2025年第三季度网络激进主义攻击几乎翻倍,尤其是针对工业控制系统的攻击增加。俄罗斯相关组织如Z-Pentest等成为主要威胁,目标为能源、制造和农业部门。部分团体转向勒索软件活动。 2025-10-31 12:46:23 Author: cyble.com(查看原文) 阅读量:11 收藏

Hacktivist attacks on industrial control systems (ICS) nearly doubled over the course of the third quarter.

Hacktivist attacks on critical infrastructure grew throughout the third quarter of 2025, and by September, accounted for 25% of all hacktivist attacks.

If that trend continues, it would represent a near-doubling of attacks on industrial control systems (ICS) from the second quarter of 2025.

Cyble’s assessment of the hacktivism threat landscape in the third quarter of 2025 found that while DDoS attacks and website defacements continue to comprise a majority of hacktivist activity, their share continues to decline, as ideologically-motivated threat groups expand their focus to include ICS attacks, data breaches, unauthorized access, and even ransomware.

Z-Pentest emerged in the fall of 2024 as the hacktivist group most targeting ICS systems, but in the third quarter the threat group was also joined by Dark Engine (aka Infrastructure Destruction Squad), Golden Falcon Team, INTEID, S4uD1Pwnz, and Sector 16.

Russia-aligned hacktivist groups INTEID, Dark Engine, Sector 16, and Z-Pentest were responsible for the majority of recent ICS attacks, primarily targeting Energy & Utilities, Manufacturing, and Agriculture sectors across Europe. Their campaigns focused on disrupting industrial and critical infrastructure in Ukraine, EU and NATO member states.

Some of Z-Pentest’s targets in the third quarter included a water utility HMI system in the U.S. and an agricultural biotechnology SCADA system in Taiwan. The group often posts videos of its members tampering with critical infrastructure control panels, as they did in the recent U.S. and Taiwan incidents.

Critical infrastructure attacks by hacktivist groups have continued into the fourth quarter, and the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security just this week warned of ICS attacks in that country.

Most Active Hacktivist Groups and Targets

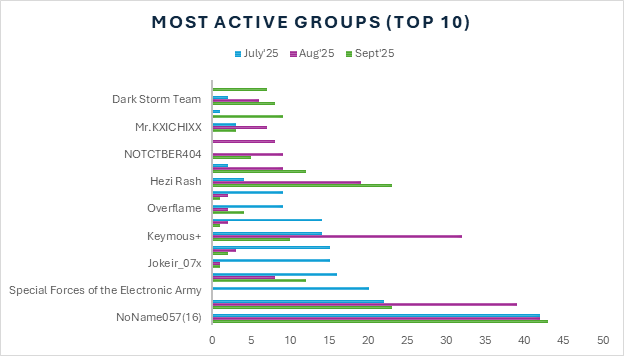

NoName057(16) retained the largest share of observable operations despite attempts by law enforcement to disrupt the threat group. Z-Pentest and Hezi Rash increased their proportional footprint, together representing a meaningful slice of activity compared with the start of the quarter. Several once-prominent actors contracted sharply: Special Forces of the Electronic Army, Jokeir_07x, and BL4CK CYB3R all lost ground, their relative contributions dwindling to a marginal portion. A handful of emerging groups — including Red Wolf Cyber Team and INTEID — strengthened their visibility and now constitute a notable minority.

The chart below shows the most active hacktivist groups in the third quarter.

Among the noteworthy incidents in the quarter, the Belarusian group Cyber Partisans BY, together with Silent Crow, claimed to have compromised the IT infrastructure of Russian state airline Aeroflot, exploiting alleged Tier-0 access for nearly a year. The attackers reportedly gained control over significant IT assets, disrupting key systems and exfiltrating more than 22TB of data. Russia’s General Prosecutor confirmed a cyberattack that caused major flight delays and cancellations at Sheremetyevo Airport. The groups also claimed the destruction of around 7,000 servers.

The Ukrainian Cyber Alliance and BO Team announced a breach of a Russian manufacturer involved in military drone production. Leaked materials purportedly included engineering blueprints, VMware snapshots, storage mappings, and CCTV footage from UAV assembly facilities. The attackers claimed they wiped servers, backups, and cloud environments after data exfiltration.

Among the hacktivist groups moving into ransomware, Team BD Cyber Ninja’s “Black Hat” division claimed to have released a custom ransomware tool that they advertise as “100% FUD” (fully undetectable), able to encrypt Windows systems and lock the disk at the Master Boot Record (MBR), rendering affected hosts non-bootable. The group’s claims remain unverified.

The hacktivist collective Liwa’ Muhammad announced the release of its Ransomware-as-a-Service (Raas) with a double-extortion model, named ‘BQTLock’ (BaqiyatLock) in July. The group claims multiple Raas variants for encrypting Linux, Windows, and macOS systems.

Among the sectors targeted during the third quarter, government and law-enforcement targets continued to dominate, but their share declined markedly, dropping from nearly one-third of all incidents in July to about one-quarter by September. Energy and Utilities grew proportionally, expanding their share by almost half, while Telecommunications and Media each recorded moderate proportional gains.

Below is a chart showing sectors targeted by hacktivist groups in the third quarter.

Hacktivism and Geopolitical Conflict

Geopolitical conflict remains a primary motive in hacktivist campaigns.

Hacktivist campaigns in Southeast Asia illustrated how border tensions rapidly translated into coordinated digital offensives. The Thailand–Cambodia border conflict triggered intense cross-border cyber aggression, with nationalist groups leveraging DDoS attacks, website defacements, and data leaks to reinforce territorial narratives. However, as regional hostilities eased, the focus shifted away from Southeast Asia toward new flashpoints.

In South Asia, hacktivism remained highly reactive to political symbolism and historical grievances. The India–Pakistan and India-Bangladesh rivalries once again shaped cyberspace, with both sides conducting retaliatory and ideologically framed attacks. These operations were amplified by disinformation efforts seeking to portray cyber incidents as extensions of insurgent activity.

The Middle East continued to experience a digital spillover from ongoing physical conflicts. The Israel–Hamas war has fueled a surge in politically motivated cyber activity. In response to Israel’s blockade and military operations, pro-Palestinian and Islamist-aligned hacktivists intensified campaigns against Egypt, Israel, and their regional allies. The Houthi–Saudi Arabian conflict added to regional instability, with hacktivist groups aligned with both Saudi and Houthi interests conducting cyber operations in support of their respective sides.

In Europe, the dismantling of NoName057(16) infrastructure under Operation Eastwood triggered retaliatory activity by pro-Russian networks, reaffirming the resilience and adaptability of state-aligned hacktivist ecosystems. Simultaneously, the Russia–Ukraine war and broader confrontation with NATO drove sustained cyber aggression across Eastern and Northern Europe, particularly in the Baltic States and Finland.

A notable trend emerged in the Philippines, where domestic political unrest and corruption scandals invited a surge in cyberattacks against state institutions. This rise underscored the increasing use of hacktivism as a tool of internal dissent.

Most Targeted Countries by Hacktivists

Ukraine was the leading target of hacktivist campaigns in the third quarter, primarily due to the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war and associated proxy cyber activity from pro-Russian groups and their international allies.

In contrast, Thailand and India—previously among the most targeted states—experienced a sharp contraction in hacktivist operations. The downturn aligned with the easing of border hostilities between Thailand and Cambodia and the fading of nationalist cyber campaigns surrounding India’s Independence Day.

Meanwhile, the Philippines emerged unexpectedly as a high-profile target following domestic unrest and allegations of government corruption, marking a regional pivot within Southeast Asia.

Saudi Arabia and Finland saw renewed exposure, each linked to broader geopolitical developments—Saudi Arabia’s involvement in regional conflicts, especially with the Houthis militia in Yemen, and Finland’s integration into NATO’s security framework. Egypt and the UAE continued to attract low but persistent activity tied to Middle Eastern crises, particularly the Gaza–Egypt border tensions. The United States maintained a steady, symbolic presence as a target, while Morocco and Italy registered modest increases consistent with wider European and North African instability.

Conclusion

The growing sophistication of the leading hacktivist groups is by now an established trend and will likely continue to spread to other groups over time.

That means that exposed environments in critical sectors can expect further compromise by hacktivist groups, advanced persistent threats (APTs), and others known to target critical infrastructure.

Critical assets should be isolated from the Internet wherever possible, and operational technology (OT) and IT networks should be segmented and protected with Zero Trust access controls. Vulnerability management, along with network and endpoint monitoring and hardening, is another critical cybersecurity best practice.

Cyble’s comprehensive attack surface management solutions can help by scanning network and cloud assets for exposures and prioritizing fixes, in addition to monitoring for leaked credentials and other early warning signs of major cyberattacks. Get a free external threat profile for your organization today.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh