嗯,用户让我总结一下这篇文章的内容,控制在100字以内,而且不需要特定的开头。首先,我得通读文章,抓住主要观点。 文章讲的是使用seccomp用户通知来进行进程注入。这是一种新的技术,之前没怎么被记录过。它的好处是可以在父进程到子进程之间注入共享库,不需要LD_*环境变量或特权能力,不管ptrace_scope配置如何。 然后,文章提到了seccomp用户通知的限制,比如只能在父进程创建子进程时使用,注入的代码权限和目标进程一样。还有需要目标程序是动态链接的。 接着比较了其他注入技术,比如ptrace、procfs、process_vm_writev等,并讨论了它们在不同ptrace_scope下的限制。 最后,作者展示了如何利用seccomp通知来注入共享库,并提供了一个PoC代码。结论是这种方法在受限系统上可能更有效。 现在要总结这些内容到100字以内。需要涵盖技术名称、优势、限制、比较的技术以及结论部分。 可能会这样组织:介绍技术名称和优势,然后提到限制和适用条件,最后比较其他方法并说明其优势。 </think> 文章介绍了一种基于seccomp用户通知的Linux进程注入技术,允许父进程向子进程注入共享库而无需特权或LD_*环境变量。该方法通过劫持openat系统调用来实现动态链接器加载恶意库,并利用IFUNC解析器在符号解析前执行代码。此技术绕过了Yama LSM的ptrace_scope限制,并适用于动态链接的目标程序。 2025-12-9 18:5:10 Author: www.outflank.nl(查看原文) 阅读量:6 收藏

This post demonstrates the use of seccomp user notifications to inject a shared library into a Linux process. I haven’t seen this combination documented as a process injection technique before, and it has some benefits over alternatives. In summary, seccomp user notifications enable user-space injection from parent to child without any LD_* environment variables or privileged capabilities, regardless of the ptrace_scope configuration. However, seccomp user notifications have some notable limitations:

- Seccomp user notifications were introduced in Linux kernel version 5.0, but this PoC relies on

SECCOMP_ADDFD_FLAG_SEND(Linux 5.14+) to avoid TOCTOU issues when hookingopenat. - Requires you to create the target process (parent-to-child injection only).

- The injected code runs with the same UID, namespaces, and LSM label as the target process. This technique doesn’t bypass normal privileged boundaries.

My specific implementation also requires the target executable to be dynamically linked, though there may be alternative implementations that do not.

Existing Linux Process Injection Techniques

While I don’t want to focus too much on other techniques, I will briefly describe previous research for comparison to my PoC. For a comprehensive overview of alternative injection options, I recommend Ori David‘s Linux process injection guide.

Injection into a running process typically requires (at least) one of ptrace, procfs, or process_vm_writev primitives.

- The

ptracesystem call enables a debugger to read/write memory and registers, as well as pause or single-step through the process. It also ignores the page permissions of virtual memory, which makes process injection straightforward. - Each Linux process is represented by a directory under

/proc. The process directory contains various files that include information such as environment variables and even virtual memory. By accessing these pseudo-files under/proc, a remote process can read and write the target’s virtual memory. - The

process_vm_writevsystem call is similar toWriteProcessMemoryon Windows. It allows a process to write data directly to the address space of a remote process. Unlikeptraceandprocfs,process_vm_writevrespects the target’s page protections, so you can’t directly write to read-only or read-execute memory.

On distributions that include the Yama LSM by default (e.g., most Debian and RHEL variants), all three primitives can be constrained using ptrace_scope: a system-wide value ranging from 0 to 3. The default values on many distributions, 0 or 1, allow a process to attach to any of its descendants or, if it has CAP_SYS_PTRACE, to any process. This value also affects access to /proc/<pid>/mem and the process_vm_writev syscall. Increasing the ptrace_scope value further restricts access; ptrace_scope=3 disables remote process attachment entirely.

For concrete examples of these primitives, see the companion PoC repository from Ori’s post.

Shared Library Injection

There are a couple of common ways to inject a shared library into an existing process. First, any of the techniques from the previous section could force a running process to execute dlopen. If you are creating a new process, you can also set the LD_PRELOAD environment variable. In my Linux EDR research, I observed that many products heavily instrument process creation, so I prefer to avoid LD_PRELOAD-style injection.

You can place a shared library on disk for either option, or you can create an in-memory file using memfd_create or /dev/shm. Loading a library from memory may make forensics more difficult since a memfd-backed .so doesn’t have a persistent on-disk path, though it can still be discovered via /proc/<pid>/fd and memory inspection.

Process Injection with Seccomp Notify

The primary strength of seccomp notify injection is that it enables parent-to-child injection at any ptrace_scope level, without requiring elevated privileges.

Seccomp User Notifications

Seccomp is a Linux kernel feature that restricts the system calls a process can make. It was introduced in Linux 2.6.12 for attack surface reduction, and later extended with seccomp-bpf in kernel version 3.5, which is commonly used in limited-privilege environments such as containers and web browsers.

A seccomp filter can take various actions on system calls, such as allowing the call, returning an error code, or even killing the process. Newer kernels (Linux 5.0+) support a “user-notification” action that notifies a user-mode process to inspect the system call and respond with a decision. One option allows the user-mode process to emulate the system call, enabling more complex sandboxing without kernel-mode code.

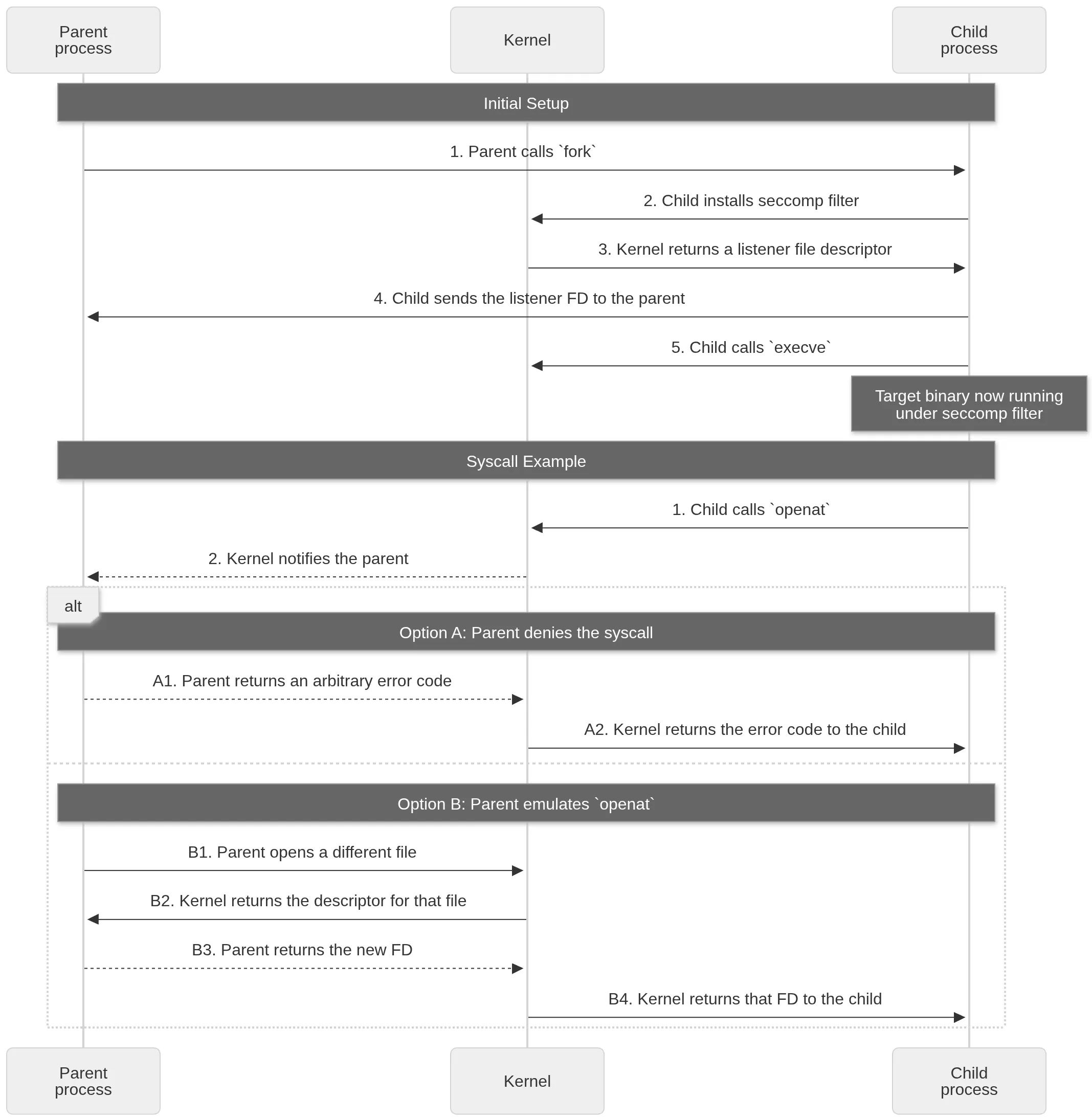

For example, consider this simplified example in which a parent process hooks the openat system call:

The initial setup only requires a few steps:

- The parent creates a new process using

fork. - Before calling

execve, the child process installs a seccomp filter usingseccomp(SECCOMP_SET_MODE_FILTER, SECCOMP_FILTER_FLAG_NEW_LISTENER, ...). - The kernel adds a BPF filter to the calling thread and returns a new “listening” file descriptor that can be used to receive notifications whenever the child makes a filtered syscall.

- The child sends this file descriptor to its parent.

- Now the child can launch a program with

execve.

Each filtered system call will follow a process like this:

- The child executes a filtered syscall:

openat. - Instead of executing

openat, the kernel notifies the parent process and waits for its response. The parent has a couple of options:- The parent can effectively block the syscall by returning an error code with

SECCOMP_IOCTL_NOTIF_SEND(id, error=-EPERM). - The parent can also effectively emulate the syscall by calling

openatitself and then returning the result withSECCOMP_IOCTL_NOTIF_ADDFD(id, srcfd=<alt_fd>, flags=SECCOMP_ADDFD_FLAG_SEND)where “<alt_fd>” is replaced with an arbitrary file descriptor.

- The parent can effectively block the syscall by returning an error code with

By default, seccomp filters are per-thread, but since the child installs a filter right after fork, no other threads should exist. Threads created later will inherit the seccomp filter as well.

For more details on seccomp user notifications, see The Seccomp Notifier – New Frontiers in Unprivileged Container Development.

Implementing Process Injection

My specific implementation is conceptually similar to LD_PRELOAD injection. However, it does not set any environment variables for the target process. This was my initial approach; since seccomp can filter many system calls, alternative implementations may differ significantly.

The proof-of-concept follows these steps to spawn a new process and inject shellcode into it:

- The injector process loads a

.soshellcode loader into memory usingmemfd_create. - The injector

forks a child process. - The child installs a seccomp filter for

openatand sends the listener FD back to the injector process. - The child executes a target binary using

execve. - The injector waits for an

openatcall and returns a file descriptor for the shellcode loader.

It should be clear from this sequence why the target process must be dynamically linked. My implementation hijacks the dynamic linker’s openat calls to make the target process load a malicious library instead.

You may have noticed an issue with this strategy: replacing a shared library during startup likely causes problems with dynamic linking. To solve this issue, I took inspiration from the 2024 XZ Utils backdoor. Similar to the infamous backdoor, my PoC uses an IFUNC resolver to execute code before normal symbol resolution. These resolvers execute during relocation, which happens early in dynamic loading. In my testing, the resolver reliably executed before normal symbol resolution, though the exact order may vary depending on how the dynamic linker processes relocations. This gives the library time to execute shellcode and block the process before it crashes.

As shown below, the PoC can spawn and inject shellcode into the memory of a process running a specified executable, regardless of the ptrace_scope value.

curlYou can find the proof-of-concept code here: https://github.com/outflanknl/seccomp-notify-injection.

Conclusion

Other Linux process injection methods can often inject into an arbitrary process, similar to Windows injection, but may be limited on hardened systems. Seccomp user notifications offer a complementary alternative with different constraints.

This technique doesn’t violate Yama’s ptrace_scope restrictions because the injector never directly interacts with another process. From the kernel’s perspective, this technique implements seccomp-notify’s intended use case: a user-space supervisor emulating syscalls for a child process. There are likely additional opportunities for abuse with seccomp user notifications, as it can easily hook any system call that returns a simple scalar value without additional memory access.

Outflank continually expands the tools and techniques available in Outflank Security Tooling (OST), a broad set of evasive tools that allow users to safely and easily perform complex tasks. This toolset includes a C2 implant for Linux operating systems. Consider scheduling an expert-led demo to learn more about the diverse offerings in OST.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh