现代科技工具使用时会不自觉泄露大量信息,区分公开与私密传播至关重要。人们常低估公开信息的广泛性和持久性,并可能被用于商业或威胁用途。防御措施包括提高意识和减少个人信息暴露。 2025-9-25 08:16:16 Author: www.adainese.it(查看原文) 阅读量:14 收藏

Every time we use a technological tool (smartphone, computer, and beyond), we disseminate—whether intentionally or not—an enormous amount of information. Very few people actually stop to consider the potential consequences of this behavior.

Many continue to claim “I have nothing to hide”, an argument that always reminds me of the image of an ostrich burying its head in the sand.

Information Dissemination vs. Information Communication

As a preliminary note, and for the purposes of this article, we will use “information communication” to describe actions where the confidentiality of the channel is implied (e.g., a direct message). Conversely, “information dissemination” refers to actions where the public nature of the channel is implicit (e.g., a public feed or bulletin board). In both cases, the action is voluntary.

I often find myself reflecting with others on how the use of technology frequently leads to misperceptions. While posting a status update on a social network clearly implies that it will be visible to others, few are fully aware that this content can be accessed by anyone in the world, from now on, potentially forever.

This lack of awareness can be attributed to a persistent misperception: when interacting with a social network, I am likely sitting safely at home or in an office, perhaps even alone. In reality, however, I am standing before a vast, crowded audience of potentially billions of people—and not just people. I am also subject to automated systems (bots, crawlers, scrapers) eagerly collecting my data. These entities simply have no equivalent in the physical world, making it difficult for us to be cautious about something we cannot fully comprehend.

Another misperception involves communications assumed to be private: it is evident how easy it is to make “confidential” information public. Yet when we digitally communicate with someone, we rarely pause to consider this risk.

Data Misappropriation

It is crucial to emphasize that everything made public online becomes a potential target for automated tools designed to collect and archive data. These datasets are then monetized—sold or leased to customers.

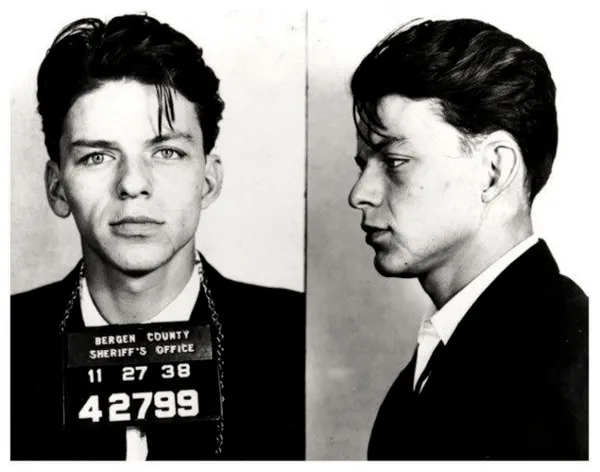

In other words, anything we make accessible can be commodified. The most well-known example is personalized advertising, which requires millions of categorized user profiles. But emerging products raise additional concerns, such as Clearview AI, which has built a massive facial-recognition database from publicly available images (including social media content), offered for lease to federal agencies.

With high probability, most of us are already catalogued.

In the near future, such databases may become commercially accessible. Anyone with a photo of a person could retrieve correlated information: other images, blog posts, social profiles… and this data is likely stored indefinitely.

A stalker’s paradise.

Threat Modeling

This leads to the central issue: how can the information I communicate or disseminate become a threat to me, my family, or my organization?

It is evident that someone with access to my history, comments, or opinions could selectively weaponize messages to discredit me in any context.

Likewise, a data breach—such as the one involving Ho Mobile—enables identity theft by anyone with minimal technical knowledge.

The more data a potential attacker gathers, the more sophisticated the fraud attempts will become. Thinking “why would anyone target me?” is once again burying one’s head in the sand. Cyber fraud is, in most cases, a business model designed to maximize profit with minimal effort. The profit derives, once again, from what I can provide, often under coercion. That “provision” may take the form of money, but also of actions or omissions: exfiltrating corporate projects, installing a device within a company network, or overlooking an investigation.

Defensive Measures

The solution lies in strengthening our awareness while reducing the trail of personal information we leave behind.

In Zanshin Tech training sessions, a practical exercise highlights the importance of personal data: each participant receives physical cards, each representing a specific type of information (nickname, profile photo, full name, address, religion, sexual orientation, health conditions, intimate images, etc.). The exercise simulates a digital conversation through the exchange of cards. The key insight is clear: once a card is handed over, the original owner loses control, and the recipient can do with it as they wish.

Personally, I recommend a simple rule of thumb before sharing any piece of information: if it could be publicly posted in a town square, then it may be communicated or published. Otherwise, it should not. I apply this principle universally—to private messages, emails, and public posts alike.

Conclusion

This article aims to establish a baseline of awareness around the actions modern technologies have made so effortless: writing, communicating, sharing, expressing opinions, judgments, and emotions.

Beyond reflecting on what to share, with whom, where, and how, I encourage everyone to first ask “should I share this at all?”. The resulting self-awareness will lead us to better understand the underlying impulse that drives us to share, to participate in a digital community that is vastly different from its physical counterpart. That very impulse, which we reveal every time we post, is—especially to those reading between the lines, extremely valuable information.

References

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh