2020-09-24 01:00:00 Author: www.forcepoint.com(查看原文) 阅读量:155 收藏

Ponemon Institute Privileged User Survey

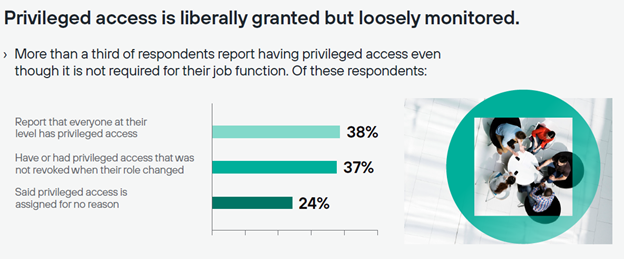

In surveying nearly 900 self-described privileged users—those who have higher-level access than your standard employee—in UK and US government, 36 percent said they did not need privileged access to do their jobs but had it anyway. The main reasons for such access were that everyone at their level had it or that organizations failed to revoke particular rights when an employee’s role changed. Some IT pros even indicated that the organization assigned privileged access for no apparent reason—a particularly worrying trend, considering almost half of respondents say privileged users may access sensitive or confidential data out of curiosity, while 44% cited the issue of privileged users being pressured to share access with others.

As government organizations on both sides of the pond look to improve their security postures, addressing privileged user access is an obvious first step. But the survey showed many IT teams are struggling to keep up with the sheer volume of access change requests—particularly when they are relying on old-school systems like spreadsheets. It should come as no surprise, then, that so many organizations also lack enterprise-wide visibility into who has privileged user access, much less monitoring capabilities into what those users are doing.

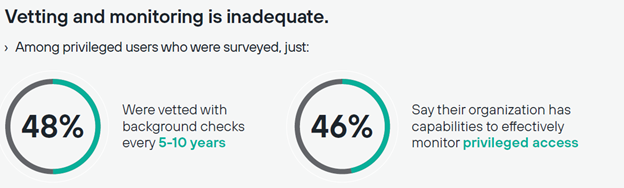

Only about half of government respondents reported that privileged users are vetted through thorough background checks, or that access is monitored through identity and access management (IAM) tools or provisioning systems. Worse, only 11% expressed confidence in their organization’s enterprise-wide visibility. When security tools are in place, they tend to be bogged down by false positives, swamped by the amount of data in play, or are unable to sort malicious behavior from the status quo.

The risk caused by privileged users—who include database administrators, network engineers, IT security practitioners and cloud custodians in this survey —isn’t new, nor is it going away. Unfortunately, the over-granting of privileged access and the lack of visibility into who has it seem to be here to stay as well. A whopping 85 percent of survey respondents said the risk will either remain the same or increase in coming years.

The sheer number of privileged users makes, to some extent, abuse inevitable. But abuse doesn’t have to snowball into a full-blown data breach. One of the keys to mitigating privileged user abuse is behavior and user activity monitoring, which can determine the context and intent of a particular user’s actions. User activity monitoring requires the ability to correlate activity from keystrokes, badge records, and more. It should also include capabilities like DVR-like playback to discern end-user intent. Robust automation is key to ensuring this level of monitoring doesn’t create friction for employees trying to do their jobs, too. Behavior analytics uses Indicators of Behavior (IOBs) to determine the riskiness of behavior using a mix of IT data, non-IT data and psychological factors to understand risks early. Making it possible to take proactive actions, based on the risk level, to mitigate that risk through the application of granular policies to move “left of loss”.

Without granular visibility—visibility not just into who has access, but what they’re doing with it—organizations can’t detect or react to compromised or malicious access fast enough to stay protected. The key principle here is a zero-trust motto: “never trust, always verify” particularly since the privileged user threat shows no sign of diminishing. Economic pressure leads to short-staffed companies, which leads to stressed employees who are more likely to cut corners in ways that threaten security. Especially now, real-time visibility into user access and actions should be non-negotiable.

In an IT setting, privilege can mean many things: access to a particular application or data set; permission to shut down or configure systems; authority to bypass certain security measures. In some cases, this privilege is required of an urgent task. In others, it represents not just unnecessary access, but unnecessary risk. Organizations must do a better job of tracking not just access, but behavior once that access is granted, in order to prevent and respond to data breaches.

Click the green Read the Report button to access the full report.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh