嗯,用户让我总结一下这篇文章的内容,控制在一百个字以内,而且不需要用“文章内容总结”或者“这篇文章”这样的开头。直接写文章的描述即可。 首先,我需要通读整篇文章,理解它的主要内容。文章主要讲的是QuasarRAT,这是一种基于.NET的远程访问木马。作者详细介绍了如何从二进制文件中提取其加密配置。他们使用了Jupyter Notebook、pythonnet、dnSpy等工具来构建一个Python提取器,并且还处理了混淆版本的样本。 接下来,我需要找出文章的关键点:QuasarRAT是什么,它的功能,以及如何提取配置。还要注意作者提到的方法和工具。 然后,我要把这些关键点浓缩成一百个字以内。确保涵盖QuasarRAT作为.NET RAT的特点、提取加密配置的过程、使用的工具和方法,以及处理混淆版本的能力。 最后,检查语言是否简洁明了,符合用户的要求。 </think> 文章介绍了如何从QuasarRAT(一种基于.NET的远程访问木马)的二进制文件中提取其加密配置。通过使用Jupyter Notebook、pythonnet和dnSpy等工具构建Python提取器,并分析其静态构造函数和IL指令,成功提取了配置信息。文章还扩展了方法以处理混淆版本的样本,并展示了如何通过逆向工程恢复加密字符串。 2025-12-8 09:16:41 Author: blog.sekoia.io(查看原文) 阅读量:2 收藏

In the second part of our “Advent of Configuration Extraction” series, we unwrap QuasarRAT, a popular .NET remote access trojan (RAT), and show how to extract its encrypted configuration out of the binary. The article begins by detailing the environment: Jupyter Notebook, pythonnet, dnSpy and friends—so every step is reproducible. Next, it presents the construction of a Python-based extractor for a clean QuasarRAT sample, then extends the approach to handle an obfuscated build.

QuasarRAT is an open-source RAT that first appeared in 2014, under the name xRAT. Originally published on GitHub as a legitimate Windows remote administration tool. Over time, however, its accessibility, small size, and ease of modification have led to it being frequently abused by cybercriminals and threat actors for malicious purposes. For more information about the RAT itself, the JPCERT made a presentation at the Botconf 2020 which details the origins, variants and capabilities.

Implemented in C# on the .NET Framework, QuasarRAT lends itself readily to extension, recompilation and customisation. Its open-source codebase has been thoroughly analysed and adapted by threat actors seeking bespoke functionality.

Functionally, QuasarRAT supports a broad set of remote administration functions, including features such as system information collection, file management, remote desktop viewing, keylogging, and command execution. While these capabilities can be used for legitimate administrative tasks, they are also commonly leveraged in cyber espionage, unauthorized surveillance, and other forms of intrusion.

It has been observed in multiple attacks orchestrated by both independent threat actors and state-aligned groups. Its popularity stems from being lightweight, configurable, and freely available, making it a recurring tool in Windows-targeted malware campaigns.

DnSpy and ILSpy are widely adopted for .NET sample analysis. A Jupyter Notebook environment has been configured to support configuration extraction development, incorporating libraries for PE/ELF manipulation, decompilation frameworks, and related tasks. To facilitate the environment portability, the configuration has been containerised with Docker.

This installment of “Advent Of Configuration Extraction” focuses exclusively on the .NET decompiler component. The extractor for .NET malware configuration which must interact with the Intermediate Language (a.k.a IL) relies on a combination of pythonnet and dnlib. In this arrangement, dnlib serves as the core engine for reading, rewriting, and inspecting .NET assemblies, while pythonnet acts as a bridge that allows Python code to invoke dnlib’s APIs.

Dnlib is an open-source .NET library designed for deep inspection and modification of .NET assemblies (EXE and DLL files). It exposes metadata, types, methods, attributes, and IL instructions in a programmatic fashion, making it a powerful tool for reverse engineering and malware analysis.

import clr

clr.AddReference("System.Memory")

from System.Reflection import Assembly, MethodInfo, BindingFlags

from System import Type

DNLIB_PATH = 'https://t7f4e9n3.delivery.rocketcdn.me/workspace/utils/dnlib.dll' # path in docker to dnlib.dll

clr.AddReference(DNLIB_PATH)

import dnlib

from dnlib.DotNet import *

from dnlib.DotNet.Emit import OpCodes

module = dnlib.DotNet.ModuleDefMD.Load(MALWARE_PE_PATH)Code 1. Python prelude to load a .NET sample to interact with its namespaces, classes and methods

The preceding Python snippet uses pythonnet’s clr module to load and interact with .NET assemblies. Invoking AddReference(“System.Memory”) grants access to low-level memory handling-types. These preliminary calls are required to import the dnlib framework for the next and most required step that will load to pythonnet the dnlib framework. Once dnlib is loaded, the script can open and analyse a .NET PE or DLL, enabling it to:

- Decompile individual function.

- Traverse the assembly structure: namespace, classes, methods, and variables.

- Extract custom types, metadata entries, and embedded strings.

At this stage, the most “critical” portion of the lab setup is complete. The module variable provides programmatic access to the bulk of the decompiled .NET content.

Before proceeding with QuasarRAT configuration extraction, a brief overview of the .NET Intermediate Language is necessary.

Within the .NET decompilation context, Intermediate Language (IL) is also referred to as MicroSoft IL (MSIL) or Common IL (CIL).

IL is a stack‑based intermediate bytecode used by .NET. High-level source (C#, VB.NET, etc.) compiles into IL, which the Common Language Runtime(CLR) then JIT-compiles into native machine code.

IL is a stack machine, meaning:

- Instructions push values onto a stack.

- Other instructions pop values from the stack.

- Operations work on the stack (not registers).

Each IL instruction has:

- Opcode: The operation, e.g.

ldstr,stloc,call,add,ldc.i4. - Operand (optional): Additional data the instruction needs:

- strings

- class/method references

- integers

- branch targets

- metadata tokens

The Intermediate Language instruction are as fallow: Instruction Operand

In the extract of IL code above, there are 3 distincts instructions: ldstr, stsfld and ldc.i4.

| Instruction | Description | Example |

ldstr | Load String: Pushes a string literal onto the evaluation stack. | ldstr “Hello” push the string Hello on the stack |

stsfld | Store into Static Field: Pops a value from the evaluation stack and stores it into a static field of a class. | stsfld string Main.test.name pop the last value on the stack into Main.Test.name |

ldc.i4 | Load constant int32: pushes a 32-bit integer constant onto the evaluation stack.pushes a 32-bit integer constant onto the evaluation stack. | ldc.i4 42push the value 42 on the stack |

Table 1. Example of IL instructions

RATnip for Rookies: Unwrapping the Bare-Bones Config

As noted earlier, QuasarRAT is an open-source project. In this example, a self-compiled sample with the DEBUG disable is employed, ensuring that all settings strings remain in plain text. The configuration resides in the Config namespace, within the Settings class. That class defines the following RAT configuration keys: version, hosts, reconnectdelay, specialfolder, directory, subdirectory, installname, install, startup, mutex, startupkey, hidefile, enablelogger, encryptionkey, tag, logdirectoryname, serversignature, servercertificatestr, servercertificate, hidelogdirectory, hideinstallsubdirectory, installpath, logspath, and unattendedmode.

The extraction strategy relies on the pythonnet/dnlib stack to play with the assembly’s code structure. The extractor first iterates through all namespaces until it finds the one named Config, then scans the “Config” namespace’s classes until it reaches Settings.

For simplicity, this example focuses solely on the Command-and-Control server entry stored in the Settings class member HOSTS.

This initial task is to locate the target namespace and class, as shown below:

target_ns = "Config"

target_class = "Settings"

found_setting_class = None

for t in module.Types:

if t.Namespace.EndsWith(target_ns) and t.Name.EndsWith(target_class):

found_setting_class = t

break

if found_setting_class:

print("Class found:", found_setting_class)

else:

print("Class not found.")Code 2. Python code to identify the Settings class from the Config namespace

A glance at the class in dnSpy might suggest that iterating over Settings.Fields completes the task. In fact, this collection exposes only the field definitions (type and full name), not their actual values.

for field in found_setting_class.Fields:

print(field)Code 3. Python code to iterate over filed of a the Settings class

System.String Quasar.Client.Config.Settings::VERSION

System.String Quasar.Client.Config.Settings::HOSTS

System.Int32 Quasar.Client.Config.Settings::RECONNECTDELAY

System.Environment/SpecialFolder Quasar.Client.Config.Settings::SPECIALFOLDER

System.String Quasar.Client.Config.Settings::DIRECTORY

...Log 1. Output of the Code 3 code.

In .NET IL, static fields are initialised by the class’s static constructor, known as .cctor (standing as Class ConsTOR). Examining this initialiser in dnSpy requires switching the decompiled view from C# to IL, yielding the following output:

The extraction strategy begins by locating the Settings class’s static constructor. It then walks through each instruction alongside its predecessor in order to capture paired operation. In this case, the first instruction loads a literal string (ldstr), and the immediately following instruction references the corresponding class field.

Decompiling a method with dnlib requires a dnlib.DotNet.MethodDefMD instance. Instruction types can be detected in two ways:

- By comparing the opcode name as a string, e.g.:

instr.OpCode.Name == "ldstr". - By comparing the opcode against the

dnlib.DotNet.Emit OpCodesenum e.g.:instr.Opcode == OpCodes.Ldstr.

The direct opcode comparison is the option preferred at TDR for its clarity and consistency.

for m in found_setting_class.Methods:

prev_instr = None # Track previous instruction

if m.IsStatic and m.Name == ".cctor":

print("Analyze constructor method of the `Config.Settings` class")

# Scan the IL instructions to find the constant assignment

for instr in m.Body.Instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Stsfld and instr.Operand is not None:

field = instr.Operand

if field.Name == "HOSTS":

print(instr, prev_instr)

# Get the previous instruction that loads the constant

if prev_instr is not None:

if prev_instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldstr: # String constant

print("Get String constant", prev_instr.Operand)

prev_instr = instrCode 4. Full Python code to read the HOSTS field of the Settings class from the Config namespace

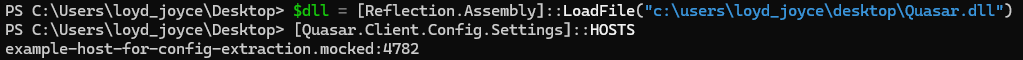

Quick tips: PowerShell’s Reflection capabilities can load a .NET assembly, then access its members or invoke its methods directly from the command line. This approach is especially useful for probing obfuscation and deobfuscation routines without a debugger.

Source: X message of @struppigel

Figure 3. Example of PowerShell Reflection capabilities with the self-compiled QuasarRAT sample

Elf-Sized Encryption: Breaking the Obfuscated QuasarRAT

The sample under analysis has the following: SHA-256: 4ef44bf6815e78603aec5b480f43fa26d883897c88ced763565e912c38ac9639

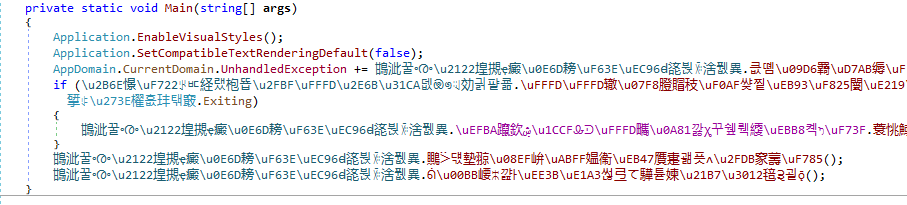

This build employs a generic .NET obfuscator, many tools are available on GitHub such as .NET-Obfuscator, obfuscar. A quick inspection in dnSpy confirms significant obfuscation.

Manual deobfuscation of each variant is impractical, so multiple extraction strategies must be explored. Since the DEBUG flag is unset, the RAT is expected to decrypt its settings at runtime.

Source code analysis indicates that QuasarRAT uses AES-256 in CBC mode, with the key derived via PBKDF2. Although, all the configuration keys remain declared in the Settings class, their actual values are assigned in the Initialize method. A closer look at the Aes256 module of the RAT reveals that it uses the default system implementation of AES implementation, and how the cryptographic material is configured.

The aes module yields important insights:

- The AES key is stored as a class member and initialised in the static constructor (c.f. .cctor method);

- A hardcoded salt value within in the aes class is required for PBKF2 key derivation;

- Encrypted strings follow a fixed layout:

Drawing on objectives and insights from the source code review, the extraction strategy to bypass obfuscation proceeds as follows:

- Locate the

Aes256class in theCrytographynamespace; - Extract the hardcoded salt field from Aes256 class;

- Resolve cross-references to Aes256 in order to pinpoint the Settings class within the Config namespace;

- Retrieve the AES key stored in the Settings;

- Enumerate all encrypted string fields in Settings;

- Decrypt each string using the derived AES key and salt.

Many of the utility routines, such as fetching a field from a type, iterating through class members, and resolving cross-references are generic and readily reusable across other .NET malware analysis.

Step 1 – Searching the Cryptography.Aes256 class

Frequent interaction with .NET samples via Python typically starts with a routine that traverses the module’s types (represented in dnlib as a ModuleDefMD).

In QuasarRAT’s Aes256 implementation, the standard .NET AES provider System.Security.Cryptography.AesCryptoServiceProvider is instantiated. To locate these instantiations, a helper function loops over each ModuleDefMD.Type, then over each MethodDef, searching for an IL instruction of the form:

Newobj System.Security.Cryptography.AesCryptoServiceProvider::.ctor()

The following snippet demonstrates this scanning approach:

def search_crypto_class():

"""This function iterate over all class and methods

of the module for the creation of the AesCryptoServiceProvider

"""

for mtype in module.GetTypes(): # iterates over each type

if not mtype.HasMethods:

continue

for method in mtype.Methods: # iterates over each method

if not method.HasBody:

continue

if not method.Body.HasInstructions:

continue

if len(method.Body.Instructions) < 20:

continue

for ptr in method.Body.Instructions: # iterate over each instruction

# Verify that a crypto provider is contructed

if (

ptr.OpCode == OpCodes.Newobj

and ptr.Operand.FullName

== "System.Void System.Security.Cryptography.AesCryptoServiceProvider::.ctor()"

):

print(

f"Crypto class found {method.FullName} in {mtype.Name}"

)

return mtypeCode 5. Python function used to locate the AesCryptoServiceProvider constructor

Step 2 – Search the salt value

Within the common.Cryptography namespace, the salt for AES key derivation is stored as a private static byte array in the Aes256 class.

Since this array is the only compile-time constant in the class, it is initialised in the static constructor (.cctor). In that method, a ldtoken instruction loads a metadata token pointing to another static class where the raw byte data resides. By resolving this token, the salt value can be extracted directly from the referenced field:

- In the

.cctorof the class there is aldtoken(Load Token) the token is defined in another static class within a structure call void <redacted path> RuntimeHelpers::InitialzeArray(<redacted>)stsfld unit8[] CryptoClass::seed_member

def search_salt(cryto_class) -> Optional[bytes]:

for m in cryto_class.Methods:

if m.IsStaticConstructor:

# the seed is always a byte array -> System.Byte[]

for instr in m.Body.Instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldtoken:

# we get the name of the static field here

init_var_name = (instr.Operand.get_Name())

# simply retrieve the structure member value

seed = get_field_from_struct(init_var_name)

if seed:

return seed

def get_field_from_struct(struct_name: str) -> Optional[bytes]:

for typeDef in self.module.Types:

for field in typeDef.Fields:

if field.Name == struct_name and field.HasFieldRVA:

return bytes(field.InitialValue)Code 6. Python code used to extract the salt bytes array used to derive the AES key

Step 3 – Cryptographic function X-Ref

At this stage, the Aes256 class is accessible, and the next goal is to locate its sole caller, namely, the Settings.Initialize method. Identification of the constructor can proceed by spotting either the Rfc2898DeriveBytes invocation (System.Security.Cryptography.Rfc2898DeriveBytes::.ctor) or the Aes256 .ctor reference directly.

def search_caller(class_name: str, method_name: str) -> Optional[Tuple[str, str]]:

# Iterate over all types in the assembly

for typeDef in self.module.Types:

for method in typeDef.Methods:

if not method.HasBody:

continue # Skip methods without a body

# Scan IL instructions for calls to A::func1

for instr in method.Body.Instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Call and instr.Operand is not None:

if (

instr.Operand.Name == method_name

and instr.Operand.DeclaringType.Name == class_name

):

return typeDef.Name, method.Name

Code 7. Python function used to search reference to a function in a program

Once the constructor method is identified, the extractor performs a cross-reference search across all namespaces, types, and methods to pinpoint its unique caller. This exhaustive traversal can be time-consuming, as it requires inspecting all the assembly.

def search_caller(class_name: str, method_name: str) -> str:

# Iterate over all types in the assembly

for typeDef in module.Types:

for method in typeDef.Methods:

if not method.HasBody:

continue # Skip methods without a body

# Scan IL instructions for calls to A::func1

for instr in method.Body.Instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Call and instr.Operand is not None:

if instr.Operand.Name == method_name and instr.Operand.DeclaringType.Name == class_name:

return typeDef.Name, method.NameCode 8. Python function used to return a handle to the specific function in a class

Step 4 – Searching for cryptographic material in Settings

At this point, the extractor re-uses the reference to the Settings class and is equipped to retrieve its configuration. The remaining steps rely primarily on Pythonic logic rather than dnlib-specific routines. In the Settings class’s initializer, the decryption routine is invoked repeatedly, a pattern leveraged by the extractor. By tallying the number of calls to each method within Settings, the routine with the highest call count can be inferred as the decryption function. Once identified, the extractor retrieves the first argument from each invocation, which corresponds to the encrypted string. On the other hand, there is a unique call to the Aes256 object construction whose unique parameter is the AES key.

P.S.: The code only needs to retrieve one parameter as the decryption function only takes the encrypted string, the AES key is stored in a member of the Aes256 instance.

def get_func_parameter(method) -> defaultdict:

"""This only work in this context of func that take only ONE parameter"""

is_call = None

callers_with_args = defaultdict(list)

# read the function instructions backward

reversed_instructions = list(method.Body.Instructions)[::-1]

for instr in reversed_instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Call:

is_call = instr.Operand

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldsfld and is_call:

callers_with_args[is_call].append(instr.Operand)

is_call = None

return callers_with_argsCode 9. Extract the first argument of a function call

def search_aes_key(mclass):

method_that_use_aes_key = None

for m in mclass.Methods:

ldsfld, calls = 0, defaultdict(int)

for instr in m.Body.Instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldsfld:

ldsfld += 1

elif instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Call:

calls[str(instr.Operand.Name)] += 1

if any(filter(lambda x: x > 2, calls.values())):

method_that_use_aes_key = m

# Here we search the function that initialize the AES key (PBKF2)

# There is only one call to this function and the only arg is the

# ref token to the AES key that is going to be derived

call_to_search = None

callers = get_func_parameter(m)

counting = [n for v in callers.values() for n in v]

values_counting = Counter(counting)

unique = {num for values in callers.values() if all(values_counting[n] == 1 for n in values) for num in values}

AES_key_variable = unique.pop()

print(f"The AES key is located in {AES_key_variable.FullName}")

aes_key = get_constant_from_class(mclass, AES_key_variable.Name)

print(f"The AES key value is: {aes_key}")

return aes_key

if method_that_use_aes_key:

breakCode 10. Python function used extract the AES key

Step 5 – Pulling obfuscated string

This routine parallels the extraction method used for the unobfuscated sample. It locates the static constructor (.cctor) of the target class and reads each field initialiser in declaration order. Since the CLR preserves the source order of static fields, the obfuscated string values emerge sequentially. Applying the previously recovered AES key, salt, and IV decrypts those strings and reveals the complete RAT configuration.

def extract_all_encrypted_configuration(mclass) -> list:

static_ctor = next((m for m in mclass.Methods if m.IsStatic and m.Name == ".cctor"), None)

if not static_ctor or not static_ctor.HasBody:

print(f"Static constructor (.cctor) not found in class '{class_name}'.")

return []

constants = []

prev_instr = None # Track previous instruction

for instr in static_ctor.Body.Instructions:

if instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Stsfld and instr.Operand is not None:

field = instr.Operand

if prev_instr is not None:

# Extract the constant value from the previous instruction

if prev_instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldc_I4: # Integer constant

# constants.append(prev_instr.GetLdcI4Value())

# don't we only want string (encrypted configuration)

pass

elif prev_instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldc_R4: # Float constant

# constants.append(prev_instr.Operand)

# don't we only want string (encrypted configuration)

pass

elif prev_instr.OpCode == OpCodes.Ldstr: # String constant

constants.append(prev_instr.Operand)

prev_instr = instr # Update previous instruction

return constantsCode 11. Python function used to list encrypted string in the Settings class

Final Words

The final steps involve enumerating the decryption routine’s arguments and decoding the encrypted values using an appropriate Python cryptography library. A clearly defined strategy in the design phase, together with an optimized development environment, can significantly accelerate the extractor’s implementation. While this approach does not cover packed samples or certain QuasarRAT variants (for example, builds that substitute AES with another cipher), it delivers sufficiently accurate results for most real-world scenarios.

The full QuasarRAT extractor code is hosted in the Sekoia.io Community Git repository.

The techniques presented throughout this article demonstrate a systematic approach to extracting QuasarRAT’s encrypted configuration from both clean and obfuscated .NET samples. By combining a reproducible lab environment (Docker-packaged Jupyter Notebook, pythonnet and dnlib) with a thorough understanding of the .NET Intermediate Language, it becomes possible to:

- Locate and inspect critical classes (.cctor, Aes256, Settings).

- Recover cryptographic parameters (AES key, salt, IV, HMAC layout).

- Identify and invoke the decryption routine via IL instruction analysis.

- Assemble a fully automated Python extractor capable of harvesting C2 settings.

Although tailored to QuasarRAT, this workflow scales naturally to other .NET-based malware that rely on similar initialisation patterns and public-domain cryptography APIs. Its modular design, emphasizing namespace/class traversal, cross-reference resolution and opcode comparison, facilitates rapid adaptation to variants employing different obfuscators or minor algorithmic tweaks.

Remaining gaps include handling packed executables, non-AES algorithms, and custom runtime loaders. Future enhancements may introduce dynamic tracing or integration with deobfuscation pipelines to broaden coverage.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh