. When we handle this in the VEH, we need to continue executing our program. Well, how do we do that? We are currently in a bit of a bear cave!!

We need to take the rip where the breakpoint occurred and increment this by the length of the faulting instruction(s) such that

the program can resume from that point.

Compiling rust directly with rustc, we can output the compiled assembly via:

cargo rustc --release -- --emit=asm -C llvm-args=--x86-asm-syntax=intel

And then read it into an obj dump file with the command:

llvm-objdump -d --x86-asm-syntax=intel target\release\veh.exe > f

If we open the (sloppily named) file, f, and we look for the size of an int3 instruction, we can see it is only 1 byte long, of 0xcc:

0000000140001000 <.text>:

140001000: 48 83 ec 28 sub rsp, 0x28

140001004: ff d1 call rcx

14000100c: cc int3 # *** this is what we are looking for

Let’s now presume we were dealing with the below fault:

1400010f7: 66 0f 1f 84 00 00 00 00 00 nop word ptr [rax + rax]

140001100: c6 00 01 mov byte ptr [rax], 1 # faults if RAX=0

140001103: 55 push rbp

Assuming we are dereferencing a null pointer (rax=0) at address 0x140001100 - this will produce an access violation. If we wanted to use this to trigger the initial exception, then you would want to continue execution from the rest of the valid program, i.e. from address 0x140001103, so you would need to increment rip by 3, such that it will resume from 0x140001103.

I would add, it is dangerous to be resuming from ACCESS_VIOLATIONs unless you know it occurred at a purposeful place you did this to trigger such a violation - doing so randomly will almost certainly produce horrendous side effects in the host process.

If you don’t redirect rip away from the breakpoint address (or temporarily disable it), you can end up re-triggering the exception immediately and entering a never ending loop…

A caveat

Note that this needs to be applied per thread - however (as CS point out), AMSI scanning is performed within the same thread loading the .NET assembly - so for AMSI patching, we gucci. I also expect, if malware is mostly single threaded, using this technique to also prevent Events Tracing for Windows (in usermode) triggering, this would be acceptable. CS do note that COM usage often involves the generation of several threads; so another caveat to consider.

POC

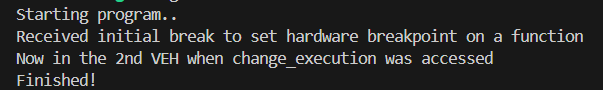

So, to showcase a proof of concept; if successful the program will not print: If this worked I should not print!!!! :( because we prevented the function from ever executing. To showcase the result up front:

Success!

The POC, you can find this on my GitHub:

use std::ffi::c_void;

use windows_sys::Win32::{Foundation::{EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT, EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP, STATUS_SUCCESS}, System::Diagnostics::Debug::{

AddVectoredExceptionHandler, CONTEXT_DEBUG_REGISTERS_AMD64, EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION, EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH, EXCEPTION_POINTERS

}};

fn main() {

println!("Starting program..");

let _h = unsafe { AddVectoredExceptionHandler(1, Some(veh)) };

unsafe { core::arch::asm!("int3") };

change_execution();

println!("Finished!")

}

#[inline(never)]

fn change_execution() {

println!("If this worked I should not print!!!! :(");

}

unsafe extern "system" fn veh(p_ep: *mut EXCEPTION_POINTERS) -> i32 {

let exception_record = unsafe { *(*p_ep).ExceptionRecord };

let ctx = unsafe { &mut *(*p_ep).ContextRecord };

if exception_record.ExceptionCode == EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT {

println!("Received initial break to set hardware breakpoint on a function");

// Set the address we wish to monitor for a hardware breakpoint

ctx.Dr0 = change_execution as *const c_void as u64;

// Set the bit which says Dr0 is enabled locally

ctx.Dr7 |= 1;

// Increase the instruction pointer by 1, so we effectively move to the next instruction after int3

ctx.Rip += 1;

// Set flags

ctx.ContextFlags |= CONTEXT_DEBUG_REGISTERS_AMD64;

ctx.Dr6 = 0;

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

} else if exception_record.ExceptionCode == EXCEPTION_SINGLE_STEP {

// Gate the exception to make sure it was our entry which triggered

// to prevent false positives (will probably lead to UB in the process)

if (ctx.Dr6 & 0x1) == 0 {

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH;

}

println!("Now in the 2nd VEH when change_execution was accessed");

// fake a return value as if we intercepted a syscall

ctx.Rax = STATUS_SUCCESS as u64;

// get return addr from the stack

let rsp = ctx.Rsp as *const u64;

let return_address = unsafe { *rsp };

// set it

ctx.Rip = return_address;

// simulate popping the ret from the stack

ctx.Rsp += 8;

ctx.Dr6 = 0;

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

}

EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH

}

Detection opportunity

Of course, as with everything in the cat and mouse game of cyber, there will be detection opportunity with this - perhaps in memory scanning of VEH and the debug registers (perhaps from kernel mode, or even usermode). Thus, when thinking about using this on red team engagements, consider your ‘offense in depth’ threat model of your target. Test on EDR’s you are going to face, and limit this to only been used when needed. Consider removing the handler after the dotnet assembly has finished executing.

Happy hacking!