嗯,用户让我帮忙总结一篇文章的内容,控制在一百个字以内,而且不需要特定的开头。首先,我得仔细阅读文章,抓住主要信息。 文章是关于Sekoia威胁检测与研究团队如何自动化提取恶意软件配置数据的系列文章的第一篇。他们使用Assemblyline平台和ConfigExtractor服务,通过案例分析Kaiji物联网僵尸网络来展示流程。 我需要提炼出关键点:自动化提取配置数据、Assemblyline平台、ConfigExtractor服务、Kaiji案例、以及后续会分析.NET恶意软件。这些信息要在100字内简洁表达。 然后,组织语言,确保流畅且信息完整。比如:“本文介绍了Sekoia团队如何利用Assemblyline平台和ConfigExtractor服务自动化提取恶意软件配置数据,并以Kaiji物联网僵尸网络为例展示了具体流程。后续将分析.NET恶意软件的配置提取。” 这样既涵盖了主要内容,又符合字数限制。 </think> 本文介绍了Sekoia团队如何利用Assemblyline平台和ConfigExtractor服务自动化提取恶意软件配置数据,并以Kaiji物联网僵尸网络为例展示了具体流程。后续将分析.NET恶意软件的配置提取。 2025-12-1 08:31:47 Author: blog.sekoia.io(查看原文) 阅读量:1 收藏

This article is the opening chapter of a four-part Advent of Configuration Extraction series. The series outlines the methodology we employ at Sekoia’s Threat Detection & Research (TDR) team to automate the extraction of malware configuration data, from initial analysis to the production of usable intelligence. Each post of the series focuses on a different scenario, such as analysing .NET malware or using Capstone for disassembly, to show how the approach applies across various families and techniques.

This first article introduces Assemblyline, the analysis pipeline used by TDR and more specifically the configextractor service. To illustrate the workflow, we will use a simple case: the extraction of configuration data from Kaiji, an IoT botnet malware. This article provides a straightforward demonstration of how the pipeline operates and how the configuration extraction service interacts with the rest of the system.

How Assemblyline Organises Malware Analysis

Assemblyline is an open-source malware analysis platform developed by the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCCS). It structures analysis into a set of services, each responsible for a specific task in the processing chain. Among these services is the configuration extraction service, which identifies and processes configuration elements embedded within malware samples.

Overview and Workflow

Assemblyline operates as a staged pipeline. Each submitted file is processed by one or more services, selected according to predefined rules and service metadata. Services are grouped by stage, which determines the order in which they run. This allows earlier services to prepare or transform the input before later ones act on it. For example, a decompression or unpacking service can run in an early stage to expand an archive or extract inner components. The resulting files are then passed to downstream services, such as the configuration extractor, which can analyse them in their final, usable form. This staged approach ensures that each service receives the most relevant data and that the overall workflow remains predictable and modular.

Assemblyline provides several APIs that allow external systems to submit files for analysis and control how they are processed. Submissions can use predefined analysis templates that specify which services should run and in what configuration. At TDR, files are collected through various channels, including sharing malware samples platform, honeypots and open directory monitoring, and are automatically submitted to Assemblyline through these APIs. The samples are analysed by various Assemblyline services, including the configuration extractor, which produces indicators of compromise that are ingested directly into our threat intelligence database, ensuring that newly identified activity is quickly reflected in detection and monitoring workflows.

The ConfigExtractor service in Assemblyline is dedicated to extracting malware configuration data such as C2 domains, IPs, URLs or cryptographic material from analysed samples. It leverages the open‑source ConfigExtractor Python library also maintained by CCCS. While the service supports several extraction frameworks such as MWCP, MACO, and CAPE, our extractors are built using MACO. To keep up with new malware families, the service includes an updater component that pulls extractors from a private Git repository, dynamically loads them, and installs their dependencies as needed. By default, the service also pulls some public Git repositories.

MACO (Malware Analysis Configuration Objects) is a framework designed to standardise the extraction of malware configuration data across different families and formats. It provides a structured approach to define parsers for specific malware, specifying which elements to extract and how to normalise them. Within Assemblyline, the ConfigExtractor service integrates MACO parsers to process samples. When a parser matches a given malware type via YARA rules, MACO extracts the relevant configuration fields and returns them in a consistent, structured format. This allows downstream systems to automatically consume the data, such as feeding indicators of compromise into threat intelligence platforms, without requiring custom handling for each malware family.

All scripts used for configuration extraction by the service are called modules and follow a structured workflow.

- Library Imports: Load necessary libraries, including MACO, for parsing and structuring configuration data.

- Extractor Class: Define a class that calls the extraction logic and includes a YARA rule to identify relevant samples. When a sample matches the YARA rule, the extractor triggers the dedicated parsing logic.

- Extraction Logic: A set of dedicated functions or classes parse the sample and retrieve configuration fields. Placing this logic outside the main extractor class improves portability and allows reuse across different extractors or projects.

- Mapping to MACO Model: Extracted data is converted into a structured MACO model and returned to Assemblyline.

Kaiji is a botnet malware written in the Go programming language, primarily targeting Linux systems and IoT devices. Originally, it spread via SSH brute‑force attacks, trying to guess credentials on exposed root accounts. Via our honeypots, we also observed Kaiji spreading through vulnerability exploitation, notably targeting CVE‑2024‑7954 and CVE‑2023‑1389.

This evolution is particularly notable in the Chaos variant, a next‑generation successor analysed by Lumen, which not only retains Kaiji’s DDoS capabilities and reverse‑shell modules but also incorporates built-in vulnerability exploitation to target known CVEs, along with additional functionalities such as cryptocurrency mining.

Kaiji’s C2 Configuration Access Logic

To develop a configuration extractor, a preliminary manual analysis of multiple samples is required in order to identify the logic implemented by the malware to access and parse its configuration. For the present study, a static analysis was performed on sample 695909032488e34315857ef6da0c23eb1f6bba491c3c467a75e78228e0f289e4. Using IDA, it becomes immediately apparent that the binary is not obfuscated: the symbols remain intact and provide insight into the program’s structure. Among these, the function main_connect stands out as the component responsible for establishing the connection with the command‑and‑control (C2) infrastructure.

The first instructions within this function reveal the mechanism used to obtain the C2 address. The malware loads a Base64‑encoded string and decodes it using the Go runtime’s (*Encoding).DecodeString method. The returned byte slice is subsequently converted into a Go string through runtime_slicebytetostring. The resulting string is then split using the delimiter “|(odk)/*-“, with the portion appearing before the delimiter corresponding to the C2:Port tuple used for outbound communication.

A broader examination of the sample’s embedded strings provides additional context: the Base64‑encoded configuration string is consistently preceded by the marker “use ParseCertificate“, a pattern that has been observed across several related samples.

Based on this analysis, it becomes possible to implement a Python‑based configuration extractor. For this purpose, the FLOSS library is used and specifically its strings module, which provides the strings.extract_ascii_strings method for extracting all ASCII strings from a binary and returning them as a list. The extractor operates as follows:

- It uses this method to build a complete list of strings extracted from the binary.

- It iterates over this list and, using a regular expression, searches for and extracts the string prefixed with “use ParseCertificate“.

- It decodes the retrieved Base64 value, splits it using the delimiter “|(odk)/*-“, and retains only the first element, which corresponds to the C2:Port tuple.

The tuple is then further processed to isolate the C2 address and the port. A validation step determines whether the C2 value is an IP address or a domain name, allowing the extractor to select the appropriate macro context (server_ip or server_domain).

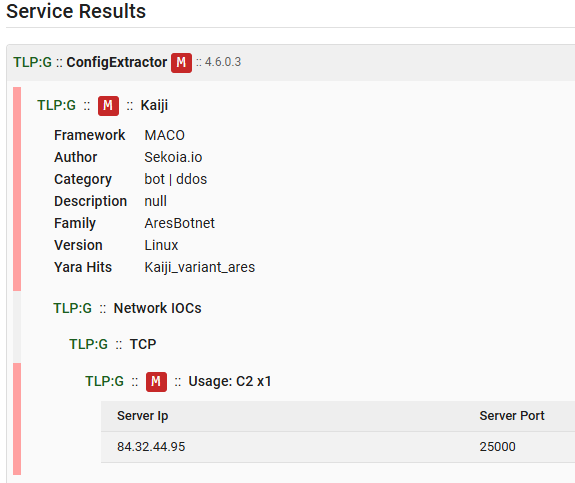

The extractor contains two YARA rules designed to identify Ares as well as Chaos variant. Below the configuration extraction service output, as shown in Assemblyline, for the analysed sample.

Final words

This article introduced the analysis pipeline used by TDR, with a particular focus on the methodology applied to extract malware configurations through Assemblyline. The process was illustrated using a first, relatively simple case: extracting the C2 information from the Kaiji variant malware, which relies primarily on parsing strings embedded in the binary.

Despite its simplicity, this example provides a clear understanding of how the ConfigExtractor service operates, its YARA‑based signature logic, its extraction workflow, and the formatting of results into the MACO schema.

In Part 2, we will continue this exploration by examining configuration extraction for .NET‑based malware, using the case of QuasarRAT as a more advanced and structured example.

Thank you for reading this blog post. Please don’t hesitate to provide your feedback on our publications by clicking here. You can also contact us at tdr[at]sekoia.io for further discussions or future IOCs.

Feel free to read other Sekoia.io TDR (Threat Detection & Research) analysis here:

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh