November 19, 2025 10 Minute Read 2025-11-19 16:56:27 Author: www.trustwave.com(查看原文) 阅读量:15 收藏

10 Minute Read

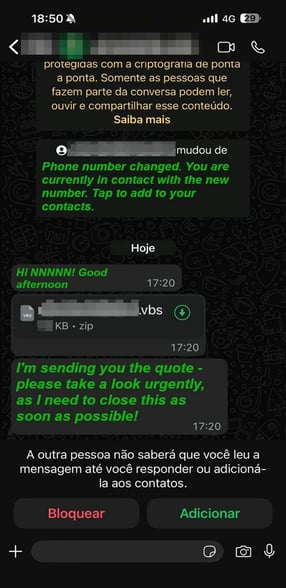

Trustwave SpiderLabs researchers have recently identified a banking Trojan we dubbed Eternidade Stealer, which is distributed through WhatsApp hijacking and social engineering lures. In this blog post, we will break down the techniques used in the campaign and highlight the new tools employed by the threat group. WhatsApp continues to be one of the most exploited communication channels in Brazil’s cybercrime ecosystem. Over the past two years, threat actors have refined their tactics, using the platform’s immense popularity to distribute banker trojans and information-stealing malware. Previous campaigns observed through 2024 and 2025, such as the Water Saci, show a clear evolution from simple phishing links to complex social engineering schemes involving fake government programs, delivery notifications, and even fraudulent investment groups shared through WhatsApp messages and groups. Building on this ongoing activity, the SpiderLabs Threat Research Team recently discovered a new stealer, Eternidade (Portuguese for “Eternity”), written in Delphi. It uses Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) to dynamically retrieve command-and-control (C2) addresses, allowing the threat actor to update its C2 server. It is distributed through a WhatsApp worm campaign, with the actor now deploying a Python script, a shift from previous PowerShell-based scripts to hijack WhatsApp and spread malicious attachments. Delphi remains a cornerstone of Brazil’s cybercrime ecosystem thanks to its mix of technical efficiency and regional familiarity. It enables quick development of native Windows executables that are easy to distribute, obfuscate, and integrate with the system API, making them ideal traits for stealthy, self-contained malware. Because Delphi was widely taught and used in legitimate Latin American software development during the 2000s and 2010s, many developers already mastered it before entering the underground scene. Over time, freely shared source code, cracked IDEs, and Portuguese-language tutorials made it even more accessible, while the success and resale of early Delphi-based banking trojans created a lasting feedback loop. Today, that foundation of shared knowledge and convenience keeps Delphi as one of the most preferred languages among Brazilian threat actors. The threat is far from theoretical. It’s happening in real time. While this research was being conducted, we received this snippet from one of the recipients of the message with a malicious VBScript. In the following sections, we analyze Eternidade’s features, infrastructure, and full infection chain, highlighting what sets this variant apart from earlier campaigns. The campaign begins via an obfuscated VBScript, with most of its comments written in Portuguese. When executed, the script drops a batch file that downloads and executes payloads: a WhatsApp-propagating worm and an MSI installer that deploys a Delphi-based banking trojan. The payloads are downloaded from the threat actor’s C2. The WhatsApp worm used in the campaign is written in Python, in contrast to the PowerShell variants reported recently. The dropper also installs the necessary Python dependencies for the payloads to run successfully. File Hash: SHA-256: 6168d63fad22a4e5e45547ca6116ef68bb5173e17e25fd1714f7cc1e4f7b41e1 In Figure 6, right on top of the script, we can directly see the intention of the C2, which is to establish C2 communication and generate unique session IDs for tracking infected machines. The campaign’s critical function is “obter_contatos()”, which allows the malware to steal victims’ entire WhatsApp contact lists. Figure 7 shows the JavaScript code it runs into the browser. WPP API Exploitation: The malware uses ‘WPP.contact.list()’, which is from the ‘wppconnect-w.js’ library and provides an API wrapper for WhatsApp Web. The malware downloads this library from GitHub to gain programmatic access to WhatsApp. Smart Filtering: Notice how the malware filters out groups (‘@g.us’), business contacts (‘@lid’), and broadcast lists. It optimizes the attack by focusing on individual contacts who are more likely to fall for phishing messages. The malware extracts the following information for each contact: Automatic Exfiltration: After collecting contacts, the Python code immediately calls ‘enviar_contatos_para_servidor()’. There is no delay, and no user interaction is needed. Contacts are stolen and sent to the C2 server as soon as they’re collected, without any opportunity to stop it. Each contact includes both the victim’s phone number and name, making it valuable for targeted attacks. The session ID and machine name allow attackers to correlate data from multiple infections. The data is then sent over HTTP POST in plaintext (though HTTPS is used, the data itself isn’t encrypted). As seen in Figure 9, the greeting automatically adjusts based on the time of day it is delivered (“bom dia,” “boa tarde,” and “boa noite” which translate to good morning, good afternoon, and good evening, respectively) and uses the contact’s actual name, mimicking legitimate business communications. The message template can be changed remotely by attackers via the C2 server. The malware downloads a malicious file from the C2 and converts Base64 to binary. It then sends a message to all contacts, along with a personalized greeting, a malicious file, and a follow-up message. It uses `waitForAck: false` to speed up delivery and avoid detection. Eternidade Stealer is delivered via a malicious MSI installer that drops multiple components including encrypted payloads and an AutoIt script loader. The “.log “ file appears to be an AutoIt-based malicious script that combines environment reconnaissance, anti-detection checks, and in-memory Portable Executable (PE)/shellcode loader behaviors commonly used to deliver banking trojans and credential stealers. The code contains large hex-encoded binary blobs used to initialize native payloads. The malware only targets Brazilian victims by checking the OS language. If the system is not detected as Brazilian Portuguese, it displays an error message and aborts execution. The script enumerates running processes and registry uninstall keys to detect installed security products. It also utilizes WMI to enumerate antivirus (AV)/firewall/anti-spyware products, collecting human-readable names (e.g., Kaspersky, Malwarebytes, Avast, Windows Defender) for decision-making or logging purposes. It contains functions that gather system telemetry, the external IP via an api.ipify.org call, and local IP collection, which are typical for staging and linking infected hosts back to C2 or operator dashboards. The function OBTERINFOADICIONAL() acts as a system-profiling routine that gathers basic host information and formats it into a single readable string. It first queries the Windows registry to retrieve the operating system’s product name, then collects the processor model from the hardware description keys. Using WMI, it accesses the Win32_ComputerSystem class to calculate the total amount of physical memory in gigabytes, providing an approximate measure of the machine’s RAM capacity. Finally, it captures the current logon domain from the system environment to indicate whether the host belongs to a corporate network or a local domain. Combined, these elements produce a concise hardware and system summary, preparing the malware operator with a quick profile of the infected machine configuration for further actions. The malware then sends the collected system information via POST method to its C2 `hxxps://itrexmssl[.]com/jasmin/altor/receptor[.]php`. Gathered information: The sample demonstrates a clear and highly localized targeting logic. It continuously scans active windows and running processes for strings associated with Brazilian banking portals, fintech services, and cryptocurrency platforms. When it detects a match, for example, a window title or process name linked to Bradesco, BTG Pactual, Binance, Coinbase, MetaMask, Trust Wallet, or another financial brand, the malware immediately decrypts and activates its next-stage payload. Such a behavior reflects a classic banker or overlay-stealer tactic, where malicious components lie dormant until the victim opens a targeted banking or wallet application, ensuring the attack triggers only in relevant contexts and remains invisible to casual users or sandbox environments. The malware searches for .tda or .dmp files in the installation folder, suggesting that this is not a one-off dropper but part of an operator-facing toolkit. If found, it first loads the .tda file, decrypts it using a custom stream cipher, and is decompressed using LZNT1 before running it in memory. Notably, the custom stream cipher is similar to those observed in both Casbaneiro and the Amavaldo injector. Below are snippets of the decryption algorithm reported by ESET and the one observed on this malware. The decrypted .tda file is a Delphi-compiled injector that performs process hollowing to run the final payload. The injector reads the .dmp file, decrypts it using the same routine mentioned above, and injects the Eternidade Stealer payload to svchost.exe. Eternidade Stealer is a Delphi-compiled credential stealer that harvests sensitive data and maintains an active connection to the infected host. When executed, it first checks for the Registry key “HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\MeuApp” and if the value “Inicio” (Portuguese for “Start”) exists. This serves as an infection marker to determine whether it has previously run on the machine. If it’s not present, it collects system information such as the computer name and processor information and sends it to serverseistemasatu[.]com/data.php?recebe via the HTTP POST method. It then proceeds to create the Registry key "MeuApp” and set the value of “Inicio” to True. It then enumerates all windows via the “EnumWindows” API,collects the following attributes, and parses it to the format shown below: Format: From the enumerated windows, the stealer specifically looks for applications associated with Brazilian banks, payment services, and cryptocurrency wallets/exchanges to target for credential harvesting. If a match is found, the malware establishes its connection with the C2 server. One notable feature of this malware is that it uses hardcoded credentials to log into its email account, from which it retrieves its C2 server. It is a very clever way to update its C2, maintain persistence, and evade detections or takedowns on a network level. If the malware cannot connect to the email account, it uses a hardcoded fallback C2 address. The following shows the procedure for retrieving the C2 server from the email: 2. Select Mailbox, in this sample “John” from Figure 26. 3. Retrieve the header from the most recent email. 4. Concatenate the email subject, sender, and recipient in the following format: Assunto: <Subject> 5. Search for the string “ip:” and extract the C2. 6. If not found, retrieve the email body and repeat the checking process. 7. If still not found, use the fallback C2 address (in this sample, “domimoveis1[.]com.br”). During investigation, we observed some samples were associated with email accounts where 2FA was not enabled by the threat actor, allowing access using only the hardcoded credentials. Using the credentials, we were able to log into the threat actor’s account and verify the behavior observed in the analysis. We also observed multiple encrypted strings used for C2 communications. This obfuscation delays static analysis and helps the sample evade static and signature‑based detection. The decryption routine uses a hardcoded key, “edit1” and salt, “MeuSaltPessoal#2024”. The detailed decryption procedure is as follows: Decrypting the strings, we found that the malware uses multiple commands to communicate with the C2 server. The malware waits for incoming messages from the C2 and parses them to determine which function to run. It implements multiple sockets, each dedicated to a specific function. Commands are sent by the C2 in the following format: Below are some of the commands observed in the sample: <|SocketMain|> When the malware receives the <|SocketMain|> command, it extracts the enclosed value, which is a unique identifier to the victim machine, and saves it. This is used to track individual hosts when sending information back to the C2. Collects the following information from the infected host: It then sends the gathered information back to the C2 in the following format: This is a core C2 command used to continuously monitor user activity and determine which malicious function the server should send next. When the command is received, the malware replies with <|PONG|>, sleeps for 100 ms, and reports the currently active window in the format shown below. This informs the threat actor which application the infected host is using, which is information that can be leveraged to deploy bank overlays or craft convincing phishing windows. Response Format: SendigTitle>{opened window} This command allows the threat actor to send a custom overlay for fake inputs to steal credentials. It sends it, along with specific parameters depending on the window the victim is accessing to create fake password input fields and submit button that is positioned over legitimate banking windows. With this, the victim unknowingly inputs credentials in the overlay field and exfiltrate it to the C2 server. Command received: The malware also implements hidden bank overlays targeting CAIXA Economica Federal and Banco do Brasil. This lets the victim unknowingly input banking information on the overlay instead of the legitimate one, and exfiltrate it to the C2 server. Below are the extracted overlays the malware used: Other commands observed are: activating keylogging features, sending captures or files, and other capabilities: <|AlterarResolucao|> <|AtivarImagem|> <|Chat|> <|CloseChat|> <|Close|> <|DELETEDKL|> <|DesativarImagem|> <|Destravar|> <|DownloadFile <|Files|> <|first|> <|Folder|> <|HOLENOFF|> <|HOLE|> <|MENSAGEM|> <|Metodo|> <|NOSenha|> <|OpenChat|> <|Reconected|> <|REQUESTKEYBOARD|> <|RESTART|> <|UploadFile|> From the analysis, we were able to pivot similar samples uploaded on VirusTotal. We identified similar malware dating back to January 2025, one of which was shared by researcher Dodo on Security (@dodo_sec) on X. The commands and functionalities found are similar, but earlier variants lacked the IMAP feature and used a hardcoded C2 address. These similarities suggest the same threat actor is behind the campaign and continues to actively develop the malware. Below are some of the similarities observed between the Eternidade Stealer and the older sample. From the initial URL, “serverseistemasatu[.]com,” we identified clusters of IP addresses sharing similar ASNs and response headers. We also analyzed the related domains hosted on these IP addresses. On one of these domains, we discovered additional threat actor panels: one for managing the Redirector System and another login panel, likely used to monitor infected hosts. The Redirector System panel contains logs showing the total visits and blocks for connections attempting to reach the C2 address. Access is restricted to machines located in Brazil and Argentina. Any blocked connections are redirected to https://google.com/error. Of the 453 visits recorded, 451 were blocked due to the geolocation restrictions enforced by the system. The statistics section from the panel offers a broader understanding of how many potential victims interacted with it. A total of 454 communication records were logged, reflecting contact attempts from a wide range of geographic locations. While it cannot be confirmed that every entry represents an active infection tied directly to this campaign, the volume and diversity of the data strongly suggests that the redirection module was accessed or pinged by potential victims around the world, not just within the primary target region. In total, communications originated from 38 countries, with the highest activity observed in the United States (196 connections), followed by The Netherlands (37), Germany (32), United Kingdom (23), and France (19). Only two communications were successfully redirected to the campaign’s targeted domain. Only three connections were made from Brazilian IP addresses, implying that although the malware family and delivery vectors are primarily Brazilian, the possible operational footprint and victim exposure are far more global. Operating system statistics indicated a predominantly desktop-based exposure pattern across the 454 recorded communications. The majority of connections, 182 (40%), originated from Unknown OS types, suggesting incomplete or obfuscated user-agent data, possibly from automated tools or anonymized proxies. Windows systems accounted for 115 connections (25%), followed by macOS with 94 (21%), while Linux represented 45 connections (10%) and Android only 18 (4%). These statistics confirm the infrastructure was primarily contacted by desktop users, reinforcing the assumption that the campaign targeted proper workstation environments rather than mobile endpoints, and indicating a mixed ecosystem of potential victims and a global spread. In the Configuration tab, the panel shows settings for redirection (for permitted and blocked connections), allowed countries, and connections per IP. It also includes checkboxes to enable anti-bot protection, block VPNs and proxies, block hosting servers, block suspicious IPs, block empty or non-browsing user-agents, and other related protections. There is also an input field for a list of IP addresses that are always allowed to connect, bypassing all other checks. Eternidade Stealer is an active, evolving threat that highlights two concerning trends: the growing use of WhatsApp as a distribution vector, and the malware’s continued development, including dynamic IMAP-based C2 retrieval, improved evasion techniques, and geofencing to target Brazilian victims. Cybersecurity defenders should remain vigilant for suspicious WhatsApp activity, unexpected MSI or script executions, and indicators linked to this ongoing campaign. VBS: Whats.py: Payload: Domains: IPs

Figure 1. The message received via WhatsApp during the preparation of the current report.Technical Analysis

Figure 2. Eternidade Stealer’s attack chain.

Figure 3. Obfuscated VBScript with comments written in Portuguese.

Figure 4. Function to drop next stage payload.WhatsApp Propagating Worm

Figure 5. 1,300+ line piece of Python script (whats.py) designed to automate WhatsApp messaging, steal contact lists, and distribute malicious files.

Figure 6. Initialization of C2 endpoints.Stealing WhatsApp Contacts: Core Functionality

Figure 7. The malware’s JavaScript code that steals victims’ WhatsApp contact lists.Breaking Down the Attack

Data Exfiltration: Sending Stolen Contacts to C2

Figure 8. The malware’s data exfiltration script in Python.Message Template Used

Figure 9. The message template used in the campaign.Malware Distribution: Attack Vector

Figure 10. Script for malware distribution.MSI Dropper

Figure 11. Malicious files dropped by the Installer.

Figure 12. Error message shown if the system is not detected as Brazilian Portuguese.

Figure 13. Script verifying the OS language used.

Figure 14. The malware detects security products installed in the victim’s machine.

Figure 15. The malware detects anti-spyware and anti-virus products installed in the victim’s machine.

Figure 16. The malware gathers system telemetry.%20function.jpg?width=1430&height=438&name=Figure%2017.%20The%20malware%E2%80%99s%20OBTERINFOADICIONAL()%20function.jpg)

Figure 17. The malware’s OBTERINFOADICIONAL() function.

Figure 18. The list of information gathered by the malware.

Figure 19. The malware scans for strings associated with Brazilian banking portals, fintech services, and cryptocurrency platforms.Payload Decryption

Figure 20. The malware scans for the presence of .tda and .dmp files in the installation folder.

Figure 21. The steam cipher used in the Casbaneiro banking trojan. Source: We Live Security by ESET.

Figure 22. Python implementation of the decryption used.

Figure 23. Actual code for payload decryption.Injector Payload

Figure 24. The injector performs process hollowing to run the Eternidade Stealer.Eternidade Stealer

Titulo: <Window Title> | Class: <Class Name: | Exe: <Executable Path>

Figure 25. The Eternidade Stealer collects the Window title, class name, and executable path information.

Santander

Banco do Brasil

Banrisul

Tribanco

Bradesco

Sicredi

Sicoob

BMG

BTG Pactual

BS2

Itaú

Caixa Econômica Federal (CEF)

Banco Mercantil

Banco do Nordeste (BNB)

Banco da Amazônia

MercadoPago

RecargaPay

Stripe

Binance

OKX

Crypto.com

Coinbase

Foxbit

Novadax

Bitget

Bybit

Coinext

Kucoin

Kraken

Bitstamp

Bitfinex

Poloniex

Huobi

Gate.io

Gemini

Electrum

Exodus

Atomic Wallet

MetaMask

Ledger Live

Trust Wallet

Blockchain.com

Coinomi

Phantom Wallet

Solflare

TokenPocket

Math Wallet

Figure 26. The malware uses hardcoded credentials to log into its email account.

1. Connect to the IMAP server via SSL (Port 993) using hardcoded credentials.

Figure 27. Hardcoded credentials are used to connect to the IMAP server.

De: <Sender Email Address>

Para: <Recipient Email Address>

Figure 28. The malware concatenates the most recent email’s email subject, sender, and recipient.

Figure 29. The threat actor’s email account accessed by SpiderLabs researchers via hardcoded credentials.Backdoor Commands and Capabilities

Figure 30. Encrypted strings used for C2 communications.

Figure 31. Python implementation of the decryption routine.

Figure 32. The <|SocketMain|> command.

<|OK|>

<|Info|>{collected info1}<|>{collected info2}....<|>{message}<<|

Figure 33. The <|OK|> command.

<|PING|>

Figure 34. The <|PING|> command.

<|PedidoSenhas|><|PedidoSenhas|><|>EditPassword.Top={}<|>EditPassword.Left={}<|>EditPassword.PromptText={}<|>EditPasswordStyle={}<|>ButtonOk.Top={}<|>ButtonOk.Left={}<|>TamanhoImagem.Width={}<|>TamanhoImagem.Height={}

<|CE_ASSI|> , <|CE_TRANS|> and <|CB_SEN|>

Figure 35. Banking overlay the malware uses to trick victims into inputting their banking information.

Figure 36. Dodo on Security’s X post about a banking trojan similar to the Eternidade Stealer.

Figure 37. Eternidade Stealer: sending info to C2 server.

Figure 38. Old sample shared with similar function as the Eternidade Stealer.

Figure 39. Eternidade Stealer with encrypted strings.

Figure 40. Old sample with encrypted strings.Malware Panel

![Figure 41. IP addresses related to “serverseistemasatu[.]com”](https://www.trustwave.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Blogs/SpiderLab_Blog_Images/Figure%2041.%20IP%20addresses%20related%20to%20%E2%80%9Cserverseistemasatu%5B.%5Dcom%E2%80%9D.jpg?width=536&height=487&name=Figure%2041.%20IP%20addresses%20related%20to%20%E2%80%9Cserverseistemasatu%5B.%5Dcom%E2%80%9D.jpg)

Figure 41. IP addresses related to “serverseistemasatu[.]com”

Figure 42. Domains hosted on one of the IP addresses.

Figure 43. A login panel likely used for monitoring infected hosts.

Figure 44. Redirector System’s login panel.

Figure 45. Redirector System’s connections logs.

Figure 46. Redirector System’s statistics panel.

Figure 47. Operating system distribution across observed panel data.

Figure 48. Redirector System’s configuration tab.

Figure 49. Redirector System’s input field for allowed list of IP addresses.![216.234.208[.]0](https://www.trustwave.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Blogs/SpiderLab_Blog_Images/216.234.208%5B.%5D0.jpg?width=788&height=401&name=216.234.208%5B.%5D0.jpg)

Conclusion

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh