本文详细介绍了Windows注册表的内部结构,包括_HHIVE和_CMHIVE结构体的作用与功能。_HHIVE负责管理内存状态、文件操作和同步锁等低级功能;_CMHIVE则处理安全描述符缓存、事务管理和键控制块(KCB)等高级功能。KCB是键管理的核心对象,通过树形结构实现高效的键查找与操作。 2025-4-16 21:19:0 Author: googleprojectzero.blogspot.com(查看原文) 阅读量:12 收藏

Posted by Mateusz Jurczyk, Google Project Zero

Welcome back to the Windows Registry Adventure! In the previous installment of the series, we took a deep look into the internals of the regf hive format. Understanding this foundational aspect of the registry is crucial, as it illuminates the design principles behind the mechanism, as well as its inherent strengths and weaknesses. The data stored within the regf file represents the definitive state of the hive. Knowing how to parse this data is sufficient for handling static files encoded in this format, such as when writing a custom regf parser to inspect hives extracted from a hard drive. However, for those interested in how regf files are managed by Windows at runtime, rather than just their behavior in isolation, there's a whole other dimension to explore: the multitude of kernel-mode objects allocated and maintained throughout the lifecycle of an active hive. These auxiliary objects are essential for several reasons:

- To track all currently loaded hives, their properties (e.g., load flags), their memory mappings, and the relationships between them (especially for delta hives overlaid on top of each other).

- To synchronize access to keys and hives within the multithreaded Windows environment.

- To cache hive information for faster access compared to direct memory mapping lookups.

- To integrate the registry with the NT Object Manager and support standard operations (opening/closing handles, setting/querying security descriptors, enforcing access checks, etc.).

- To manage the state of pending transactions before they are fully committed to the underlying hive.

To address these diverse requirements, the Windows kernel employs numerous interconnected structures. In this post, we will examine some of the most critical ones, how they function, and how they can be effectively enumerated and inspected using WinDbg. It's important to note that Microsoft provides official definitions only for some registry-related structures through PDB symbols for ntoskrnl.exe. In many cases, I had to reverse-engineer the relevant code to recover structure layouts, as well as infer the types and names of particular fields and enums. Throughout this write-up, I will clearly indicate whether each structure definition is official or reverse-engineered. If you spot any inaccuracies, please let me know. The definitions presented here are primarily derived from Windows Server 2019 with the March 2022 patches (kernel build 10.0.17763.2686), which was the kernel version used for the majority of my registry code analysis. However, over 99% of registry structure definitions appear to be identical between this version and the latest Windows 11, making the information directly applicable to the latest systems as well.

Hive structures

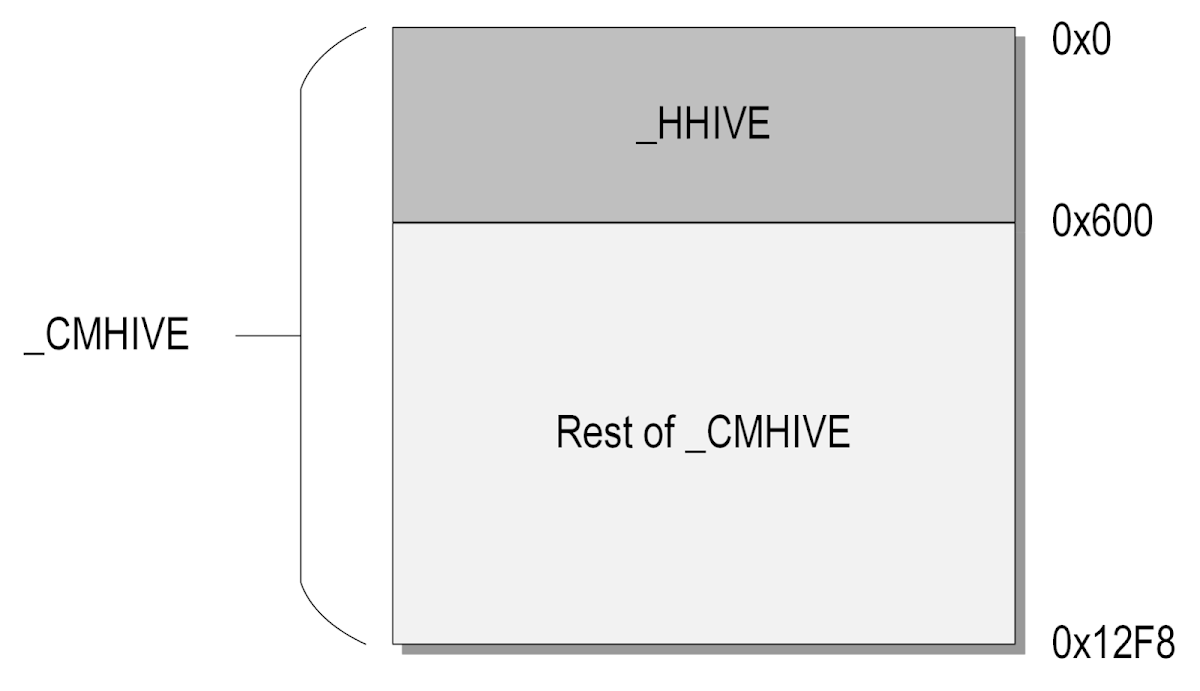

Given that hives are the most intricate type of registry object, it's not surprising that their kernel-mode descriptors are equally complex and lengthy. The primary hive descriptor structure in Windows, known as _CMHIVE, spans a substantial 0x12F8 bytes – exceeding 4 KiB, the standard memory page size on x86-family architectures. Contained within _CMHIVE, at offset 0, is another structure of type _HHIVE, which occupies 0x600 bytes, as depicted in the diagram below:

This relationship mirrors that of other common Windows object pairs, such as _EPROCESS / _KPROCESS and _ETHREAD / _KTHREAD. Because _HHIVE is always allocated as a component of the larger _CMHIVE structure, their pointer types are effectively interchangeable. If you encounter a decompiled access using a _HHIVE* pointer that extends beyond the size of the structure, it almost certainly indicates a reference to a field within the encompassing _CMHIVE object.

But why are two distinct structures dedicated to representing a single registry hive? While technically not required, this separation likely serves to delineate fields associated with different abstraction layers of the hive. Specifically:

- _HHIVE manages the low-level aspects of the hive, including the hive header, bins, and cells, as well as in-memory mappings and synchronization state with its on-disk counterpart (e.g., dirty sectors).

- _CMHIVE handles more abstract information about the hive, such as the cache of security descriptors, pointers to high-level kernel objects like the root Key Control Block (KCB), and the associated transaction resource manager (_CM_RM structure).

The next subsections will provide a deeper look into the responsibilities and inner workings of these two structures.

_HHIVE structure overview

The primary role of the _HHIVE structure is to manage the memory-related state of a hive. This allows higher-level registry code to perform operations such as allocating, freeing, and marking cells as "dirty" without needing to handle the low-level implementation details. The _HHIVE structure comprises 49 top-level members, most of which will be described in larger groups below:

0: kd> dt _HHIVE

nt!_HHIVE

+0x000 Signature : Uint4B

+0x008 GetCellRoutine : Ptr64 _CELL_DATA*

+0x010 ReleaseCellRoutine : Ptr64 void

+0x018 Allocate : Ptr64 void*

+0x020 Free : Ptr64 void

+0x028 FileWrite : Ptr64 long

+0x030 FileRead : Ptr64 long

+0x038 HiveLoadFailure : Ptr64 Void

+0x040 BaseBlock : Ptr64 _HBASE_BLOCK

+0x048 FlusherLock : _CMSI_RW_LOCK

+0x050 WriterLock : _CMSI_RW_LOCK

+0x058 DirtyVector : _RTL_BITMAP

+0x068 DirtyCount : Uint4B

+0x06c DirtyAlloc : Uint4B

+0x070 UnreconciledVector : _RTL_BITMAP

+0x080 UnreconciledCount : Uint4B

+0x084 BaseBlockAlloc : Uint4B

+0x088 Cluster : Uint4B

+0x08c Flat : Pos 0, 1 Bit

+0x08c ReadOnly : Pos 1, 1 Bit

+0x08c Reserved : Pos 2, 6 Bits

+0x08d DirtyFlag : UChar

+0x090 HvBinHeadersUse : Uint4B

+0x094 HvFreeCellsUse : Uint4B

+0x098 HvUsedCellsUse : Uint4B

+0x09c CmUsedCellsUse : Uint4B

+0x0a0 HiveFlags : Uint4B

+0x0a4 CurrentLog : Uint4B

+0x0a8 CurrentLogSequence : Uint4B

+0x0ac CurrentLogMinimumSequence : Uint4B

+0x0b0 CurrentLogOffset : Uint4B

+0x0b4 MinimumLogSequence : Uint4B

+0x0b8 LogFileSizeCap : Uint4B

+0x0bc LogDataPresent : [2] UChar

+0x0be PrimaryFileValid : UChar

+0x0bf BaseBlockDirty : UChar

+0x0c0 LastLogSwapTime : _LARGE_INTEGER

+0x0c8 FirstLogFile : Pos 0, 3 Bits

+0x0c8 SecondLogFile : Pos 3, 3 Bits

+0x0c8 HeaderRecovered : Pos 6, 1 Bit

+0x0c8 LegacyRecoveryIndicated : Pos 7, 1 Bit

+0x0c8 RecoveryInformationReserved : Pos 8, 8 Bits

+0x0c8 RecoveryInformation : Uint2B

+0x0ca LogEntriesRecovered : [2] UChar

+0x0cc RefreshCount : Uint4B

+0x0d0 StorageTypeCount : Uint4B

+0x0d4 Version : Uint4B

+0x0d8 ViewMap : _HVP_VIEW_MAP

+0x110 Storage : [2] _DUAL

Signature

Equal to 0xBEE0BEE0, it is a unique signature of the _HHIVE / _CMHIVE structures. It may be useful in digital forensics for identifying these structures in raw memory dumps, and is yet another reference to bees in the Windows registry implementation.

Function pointers

Next up, there are six function pointers, initialized in HvHiveStartFileBacked and HvHiveStartMemoryBacked, and pointing at internal kernel handlers for the following operations:

|

Pointer name |

Pointer value |

Operation |

|

GetCellRoutine |

HvpGetCellPaged or HvpGetCellFlat |

Translate cell index to virtual address |

|

ReleaseCellRoutine |

HvpReleaseCellPaged or HvpReleaseCellFlat |

Release previously translated cell index |

|

Allocate |

CmpAllocate |

Allocate kernel memory within global registry quota |

|

Free |

CmpFree |

Free kernel memory within global registry quota |

|

FileWrite |

CmpFileWrite |

Write data to hive file |

|

FileRead |

CmpFileRead |

Read data from hive file |

As we can see, these functions provide the basic functionality of operating on kernel memory, cell indexes, and the hive file. In my opinion, the most important of them is GetCellRoutine, whose typical destination, HvpGetCellPaged, performs the cell map walk in order to translate a cell index into the corresponding address within the hive mapping.

It is natural to think that these function pointers could prove useful for exploitation if an attacker managed to corrupt them through a buffer overflow or a use-after-free condition. That was indeed the case in Windows 10 and earlier, but in Windows 11, these calls are now de-virtualized, and most call sites reference one of HvpGetCellPaged / HvpGetCellFlat and HvpReleaseCellPaged / HvpReleaseCellFlat directly, without referring to the pointers. This is great for security, as it completely eliminates the usefulness of those fields in any offensive scenarios.

Here's an example of a GetCellRoutine call in Windows 10, disassembled in IDA Pro:

And the same call in Windows 11:

Hive load failure information

This is a pointer to a public _HIVE_LOAD_FAILURE structure, which is passed as the first argument to the SetFailureLocation function every time an error occurs while loading a hive. It can be helpful in tracking which validity checks have failed for a given hive, without having to trace the entire loading process.

Base block

A pointer to a copy of the hive header, represented by the _HBASE_BLOCK structure.

Synchronization locks

There are two locks with the following purpose:

- FlusherLock – synchronizes access to the hive between clients changing data inside cells and the flusher thread;

- WriterLock – synchronizes access to the hive between writers that modify the bin/cell layout.

They are officially of type _CMSI_RW_LOCK, but they boil down to _EX_PUSH_LOCK, and they are used with standard kernel APIs such as ExAcquirePushLockSharedEx.

Dirty blocks information

Between offsets 0x58 and 0x84, _HHIVE stores several data structures representing the state of synchronization between the in-memory and on-disk instances of the hive.

Hive flags

First of all, there are two flags at offset 0x8C that indicate if the hive mapping is flat and if the hive is read-only. Secondly, there is a 32-bit HiveFlags member that stores further flags which aren't (as far as I know) included in any public Windows symbols. I have managed to reverse-engineer and infer the meaning of the constants I have observed, resulting in the following enum:

enum _HV_HIVE_FLAGS

{

HIVE_VOLATILE = 0x1,

HIVE_NOLAZYFLUSH = 0x2,

HIVE_PRELOADED = 0x10,

HIVE_IS_UNLOADING = 0x20,

HIVE_COMPLETE_UNLOAD_STARTED = 0x40,

HIVE_ALL_REFS_DROPPED = 0x80,

HIVE_ON_PRELOADED_LIST = 0x400,

HIVE_FILE_READ_ONLY = 0x8000,

HIVE_SECTION_BACKED = 0x20000,

HIVE_DIFFERENCING = 0x80000,

HIVE_IMMUTABLE = 0x100000,

HIVE_FILE_PAGES_MUST_BE_KEPT_LOCAL = 0x800000,

};

Below is a one-liner explanation of each flag:

- HIVE_VOLATILE: the hive exists in memory only; set, e.g., for \Registry and \Registry\Machine\HARDWARE.

- HIVE_NOLAZYFLUSH: changes to the hive aren't automatically flushed to disk and require a manual flush; set, e.g., for \Registry\Machine\SAM.

- HIVE_PRELOADED: the hive is one of the default, system ones; set, e.g., for \Registry\Machine\SOFTWARE, \Registry\Machine\SYSTEM, etc.

- HIVE_IS_UNLOADING: the hive is currently being loaded or unloaded in another thread and shouldn't be accessed before the operation is complete.

- HIVE_COMPLETE_UNLOAD_STARTED: the unloading process of the hive has started in CmpCompleteUnloadKey.

- HIVE_ALL_REFS_DROPPED: all references to the hive through KCBs have been dropped.

- HIVE_ON_PRELOADED_LIST: the hive is linked into a linked-list via the PreloadedHiveList field.

- HIVE_FILE_READ_ONLY: the underlying hive file is read-only and shouldn't be modified; indicates that the hive was loaded with the REG_OPEN_READ_ONLY flag set.

- HIVE_SECTION_BACKED: the hive is mapped in memory using section views.

- HIVE_DIFFERENCING: the hive is a differencing one (version 1.6, loaded under \Registry\WC).

- HIVE_IMMUTABLE: the hive is immutable and cannot be modified; indicates that it was loaded with the REG_IMMUTABLE flag set.

- HIVE_FILE_PAGES_MUST_BE_KEPT_LOCAL: the kernel always maintains a local copy of every page of the hive, either by locking it in physical memory or creating a private copy through the CoW mechanism.

Log file information

Between offsets 0xA4 to 0xCC, there are a number of fields having to do with log file management, i.e. the .LOG1/.LOG2 files accompanying the main hive file on disk.

Hive version

The Version field stores the minor version of the hive, which should theoretically be an integer between 3–6. However, as mentioned in the previous blog post, it is possible to set it to an arbitrary 32-bit value either by specifying a major version equal to 0 and any desired minor version, or by enticing the kernel to recover the hive header from a log file, and abusing the fact that the HvAnalyzeLogFiles function is more permissive than HvpGetHiveHeader. Nevertheless, I haven't found any security implications of this behavior.

View map

The view map holds all the essential information about how the hive is mapped in memory. The specific implementation of registry memory management has evolved considerably over the years, with its details changing between consecutive system versions. In the latest ones, the view map is represented by the top-level _HVP_VIEW_MAP public structure:

0: kd> dt _HVP_VIEW_MAP

nt!_HVP_VIEW_MAP

+0x000 SectionReference : Ptr64 Void

+0x008 StorageEndFileOffset : Int8B

+0x010 SectionEndFileOffset : Int8B

+0x018 ProcessTuple : Ptr64 _CMSI_PROCESS_TUPLE

+0x020 Flags : Uint4B

+0x028 ViewTree : _RTL_RB_TREE

The semantics of its respective fields are as follows:

- SectionReference: Contains a kernel-mode handle to a section object corresponding to the hive file, created via ZwCreateSection in CmSiCreateSectionForFile.

- StorageEndFileOffset: Stores the maximum size of the hive that can be represented with file-backed sections at any given time. Initially set to the size of the loaded hive, it can dynamically increase or decrease at runtime for mutable (normal) hives.

- SectionEndFileOffset: Represents the size of the hive file section at the time of loading. It is never modified past the first initialization in HvpViewMapStart, and seems to be mostly used as a safeguard against extending an immutable hive file beyond its original size.

- ProcessTuple: A structure of type _CMSI_PROCESS_TUPLE, it identifies the host process of the hive's section views. This field currently always points to the global CmpRegistryProcess object, which corresponds to the dedicated "Registry" process that hosts all hive mappings in the system. However, this field could enable a more fine-grained separation of hive mappings across multiple processes, should Microsoft choose to implement such a feature.

- Flags: Represents a set of memory management flags relevant to the entire hive. These flags are not publicly documented; however, through reverse engineering, I have determined their purpose to be as follows:

- VIEW_MAP_HIVE_FILE_IMMUTABLE (0x1): Indicates that the hive has been loaded as immutable, meaning no data is ever saved back to the underlying hive file.

- VIEW_MAP_MUST_BE_KEPT_LOCAL (0x2): Indicates that all of the hive data must be persistently stored in memory, and not just accessible through file-backed sections. This is likely to protect against double-fetch conditions involving hives loaded from remote network shares.

- VIEW_MAP_CONTAINS_LOCKED_PAGES (0x4): Indicates that some of the hive's pages are currently locked in physical memory using ZwLockVirtualMemory.

- ViewTree: This is the root of a view tree structure, which contains the descriptors of each continuous section view mapped in memory.

Overall, the implementation of low-level hive memory management in Windows is more complex than might initially seem necessary. This complexity arises from the kernel's need to gracefully handle a variety of corner cases and interactions. For example, hives may be loaded as immutable, which indicates that the hive may be operated on in memory, but changes must not be flushed to disk. Simultaneously, the system must support recovering data from .LOG files, including the possibility of extending the hive beyond its original on-disk length. At runtime, it must also be possible to efficiently modify the registry data, as well as shrink and extend it on demand. To further complicate matters, Windows enforces different rules for locking hive pages in memory depending on the backing volume of the file, carefully balancing optimal memory usage and system security guarantees. These and many other factors collectively contribute to the complexity of hive memory management.

To better understand how the view tree is organized, let's first analyze the general logic of the hive mapping code.

The hive mapping logic

The main kernel function responsible for mapping a hive in memory is HvLoadHive. It implements the overall logic and coordinates various sub-routines responsible for performing more specialized tasks, in the following order:

- Header Validation: The kernel reads and inspects the hive's header to ascertain its integrity, ensuring that the hive has not been tampered with or corrupted. Relevant function: HvpGetHiveHeader.

- Log Analysis: The kernel processes the hive's transaction logs, scrutinising them to identify any pending changes or inconsistencies that necessitate recovery procedures. Relevant function: HvAnalyzeLogFiles.

- Initial Section Mapping: A section object is created based on the hive file, and further segmented into multiple views, each aligned to 4 KiB boundaries and capped at 2 MiB. At this point, the kernel prioritizes the creation of an initial mapping without focusing on the granular layout of individual bins within the hive. Relevant function: HvpViewMapStart.

- Cell Map Initialization: The cell map, a component that translates cell indexes to memory address, is initialized. Its entries are configured to point to the newly created views. Relevant function: HvpMapHiveImageFromViewMap.

- Log Recovery (if required): If the preceding log analysis reveals the need for data recovery, the kernel attempts to restore data integrity. This is the earliest point at which the newly created memory mappings may already be modified and marked as "dirty", indicating that their contents have been altered and require synchronisation with the on-disk representation. Relevant function: HvpPerformLogFileRecovery.

- Bin Mapping: In this final stage, the kernel establishes definitive memory mappings for each bin within the hive, ensuring that each bin occupies a contiguous region of memory. This process may necessitate creating new views, eliminating existing ones, or adjusting their boundaries to accommodate the specific arrangement of bins. Relevant function: HvpRemapAndEnlistHiveBins.

Now that we understand the primary components of the loading process, we can examine the internal structure of the section view tree in more detail.

The view tree

Let's consider an example hive consisting of three bins of sizes 256 KiB, 2 MiB and 128 KiB, respectively. After step 3 ("Initial Section Mapping"), the section views created by the kernel are as follows:

As we can see, at this point, the kernel doesn't concern itself with bin boundaries or continuity: all it needs to achieve is to make every page of the hive accessible through a section view for log recovery purposes. In simple terms, the way that HvpViewMapStart (or more specifically, HvpViewMapCreateViewsForRegion) works is it creates as many 2 MiB views as necessary, followed by one last view that covers the remaining part of the file. So in our example, we have the first view that covers bin 1 and the beginning of bin 2, and the second view that covers the trailing part of bin 2 and the entire bin 3. It's important to note that memory continuity is only guaranteed within the scope of a single view, and views 1 and 2 may be mapped at completely different locations in the virtual address space.

Later in step 6, the system ensures that every bin is mapped as a contiguous block of memory before handing off the hive to the client. This is done by iterating through all the bins, and for every bin that spans more than one view in the current view map, the following operations are performed:

- If the start and/or the end of the bin fall into the middle of existing views, these views are truncated from either side. Furthermore, if there are any views that are fully covered by the bin, they are freed and removed from the tree.

- A new, dedicated section view is created for the bin and inserted into the view tree.

In our hypothetical scenario, the resulting view layout would be as follows:

As we can see, the kernel shrinks views 1 and 2, and creates a new view 3 corresponding to bin 2 to fill the gap. The final layout of the binary tree of section view descriptors is illustrated below:

Knowing this, we can finally examine the structure of a single view tree entry. It is not included in the public symbols, but I named it _HVP_VIEW. My reverse-engineered version of its definition is as follows:

struct _HVP_VIEW

{

RTL_BALANCED_NODE Node;

LARGE_INTEGER ViewStartOffset;

LARGE_INTEGER ViewEndOffset;

SSIZE_T ValidStartOffset;

SSIZE_T ValidEndOffset;

PBYTE MappingAddress;

SIZE_T LockedPageCount;

_HVP_VIEW_PAGE_FLAGS PageFlags[];

};

The role of each particular field is documented below:

- Node: This is the structure used to link all of the entries into a single red-black tree, passed to helper kernel functions such as RtlRbInsertNodeEx and RtlRbRemoveNode.

- ViewStartOffset and ViewEndOffset: This offset pair specifies the overall byte range covered by the underlying section view object in the hive file. Their difference corresponds to the cumulative length of the red and green boxes in a single row in the diagrams above.

- ValidStartOffset and ValidEndOffset: This offset pair specifies the valid range of the hive accessible through this view, i.e. the green rectangles in the diagrams. It must always be a subset of the [ViewStartOffset, ViewEndOffset] range, and may dynamically change while re-mapping bins (as just shown in this section), as well as when shrinking and extending the hive.

- MappingAddress: This is the base address of the section view mapping in memory, as returned by ZwMapViewOfSection. It is valid in the context of the process specified by _HVP_VIEW_MAP.ProcessTuple (currently always the "Registry" process). It covers the entire range between [ViewStartOffset, ViewEndOffset], but only pages between [ValidStartOffset, ValidEndOffset] are accessible, and the rest of the section view is marked as PAGE_NOACCESS.

- LockedPageCount: Specifies the number of pages locked in virtual memory using ZwLockVirtualMemory within this view.

- PageFlags: A variable-length array that specifies a set of flags for each memory page in the [ViewStartOffset, ViewEndOffset] range.

I haven't found any (un)official sources documenting the set of supported page flags, so below is my attempt to name them and explain their meaning:

|

Flag |

Value |

Description |

|

VIEW_PAGE_VALID |

0x1 |

Indicates if the page is valid – true for pages between [ValidStartOffset, ValidEndOffset], false otherwise. If this flag is clear, all other flags are irrelevant/unused. The flag is set:

The flag is cleared:

|

|

VIEW_PAGE_COW_BY_CALLER |

0x2 |

Indicates if the kernel maintains a copy of the page through the copy-on-write (CoW) mechanism, as initiated by a client action, e.g. a registry operation that modified data in a cell and thus resulted in marking the page as dirty. The flag is set:

The flag is cleared:

|

|

VIEW_PAGE_COW_BY_POLICY |

0x4 |

Indicates if the kernel maintains a copy of the page through the copy-on-write (CoW) mechanism, as required by the policy that all pages of non-local hives (hives loaded from volumes other than the system volume) must always remain in memory. The flag is set:

The flag is cleared:

|

|

VIEW_PAGE_WRITABLE |

0x8 |

Indicates if the page is currently marked as writable, typically as a result of a modifying operation on the page that hasn't been yet flushed to disk. The flag is set:

The flag is cleared:

|

|

VIEW_PAGE_LOCKED |

0x10 |

Indicates if the page is currently locked in physical memory. The flag is set:

The flag is cleared:

|

The semantics of most of the flags are straightforward, but perhaps VIEW_PAGE_COW_BY_POLICY and VIEW_PAGE_LOCKED warrant a slightly longer explanation. The two flags are mutually exclusive, and they represent nearly identical ways to achieve the same goal: ensure that a copy of each hive page remains resident in memory or a pagefile. Under normal circumstances, the kernel could simply create the necessary section views in their default form, and let the memory management subsystem decide how to handle their pages most efficiently. However, one of the guarantees of the registry is that once a hive has been loaded, it must remain operational for as long as it is active in the system. On the other hand, section views have the property that (parts of) their underlying data may be completely evicted by the kernel, and later re-read from the original storage medium such as the hard drive. So, it is possible to imagine a situation where:

- A hive is loaded from a removable drive (e.g. a CD-ROM or flash drive) or a network share,

- Due to high memory pressure from other applications, some of the hive pages are evicted from memory,

- The removable drive with the hive file is ejected from the system,

- A client subsequently tries to operate on the hive, but parts of it are unavailable and cannot be fetched again from the original source.

This could cause some significant problems and make the registry code fail in unexpected ways. It would also constitute a security vulnerability: the kernel assumes that once it has opened and sanitized the hive file, its contents remain consistent for as long as the hive is used. This is achieved by opening the file with exclusive access, but if the hive data was ever re-read by the Windows memory manager, a malicious removable drive or an attacker-controlled network share could ignore the exclusivity request and provide different, invalid data on the second read. This would result in a kind of "double fetch" condition and potentially lead to kernel memory corruption.

To address both the reliability and security concerns, Windows makes sure to never evict pages corresponding to hives for which exclusive access cannot be guaranteed. This covers hives loaded from a location other than the system volume, and since Windows 10 19H1, also all app hives regardless of the file location. The first way to achieve this is by locking the pages directly in physical memory with a ZwLockVirtualMemory call. It is used for the initial ≤ 2 MiB section views created while loading a hive, up to the working set limit of the Registry process currently set at 64 MiB. The second way is by taking advantage of the copy-on-write mechanism – that is, marking the relevant pages as PAGE_WRITECOPY and subsequently touching each of them using the HvpViewMapTouchPages helper function. This causes the memory manager to create a private copy of each memory page containing the same data as the original, thus preventing them from ever being unavailable for registry operations.

Between the two types of resident pages, the CoW type effectively becomes the default option in the long term. Eventually most pages converge to this state, even if they initially start as locked. This is because locked pages transition to CoW on multiple occasions, e.g. when converted by the background CmpDoLocalizeNextHive thread that runs every 60 seconds, or during the modification of a cell. On the other hand, once a page transitions to the CoW state, it never reverts to being locked. A diagram illustrating the transitions between the page residence states in a hive loaded from removable/remote storage is shown below:

For normal hives loaded from the system volume (i.e. without the VIEW_MAP_MUST_BE_KEPT_LOCAL flag set), the state machine is much simpler:

As a side note, CVE-2024-43452 was an interesting bug that exploited a flaw in the page residency protection logic. The bug arose because some data wasn't guaranteed to be resident in memory and could be fetched twice from a remote SMB share during bin mapping. This occurred early in the hive loading process, before page residency protections were fully in place. The kernel trusted the data from the second read without re-validation, allowing it to be maliciously set to invalid values, resulting in kernel memory corruption.

Cell maps

As discussed in Part 5, almost every cell contains references to other cells in the hive in the form of cell indexes. Consequently, virtually every registry operation involves multiple rounds of translating cell indexes into their corresponding virtual addresses in order to traverse the registry structure. Section views are stored in a red-black tree, so the search complexity is O(log n). This may seem decent, but if we consider that on a typical system, the registry is read much more often than it is extended/shrunk, it becomes apparent that it makes sense to further optimize the search operation at the cost of a less efficient insertion/deletion. And this is exactly what cell maps are: a way of trading a faster search complexity of O(1) for slower insertion/deletion complexity of O(n) instead of O(log n). Thanks to this technique, HvpGetCellPaged – perhaps the hottest function in the Windows registry implementation – executes in constant time.

In technical terms, cell maps are pagetable-like structures that divide the 32-bit hive address space into smaller, nested layers consisting of so-called directories, tables, and entries. As a reminder, the layout of cell indexes and cell maps is illustrated in the diagram below, based on a similar diagram in the Windows Internals book, which itself draws from Mark Russinovich's 1999 article, Inside the Registry:

Given the nature of the data structure, the corresponding cell map walk involves dereferencing three nested arrays based on the subsequent 1, 10 and 9-bit parts of the cell index, and then adding the final 12-bit offset to the page-aligned address of the target block. The internal kernel structures matching the respective layers of the cell map are _DUAL, _HMAP_DIRECTORY, _HMAP_TABLE and _HMAP_ENTRY, all publicly accessible via the ntoskrnl.exe PDB symbols. The entry point to the cell map is the Storage array at the end of the _HHIVE structure:

0: kd> dt _HHIVE

nt!_HHIVE

[...]

+0x118 Storage : [2] _DUAL

The index into the two-element array represents the storage type, 0 for stable and 1 for volatile, so a single _DUAL structure describes a 2 GiB view of a specific storage space:

0: kd> dt _DUAL

nt!_DUAL

+0x000 Length : Uint4B

+0x008 Map : Ptr64 _HMAP_DIRECTORY

+0x010 SmallDir : Ptr64 _HMAP_TABLE

+0x018 Guard : Uint4B

+0x020 FreeDisplay : [24] _FREE_DISPLAY

+0x260 FreeBins : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x270 FreeSummary : Uint4B

Let's examine the semantics of each field:

- Length: Expresses the current length of the given storage space in bytes. Directly after loading the hive, the stable length is equal to the size of the hive on disk (including any data recovered from log files, minus the 4096 bytes of the header), and the volatile space is empty by definition. Only cell map entries within the [0, Length - 1] range are guaranteed to be valid.

- Map: Points to the actual directory structure represented by _HMAP_DIRECTORY.

- SmallDir: Part of the "small dir" optimization, discussed in the next section.

- Guard: Its specific role is unclear, as the field is always initialized to 0xFFFFFFFF upon allocation and never used afterwards. I expect that it is some kind of debugging remnant from the early days of the registry development, presumably related to the small dir optimization.

- FreeDisplay: A data structure used to optimize searches for free cells during the cell allocation process. It consists of 24 buckets, each corresponding to a specific cell size range and represented by the _FREE_DISPLAY structure, indicating which pages in the hive may potentially contain free cells of the given length.

- FreeBins: The head of a doubly-linked list that links the descriptors of entirely empty bins in the hive, represented by the _FREE_HBIN structures.

- FreeSummary: A bitmask indicating which buckets within FreeDisplay have any hints set for the given cell size. A zero bit at a given position means that there are no free cells of the specific size range anywhere in the hive.

The next level in the cell map hierarchy is the _HMAP_DIRECTORY structure:

0: kd> dt _HMAP_DIRECTORY

nt!_HMAP_DIRECTORY

+0x000 Directory : [1024] Ptr64 _HMAP_TABLE

As we can see, it is simply a 1024-element array of pointers to _HMAP_TABLE:

0: kd> dt _HMAP_TABLE

nt!_HMAP_TABLE

+0x000 Table : [512] _HMAP_ENTRY

Further, we get a 512-element array of pointers to the final level of the cell map, _HMAP_ENTRY:

0: kd> dt _HMAP_ENTRY

nt!_HMAP_ENTRY

+0x000 BlockOffset : Uint8B

+0x008 PermanentBinAddress : Uint8B

+0x010 MemAlloc : Uint4B

This last level contains a descriptor of a single page in the hive and warrants a deeper analysis. Let's start by noting that the four least significant bits of PermanentBinAddress correspond to a set of undocumented flags that control various aspects of the page behavior. I was able to reverse-engineer them and partially recover their names, largely thanks to the fact that some older Windows 10 builds contained non-inlined functions operating on these flags, with revealing names like HvpMapEntryIsDiscardable or HvpMapEntryIsTrimmed:

enum _MAP_ENTRY_FLAGS

{

MAP_ENTRY_NEW_ALLOC = 0x1,

MAP_ENTRY_DISCARDABLE = 0x2,

MAP_ENTRY_TRIMMED = 0x4,

MAP_ENTRY_DUMMY = 0x8,

};

Here's a brief summary of their meaning based on my understanding:

- MAP_ENTRY_NEW_ALLOC: Indicates that this is the first page of a bin. Cell indexes pointing into this page must specify an offset within the range of [0x20, 0xFFF], as they cannot fall into the first 32 bytes that correspond to the _HBIN structure.

- MAP_ENTRY_DISCARDABLE: Indicates that the whole bin is empty and consists of a single free cell.

- MAP_ENTRY_TRIMMED: Indicates that the page has been marked as "trimmed" in HvTrimHive. More specifically, this property is related to hive reorganization, and is set during the loading process on some number of trailing pages that only contain keys accessed during boot, or not accessed at all since the last reorganization. The overarching goal is likely to prevent introducing unnecessary fragmentation in the hive by avoiding mixing together keys with different access histories.

- MAP_ENTRY_DUMMY: Indicates that the page is allocated from the kernel pool and isn't part of a section view.

With this in mind, let's dive into the details of each _HMAP_ENTRY structure member:

- PermanentBinAddress: The lower 4 bits contain the above flags. The upper 60 bits represent the base address of the bin mapping corresponding to this page.

- BlockOffset: This field has a dual functionality. If the MAP_ENTRY_DISCARDABLE flag is set, it is a pointer to a descriptor of a free bin, _FREE_HBIN, linked into the _DUAL.FreeBins linked list. If it is clear (the typical case), it expresses the offset of the page relative to the start of the bin. Therefore, the virtual address of the block's data in memory can be calculated as (PermanentBinAddress & (~0xF)) + BlockOffset.

- MemAlloc: If the MAP_ENTRY_NEW_ALLOC flag is set, it contains the size of the bin, otherwise it is zero.

And this concludes the description of how cell maps are structured. Taking all of it into account, the implementation of the HvpGetCellPaged function starts to make a lot of sense. Its pseudocode comes down to the following:

_CELL_DATA *HvpGetCellPaged(_HHIVE *Hive, HCELL_INDEX Index) {

_HMAP_ENTRY *Entry = &Hive->Storage[Index >> 31].Map

->Directory[(Index >> 21) & 0x3FF]

->Table[(Index >> 12) & 0x1FF];

return (Entry->PermanentBinAddress & (~0xF)) + Entry->BlockOffset + (Index & 0xFFF) + 4;

}

The same process is followed, for example, by the implementation of the WinDbg !reg cellindex extension, which also translates a pair of a hive pointer and a cell index into the virtual address of the cell.

The small dir optimization

There is one other implementation detail about the cell maps worth mentioning here – the small dir optimization. Let's start with the observation that a majority of registry hives in Windows are relatively small, below 2 MiB in size. This can be easily verified by using the !reg hivelist command in WinDbg, and taking note of the values in the "Stable Length" and "Volatile Length" columns. Most of them usually contain values between several kilobytes to hundreds of kilobytes. This would mean that if the kernel allocated the full first-level directory for these hives (taking up 1024 entries × 8 bytes = 8 KiB on 64-bit platforms), they would still only use the first element in it, leading to a non-trivial waste of memory – especially in the context of the early 1990's when the registry was first implemented. In order to optimize this common scenario, Windows developers employed an unconventional approach to simulate a 1-item long "array" with the SmallDir member of type _HMAP_TABLE in the _DUAL structure, and have the _DUAL.Map pointer point at it instead of a separate pool allocation when possible. Later, whenever the hive grows and requires more than one element of the cell map directory, the kernel falls back to the standard behavior and performs a normal pool allocation for the directory array.

A revised diagram illustrating the cell map layout of a small hive is shown below:

Here, we can see that indexes 1 through 1023 of the directory array are invalid. Instead of correctly initialized _HMAP_TABLE structures, they point into "random" data corresponding to other members of the _DUAL and the larger _CMHIVE structure that happen to be located after _DUAL.SmallDir. Ordinarily, this is merely a low-level detail that doesn't have any meaningful implications, as all actively loaded hives remain internally consistent and always contain cell indexes that remain within the bounds of the hive's storage space. However, if we look at it through the security lens of hive-based memory corruption, this behavior suddenly becomes very interesting. If an attacker was able to implant an out-of-bounds cell index with the directory index greater than 0 into a hive, they would be able to get the kernel to operate on invalid (but deterministic) data as part of the cell map walk, and enable a powerful arbitrary read/write primitive. In addition to the small dir optimization, this technique is also enabled by the fact that the HvpGetCellPaged routine doesn't perform any bounds checks of the cell indexes, instead blindly trusting that they are always valid.

If you are curious to learn more about the exploitation aspect of out-of-bounds cell indexes, it was the main subject of my Practical Exploitation of Registry Vulnerabilities in the Windows Kernel talk given at OffensiveCon 2024 (slides and video recording are available). I will also discuss it in more detail in one of the future blog posts focused specifically on the security impact of registry vulnerabilities.

_CMHIVE structure overview

Beyond the first member of type _HHIVE at offset 0, the _CMHIVE structure contains more than 3 KiB of further information describing an active hive. This data relates to concepts more abstract than memory management, such as the registry tree structure itself. Below, instead of a field-by-field analysis, we'll focus on the general categories of information within _CMHIVE, organized loosely by increasing complexity of the data structures:

- Reference count: a 32-bit refcount primarily used during short-term operations on the hive, to prevent the object from being freed while actively operated on. These are used by the thin wrappers CmpReferenceHive and CmpDereferenceHive.

- File handles and sizes: handles and current sizes of the hive files on disk, such as the main hive file (.DAT) and the accompanying log files (.LOG, .LOG1, .LOG2). The handles are stored in FileHandles array, and the sizes reside in ActualFileSize and LogFileSizes.

- Text strings: some informational strings that may prove useful when trying to identify a hive based on its _CMHIVE structure. For example, the hive file name is stored in FileUserName, and the hive mount point path is stored in HiveRootPath.

- Timestamps: there are several timestamps that can be found in the hive descriptor, such as DirtyTime, UnreconciledTime or LastWriteTime.

- List entries: instances of the _LIST_ENTRY structure used to link the hive into various double-linked lists, such as the global list of hives in the system (HiveList, starting at nt!CmpHiveListHead), or the list of hives within a common trust class (TrustClassEntry).

- Synchronization mechanisms: various objects used to synchronize access to the hive as a whole, or some of its parts. Examples include HiveRundown, SecurityLock and HandleClosePendingEvent.

- Unload history: a 128-element array that stores the number of steps that have been successfully completed in the process of unloading the hive. Its specific purpose is unclear, it might be a debugging artifact retained from older versions of Windows.

- Late unload state: objects related to deferred unloading of registry hives (LateUnloadWorkItemState, LateUnloadFinishedEvent, LateUnloadWorkItem).

- Hive layout information: the hive reorganization process in Windows tries to optimize hives by grouping together keys accessed during system runtime, followed by keys accessed during system boot, followed by completely unused keys. If a hive is structured according to this order during load, the kernel saves information about the boundaries between the three distinct areas in the BootStart, UnaccessedStart and UnaccessedEnd members of _CMHIVE.

- Flushing state and dirty block information: any state that has to do with marking cells as dirty and synchronizing their contents to disk. There are a significant number of fields related to the functionality, with names starting with "Flush...", "Unreconciled..." and "CapturedUnreconciled...".

- Volume context: a pointer to a public _CMP_VOLUME_CONTEXT structure, which provides extended information about the disk volume of the hive file. As an example, it is used in the internal CmpVolumeContextMustHiveFilePagesBeKeptLocal routine to determine whether the volume is a system one, and consequently whether certain security/reliability assumptions are guaranteed for it or not.

- KCB table and root KCB: a table of the globally visible KCB (Key Control Block) structures corresponding to keys in the hive, and a pointer to the root key's KCB. I will discuss KCBs in more detail in the "Key structures" section below.

- Security descriptor cache: a cache of all security descriptors present in the hive, allocated from the kernel pool and thus accessible more efficiently than the underlying hive mappings. In my bug reports, I have often taken advantage of the security cache as a straightforward way to demonstrate the exploitability of security descriptor use-after-frees. A security node UAF can be easily converted into an UAF of its pool-based cached object, which then reliably triggers a Blue Screen of Death when Special Pool is enabled. The security cache of any given hive can be enumerated using the !reg seccache command in WinDbg.

- Transaction-related objects: a pointer to a _CM_RM structure that describes the Resource Manager object associated with the hive, if "heavyweight" transactions (i.e. KTM transactions) are enabled for it.

Last but not least, _CMHIVE has its own Flags field that is different from _HHIVE.Flags. As usual, the flags are not documented, so the listing below is a product of my own analysis:

enum _CM_HIVE_FLAGS

{

CM_HIVE_UNTRUSTED = 0x1,

CM_HIVE_IN_SID_MAPPING_TABLE = 0x2,

CM_HIVE_HAS_RM = 0x8,

CM_HIVE_IS_VIRTUALIZABLE = 0x10,

CM_HIVE_APP_HIVE = 0x20,

CM_HIVE_PROCESS_PRIVATE = 0x40,

CM_HIVE_MUST_BE_REORGANIZED = 0x400,

CM_HIVE_DIFFERENCING_WRITETHROUGH = 0x2000,

CM_HIVE_CLOUDFILTER_PROTECTED = 0x10000,

};

A brief description of each of them is as follows:

- CM_HIVE_UNTRUSTED: the hive is "untrusted" in the sense of registry symbolic links; in other words, it is not one of the default system hives loaded on boot. The distinction is that trusted hives can freely link to all other hives in the system, while untrusted ones can only link to hives within their so-called trust class. This is to prevent confused deputy-style privilege escalation attacks in the system.

- CM_HIVE_IN_SID_MAPPING_TABLE: the hive is linked into an internal data structure called the "SID mapping table" (nt!CmpSIDToHiveMapping), used to efficiently look up the user class hives mounted at \Registry\User\<SID>_Classes for the purposes of registry virtualization.

- CM_HIVE_HAS_RM: KTM transactions are enabled for this hive, meaning that the corresponding .blf and .regtrans-ms files are present in the same directory as the main hive file. The flag is clear if the hive is an app hive or if it was loaded with the REG_HIVE_NO_RM flag set.

- CM_HIVE_IS_VIRTUALIZABLE: accesses to this hive may be subject to registry virtualization. As far as I know, the only hive with this flag set is currently HKLM\SOFTWARE, which seems in line with the official documentation.

- CM_HIVE_APP_HIVE: this is an app hive, i.e. it was loaded under \Registry\A with the REG_APP_HIVE flag set.

- CM_HIVE_PROCESS_PRIVATE: this hive is private to the loading process, i.e. it was loaded with the REG_PROCESS_PRIVATE flag set.

- CM_HIVE_MUST_BE_REORGANIZED: the hive fragmentation threshold (by default 1 MiB) has been exceeded, and the hive should undergo the reorganization process at the next opportunity. The flag is simply a means of communication between the CmCheckRegistry and CmpReorganizeHive internal routines, both of which execute during hive loading.

- CM_HIVE_DIFFERENCING_WRITETHROUGH: this is a delta hive loaded in the writethrough mode, which technically means that the DIFF_HIVE_WRITETHROUGH flag was specified in the DiffHiveFlags member of the VRP_LOAD_DIFFERENCING_HIVE_INPUT structure, as discussed in Part 4.

- CM_HIVE_CLOUDFILTER_PROTECTED: new flag added in December 2024 as part of the fix for CVE-2024-49114. It indicates that the hive file has been protected against being converted to a Cloud Filter placeholder by setting the "$Kernel.CFDoNotConvert" extended attribute (EA) on the file in CmpAdjustFileCFSafety.

This concludes the documentation of the hive descriptor structure, arguably the largest and most complex object in the Windows registry implementation.

Key structures

The second most important objects in the registry are keys. They can be basically thought of as the essence of the registry, as nearly every registry operation involves them in some way. They are also the one and only registry element that is tightly integrated with the Windows NT Object Manager. This comes with many benefits, as client applications can operate on the registry using standardized handles, and can leverage automatic security checks and object lifetime management. However, this integration also presents its own challenges, as it requires the Configuration Manager to interact with the Object Manager correctly and handle its intricacies and edge cases securely. For this reason, internal key-related structures play a crucial role in the registry implementation. They help organize key state in a way that simplifies keeping it up-to-date and internally consistent. For security researchers, understanding these structures and their semantics is invaluable. This knowledge enables you to quickly identify bugs in existing code or uncover missing handling of unusual but realistic conditions.

The two fundamental key structures in the Windows kernel are the key body (_CM_KEY_BODY) and key control block (_CM_KEY_CONTROL_BLOCK). The key body is directly associated with a key handle in the NT Object Manager, similar to the role that the _FILE_OBJECT structure plays for file handles. In other words, this is the initial object that the kernel obtains whenever it calls ObReferenceObjectByHandle to reference a user-supplied handle. There may concurrently exist a number of key body structures associated with a single key, as long as there are several programs holding active handles to the key. Conversely, the key control block represents the global state of a specific key and is used to manage its general properties. This means that for most keys in the system, there is at most one KCB allocated at a time. There may be no KCB for keys that haven't been accessed yet (as they are initialized by the kernel lazily), and there may be more than one KCB for the same registry path if the key has been deleted and created again (these two instances of the key are treated as separate entities, with one of them being marked as deleted/non-existent). Taking this into account, the relationship between key bodies and KCBs is many-to-one, with all of the key bodies of a single KCB being connected in a doubly-linked list, as shown in the diagram below:

The following subsections provide more detail about each of these two structures.

Key body

The key body structure is allocated and initialized in the internal CmpCreateKeyBody routine, and freed by the NT Object Manager when all references to the object are dropped. It is a relatively short and simple object with the following definition:

0: kd> dt _CM_KEY_BODY

nt!_CM_KEY_BODY

+0x000 Type : Uint4B

+0x004 AccessCheckedLayerHeight : Uint2B

+0x008 KeyControlBlock : Ptr64 _CM_KEY_CONTROL_BLOCK

+0x010 NotifyBlock : Ptr64 _CM_NOTIFY_BLOCK

+0x018 ProcessID : Ptr64 Void

+0x020 KeyBodyList : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x030 Flags : Pos 0, 16 Bits

+0x030 HandleTags : Pos 16, 16 Bits

+0x038 Trans : _CM_TRANS_PTR

+0x040 KtmUow : Ptr64 _GUID

+0x048 ContextListHead : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x058 EnumerationResumeContext : Ptr64 Void

+0x060 RestrictedAccessMask : Uint4B

+0x064 LastSearchedIndex : Uint4B

+0x068 LockedMemoryMdls : Ptr64 Void

Let's quickly go over each field:

- Type: for normal keys (i.e. almost all of them), this field is set to a magic value of 0x6B793032 ('ky02'). However, for predefined keys, this is the 32-bit value of the link's target key with the highest bit set. This member is therefore used to distinguish between regular keys and predefined ones, for example in CmObReferenceObjectByHandle. Predefined keys have been now largely deprecated, but it is still possible to observe a non-standard Type value by opening a handle to one of the two last remaining ones: HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Perflib\009 and CurrentLanguage under the same path.

- AccessCheckedLayerHeight: a new field added in November 2023 as part of the fix for CVE-2023-36404. It is used for layered keys and contains the index of the lowest layer in the key stack that was access-checked when opening the key. It is later taken into account during other registry operations, in order to avoid leaking data from lower-layer, more restrictive keys that could have been created since the handle was opened.

- KeyControlBlock: a pointer to the corresponding key control block.

- NotifyBlock: an optional pointer to the notify block associated with this handle. This is related to the key notification functionality in Windows and is described in more detail in the "Key notification structures" section below.

- ProcessID: the PID of the process that created the handle. It doesn't seem to serve any purpose in the kernel other than to be enumerable using the NtQueryOpenSubKeysEx system call (which requires SeRestorePrivilege, and is therefore available to administrators only).

- KeyBodyList: the list entry used to link all the key bodies within a single KCB together.

- Flags: a set of flags concerning the specific key body. Here's my interpretation of them based on reverse engineering:

- KEY_BODY_HIVE_UNLOADED (0x1): indicates that the underlying hive of the key has been unloaded and is no longer active.

- KEY_BODY_DONT_RELOCK (0x2): this seems to be a short-term flag used to communicate between CmpCheckKeyBodyAccess/CmpCheckOpenAccessOnKeyBody and the nested CmpDoQueryKeyName routine, in order to indicate that the key's KCB is already locked and shouldn't be relocked again.

- KEY_BODY_DONT_DEINIT (0x4): if this flag is set, CmpDeleteKeyObject returns early and doesn't proceed with the regular deinitialization of the key body object. However, it is unclear if/where the flag is set in the code, as I personally haven't found any instances of it happening during my analysis.

- KEY_BODY_DELETED (0x8): indicates that the key has been deleted since the handle was opened, and it no longer exists.

- KEY_BODY_DONT_VIRTUALIZE (0x10): indicates that registry virtualization is disabled for this handle, as a result of opening the key with the (undocumented but present in SDK headers) REG_OPTION_DONT_VIRTUALIZE flag.

- HandleTags: from the kernel perspective, this is simply a general purpose 16-bit storage that can be set by clients on a per-handle basis using NtSetInformationKey with the KeySetHandleTagsInformation information class, and queried with NtQueryKey and the KeyHandleTagsInformation information class. As far as I know, the kernel doesn't dictate how this field should be used and leaves it up to the registry clients. In practice, it seems to be mostly used for purposes related to WOW64 and the Registry Redirector, storing flags such as KEY_WOW64_64KEY (0x100) and KEY_WOW64_32KEY (0x200), as well as some internal ones. The WOW64 functionality is implemented in KernelBase.dll, and functions such as ConstructKernelKeyPath and LocalBaseRegOpenKey are a good starting point for reverse engineering, if you're curious to learn more. I have also observed the 0x1000 handle tag being set in the internal IopApplyMutableTagToRegistryKey kernel routine for keys such as HKLM\System\ControlSet001\Control\Class\{4D36E968-E325-11CE-BFC1-08002BE10318}\0000, but I'm unsure of its meaning.

- Trans: Indicates the transactional state of the handle. If the handle is not transacted (i.e. it wasn't opened with one of RegOpenKeyTransacted or RegCreateKeyTransacted), it is set to zero. Otherwise, the lowest bit specifies the type of the transaction: 0 for KTM and 1 for lightweight transactions. The remaining bits form a pointer to the associated transaction object, either of the TmTransactionObjectType type (represented by the _KTRANSACTION structure), or of the CmRegistryTransactionType type (represented by a non-public structure that I've personally named _CM_LIGHTWEIGHT_TRANS_OBJECT).

- KtmUow: if the handle is associated with a KTM transaction, this field stores the GUID that uniquely identifies it. For non-transacted and lightweight-transacted handles, the field is unused.

- ContextListHead: this is the head of the doubly-linked list of contexts that have been associated with the key body using the CmSetCallbackObjectContext function. It is related to the registry callbacks functionality; see also the Specifying Context Information MSDN article for more details.

- EnumerationResumeContext: this is part of an optimization of the subkey enumeration process of layered keys (implemented in CmpEnumerateLayeredKey). Performing full enumeration of a layered key from scratch up to the given index is a very complex task, and repeating it over and over for each iteration of an enumeration loop would be very inefficient. The resume context helps address the problem for sequential enumeration by saving the intermediate state reached at an NtEnumerateKey call with a given index, and being able to resume from it when a request for index+1 comes next. It also has the added benefit of making it possible to stop and restart the enumeration process in the scope of a single system call, which is used to pause the operation and temporarily release some locks if the code detects that the registry is particularly congested. This happens at the intersection of the CmEnumerateKey and CmpEnumerateLayeredKey functions, with the latter potentially returning STATUS_RETRY and the former resuming the operation if such a situation arises.

- RestrictedAccessMask, LastSearchedIndex, LockedMemoryMdls: relatively new fields introduced in Windows 10 and 11, which I haven't looked very deeply into and thus won't discuss in detail here.

After a key handle is translated into the corresponding _CM_KEY_BODY structure using the ObReferenceObjectByHandle(CmKeyObjectType) call, typically early in the execution of a registry-related system call, there are three primary operations that are usually performed. First, the kernel does a key status check by evaluating the expression KeyBody.Flags & 9 to determine if the key is associated with an unloaded hive (flag 0x1) or has been deleted (flag 0x8). This check is essential because most registry operations are only permitted on active, existing keys, and enforcing this condition is a fundamental step for guaranteeing registry state consistency. Second, the code accesses the KeyControlBlock pointer, which provides further access to the hive pointer (KCB.KeyHive), the key's cell index (KCB.KeyCell), and other necessary fields and data structures required to perform any meaningful read/write actions on the key. Finally, the code checks the key body's Trans/KtmUow members to determine if the handle is part of a transaction, and if so, the transaction is used as additional context for the action requested by the caller. Accesses to other members of the _CM_KEY_BODY structure are less frequent and serve more specialized purposes.

Key control block

The key control block object can be thought of as the heart of the Windows kernel registry tree representation. It is effectively the descriptor of a single key in the system, and the second most important key-related object after the key node. It is always allocated from the kernel pool, and serves four main purposes:

- Mirrors frequently used information from the key node to make it faster to access by the kernel code. This includes building an efficient, in-memory representation of the registry tree to optimize the traversal time when referring to registry paths.

- Works as a single point of reference for all active handles to a specific key, and helps synchronize access to the key in the multithreaded Windows environment.

- Represents any pending, transacted state of the registry key that has been introduced by a client, but not fully committed yet.

- Represents any complex relationships between registry keys that extend beyond the internal structure of the hive. The primary example are differencing hives, which are overlaid on top of each other, and whose corresponding keys form so-called key stacks.

Blog post #2 in this series highlighted the dramatic growth of the registry codebase across successive Windows versions, illustrating the subsystem's steady expansion over the last few decades. Similarly, the size of the Key Control Block (KCB) itself has nearly doubled in time, from 168 bytes in Windows XP x64 to 312 bytes in the latest Windows 11 release. This expansion underscores the increasing amount of information associated with every registry key, which the kernel must manage consistently and securely.

The KCB structure layout is present in the PDB symbols and can be displayed in WinDbg:

0: kd> dt _CM_KEY_CONTROL_BLOCK

nt!_CM_KEY_CONTROL_BLOCK

+0x000 RefCount : Uint8B

+0x008 ExtFlags : Pos 0, 16 Bits

+0x008 Freed : Pos 16, 1 Bit

+0x008 Discarded : Pos 17, 1 Bit

+0x008 HiveUnloaded : Pos 18, 1 Bit

+0x008 Decommissioned : Pos 19, 1 Bit

+0x008 SpareExtFlag : Pos 20, 1 Bit

+0x008 TotalLevels : Pos 21, 10 Bits

+0x010 KeyHash : _CM_KEY_HASH

+0x010 ConvKey : _CM_PATH_HASH

+0x018 NextHash : Ptr64 _CM_KEY_HASH

+0x020 KeyHive : Ptr64 _HHIVE

+0x028 KeyCell : Uint4B

+0x030 KcbPushlock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x038 Owner : Ptr64 _KTHREAD

+0x038 SharedCount : Int4B

+0x040 DelayedDeref : Pos 0, 1 Bit

+0x040 DelayedClose : Pos 1, 1 Bit

+0x040 Parking : Pos 2, 1 Bit

+0x041 LayerSemantics : UChar

+0x042 LayerHeight : Int2B

+0x044 Spare1 : Uint4B

+0x048 ParentKcb : Ptr64 _CM_KEY_CONTROL_BLOCK

+0x050 NameBlock : Ptr64 _CM_NAME_CONTROL_BLOCK

+0x058 CachedSecurity : Ptr64 _CM_KEY_SECURITY_CACHE

+0x060 ValueList : _CHILD_LIST

+0x068 LinkTarget : Ptr64 _CM_KEY_CONTROL_BLOCK

+0x070 IndexHint : Ptr64 _CM_INDEX_HINT_BLOCK

+0x070 HashKey : Uint4B

+0x070 SubKeyCount : Uint4B

+0x078 KeyBodyListHead : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x078 ClonedListEntry : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x088 KeyBodyArray : [4] Ptr64 _CM_KEY_BODY

+0x0a8 KcbLastWriteTime : _LARGE_INTEGER

+0x0b0 KcbMaxNameLen : Uint2B

+0x0b2 KcbMaxValueNameLen : Uint2B

+0x0b4 KcbMaxValueDataLen : Uint4B

+0x0b8 KcbUserFlags : Pos 0, 4 Bits

+0x0b8 KcbVirtControlFlags : Pos 4, 4 Bits

+0x0b8 KcbDebug : Pos 8, 8 Bits

+0x0b8 Flags : Pos 16, 16 Bits

+0x0bc Spare3 : Uint4B

+0x0c0 LayerInfo : Ptr64 _CM_KCB_LAYER_INFO

+0x0c8 RealKeyName : Ptr64 Char

+0x0d0 KCBUoWListHead : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x0e0 DelayQueueEntry : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x0e0 Stolen : Ptr64 UChar

+0x0f0 TransKCBOwner : Ptr64 _CM_TRANS

+0x0f8 KCBLock : _CM_INTENT_LOCK

+0x108 KeyLock : _CM_INTENT_LOCK

+0x118 TransValueCache : _CHILD_LIST

+0x120 TransValueListOwner : Ptr64 _CM_TRANS

+0x128 FullKCBName : Ptr64 _UNICODE_STRING

+0x128 FullKCBNameStale : Pos 0, 1 Bit

+0x128 Reserved : Pos 1, 63 Bits

+0x130 SequenceNumber : Uint8B

I will not document each member individually, but will instead cover them in larger groups according to their common themes and functions.

Reference count

Key Control Blocks are among the most frequently referenced registry objects, as almost every persistent registry operation involves an associated KCB. These blocks are referenced in various ways: by a subkey's KCB.ParentKcb pointer, a symbolic link key's KCB.LinkTarget pointer, through the global KCB tree, via open key handles (and the corresponding key bodies), in pending transacted operations (e.g., the _CM_KCB_UOW.KeyControlBlock pointer), and so on.

For system stability and security, it's crucial to accurately track all these active KCB references. This is done using the RefCount field, the first member in the KCB structure (offset 0x0). Historically a 16-bit field, it became a 32-bit integer, and on modern systems, it is a native word size—typically 64-bits on most computers. Whenever kernel code needs to operate on a KCB or store a pointer to it, it should increment the RefCount using functions from the CmpReferenceKeyControlBlock family. Conversely, when a KCB reference is no longer needed, functions like CmpDereferenceKeyControlBlock should decrement the count. When RefCount reaches zero, the kernel knows the structure is no longer in use and can safely free it.

Besides standard reference counting, KCBs employ optimizations to delay certain memory management processes. This avoids excessive KCB allocation and deallocation when a KCB is briefly unreferenced. Two mechanisms are used: delay deref and delay close. The former delays the actual refcount decrement, while the latter postpones object deallocation even after RefCount reaches zero. Callers must use the specialized function CmpDelayDerefKeyControlBlock for the delayed dereference.

From a low-level security perspective, it's worth considering potential issues related to the reference counting. Integer overflow might seem like a possibility, but it's practically impossible due to the field's width and additional overflow protection present in the CmpReferenceKeyControlBlock-like functions. A more realistic concern is a scenario where the kernel accidentally decrements the refcount by a larger value than the number of released references. This could lead to premature KCB deallocation and a use-after-free condition. Therefore, accurate KCB reference counting is a crucial area to investigate when researching Windows for registry vulnerabilities.

Basic key information

As mentioned earlier, one of the most important types of information in the KCB is the unique identifier of the key in the hive, consisting of the _HHIVE descriptor pointer (KeyHive) and the corresponding key cell index (KeyCell). Very frequently, the kernel uses these two members to obtain the address of the key node mapping, which resembles the following pattern in the decompiled code:

_HHIVE *Hive = Kcb->KeyHive;

_CM_KEY_NODE *KeyNode = Hive->GetCellRoutine(Hive, Kcb->KeyCell);

//

// Further operations on KeyNode...

//

Cached data from the key node

Whenever some information about a key needs to be queried based on its handle, it is generally more efficient to read it from the KCB than the key node. The reason is that a pool-based KCB access requires fewer memory fetches (it avoids the cell map walk), bypasses the context switch to the Registry process, and eliminates the potential need to page in hive data from disk. Consequently, the following types of information are cached inside KCBs:

- Key name, which is stored in a public _CM_NAME_CONTROL_BLOCK structure and pointed to by the NameBlock member. Every unique key name in the system has its own instance of the _CM_NAME_CONTROL_BLOCK object, which is reference-counted and shared across all KCBs of keys with that name. This is an optimization designed to prevent storing multiple redundant copies of the same string in kernel memory.

- Flags, stored in the Flags member and being an exact copy of the _CM_KEY_NODE.Flags value. There is also the KcbUserFlags field that caches the value of _CM_KEY_NODE.UserFlags, and KcbVirtControlFlags, which caches the value of _CM_KEY_NODE.VirtControlFlags. The semantics of all of these bitmasks were discussed in Part 5.

- Security descriptor, stored in a separate _CM_KEY_SECURITY_CACHE structure and pointed to by CachedSecurity.

- Subkey count, stored in the SubKeyCount field. It expresses the cumulative number of the key's stable and volatile subkeys, i.e. it is equal to the sum of _CM_KEY_NODE.SubKeyCounts[0] and SubKeyCounts[1].

- Value list, stored in the ValueList structure of type _CHILD_LIST, and equivalent to _CM_KEY_NODE.ValueList.

- Key limits, represented by KcbMaxNameLen, KcbMaxValueNameLen and KcbMaxValueDataLen. They correspond to the key node fields with the same names without the "Kcb" prefix.

- Fully qualified path, stored in FullKCBName. It is lazily initialized in the internal CmpConstructAndCacheName function, either when resolving a symbolic link, or as a result of calling the documented CmCallbackGetKeyObjectID API. A previously initialized path may be marked as stale by setting FullKCBNameStale (the least significant bit of the FullKCBName pointer).

It is essential for system security that the information found in KCBs is always synchronized with their key node counterparts. This is one of the most fundamental assumptions of the Windows registry implementation, and failure to guarantee it typically results in memory corruption or other severe security vulnerabilities.

Extended flags

In addition to the flags fields that simply mirror the corresponding values from the key node, like Flags, KcbUserFlags and KcbVirtControlFlags, there is also a set of extended flags that are KCB-specific. They are stored in the following fields:

+0x008 ExtFlags : Pos 0, 16 Bits

+0x008 Freed : Pos 16, 1 Bit

+0x008 Discarded : Pos 17, 1 Bit

+0x008 HiveUnloaded : Pos 18, 1 Bit

+0x008 Decommissioned : Pos 19, 1 Bit

+0x008 SpareExtFlag : Pos 20, 1 Bit

[...]

+0x040 DelayedDeref : Pos 0, 1 Bit

+0x040 DelayedClose : Pos 1, 1 Bit

+0x040 Parking : Pos 2, 1 Bit

For the eight explicitly defined flags, here's a brief explanation:

- Freed: the KCB has been freed, but the underlying pool allocation may still be alive as part of the CmpFreeKCBListHead (older systems) or CmpKcbLookaside (Windows 10 and 11) lookaside lists.

- Discarded: the KCB has been unlinked from the global KCB tree and is not available for name-based lookups, but there may still be active references to it via open handles. It is typically set for keys that have been deleted, and for old instances of keys that have been renamed.

- HiveUnloaded: the underlying hive has been unloaded.

- Decommissioned: the KCB is no longer used (its reference count dropped to zero) and it is ready to be freed, but it hasn't been freed just yet.

- SpareExtFlag: as the name suggests, this is a spare bit that may be associated with a new flag in the future.

- DelayedDeref: the key is subject to a "delayed deref" mechanism, due to having been dereferenced using CmpDelayDerefKeyControlBlock instead of CmpDereferenceKeyControlBlock. This serves to defer the actual dereferencing of the KCB by some time, anticipating its near-future need and thus avoiding a redundant free-allocate sequence.

- DelayedClose: the key is subject to a "delayed close" mechanism, which is similar to delayed deref, but it involves delaying the freeing of a KCB structure even if its refcount has dropped to zero.

- Parking: the purpose of this bit is unclear, and it seems to be currently unused.

Last but not least, the ExtFlags member stores a further set of flags, which can be expressed as the following enum:

enum _CM_KCB_EXT_FLAGS

{

CM_KCB_NO_SUBKEY = 0x1,

CM_KCB_SUBKEY_ONE = 0x2,

CM_KCB_SUBKEY_HINT = 0x4,

CM_KCB_SYM_LINK_FOUND = 0x8,

CM_KCB_KEY_NON_EXIST = 0x10,

CM_KCB_NO_DELAY_CLOSE = 0x20,

CM_KCB_INVALID_CACHED_INFO = 0x40,

CM_KCB_READ_ONLY_KEY = 0x80,

CM_KCB_READ_ONLY_SUBKEY = 0x100,

};

Let's break it down:

- CM_KCB_NO_SUBKEY, CM_KCB_SUBKEY_ONE, CM_KCB_SUBKEY_HINT: these flags are currently obsolete, and were originally related to an old performance optimization. CM_KCB_NO_SUBKEY indicated that the key had no subkeys. CM_KCB_SUBKEY_ONE indicated that the key had exactly one subkey, and its 32-bit hint value was stored in KCB.HashKey. Finally, CM_KCB_SUBKEY_HINT indicated that the hints of all subkeys were stored in a dynamically allocated buffer pointed to by KCB.IndexHint. According to my analysis, none of the flags seem to be used in modern versions of Windows, even though their related fields in the KCB structure still exist.

- CM_KCB_SYM_LINK_FOUND: indicates that the key is a symbolic link whose target KCB has already been resolved during a previous access, and is cached in KCB.CachedChildList.RealKcb (older systems) or KCB.LinkTarget (Windows 10 and 11). It is an optimization designed to speed up the process of traversing symlinks, by performing the path lookup only once and later referring directly to the cached KCB where possible.

- CM_KCB_KEY_NON_EXIST: this is another deprecated flag that existed in historical implementations of the registry, but doesn't seem to be used anymore.

- CM_KCB_NO_DELAY_CLOSE: indicates that the key mustn't be subject to the "delayed close" mechanism, and instead should be freed as soon as all references to it are dropped.

- CM_KCB_INVALID_CACHED_INFO: this flag simply indicates that the IndexHint/HashKey/SubKeyCount fields contain out-of-date information that shouldn't be relied on.

- CM_KCB_READ_ONLY_KEY: this key is designated as read-only and, therefore, is not modifiable. The flag can be set by using the undocumented NtLockRegistryKey system call, which can only be called from kernel-mode. Shout out to James Forshaw who wrote an interesting post about it on his blog.

- CM_KCB_READ_ONLY_SUBKEY: the exact meaning and usage of the flag is unclear, but it appears to be enabled for keys with at least one descendant subkey marked as read-only. Specifically, the internal CmLockKeyForWrite function (the main routine behind NtLockRegistryKey's logic) sets it iteratively for every parent key of the read-only key, up to and including the hive's root.

Key body list

To optimize access, the KCB stores the first four key body handles in the KeyBodyArray for fast, lockless access. The KeyBodyListHead field maintains the head of a doubly-linked list for any additional handles.

KCB lock

The KcbPushlock member within the KCB structure is a lock used to synchronize access to the key during various registry system calls. This lock is passed to standard kernel pushlock APIs, such as ExAcquirePushLockSharedEx, ExAcquirePushLockExclusiveEx, and ExReleasePushLockEx

Transacted state

The key control block is central to managing the transacted state of registry keys, maintaining pending changes in memory before they are committed to the hive. Several fields within the KCB are specifically dedicated to this function:

- KCBUoWListHead: This field is a list head that anchors a list of Unit of Work (UoW) structures. Each UoW represents a specific action taken within a transaction, such as creating, deleting a key or setting or deleting a value. This list allows the system to track all pending transactional operations related to a particular key, and it is crucial for ensuring atomicity, as it records the operations that must be applied or rolled back as a single unit.

- TransKCBOwner: This field is used to identify the transaction object that "owns" the key. It is set on the KCBs of transactionally created keys, and signifies that the key is currently only visible in the context of the specific transaction. Once the transaction commits, this field is cleared, and the key becomes visible in the global registry tree.

- KCBLock and KeyLock: Two so-called intent locks of type _CM_INTENT_LOCK, which are used to ensure that no two transactions can be associated with a single key if their respective operations could invalidate each other's state. According to my understanding, KCBLock protects the consistency of the KCB in this regard, and KeyLock protects the key node. The !reg ixlock WinDbg command is designed to display the internal state of these locks.

- TransValueCache: This field is a structure that caches value entries associated with a particular KCB, if at least one of its values has been modified in an active transaction. Before a value is set, modified or deleted within a transaction for the first time, a copy of the current value list is taken and stored here. When a transaction is committed, the TransValueCache state is applied back to the key's persistent value list. On rollback, the list is simply discarded.

- TransValueListOwner: This field is a pointer to a transaction that currently "owns" the TransValueCache. At any given time, for each key, there may be at most one active transaction that has any pending operations involving the key's values.

These fields collectively form the core transaction management within the Windows Registry. Ever since their introduction in Windows Vista, they need to be correctly handled as part of every registry action, be it a read/write one, a transacted/non-transacted one etc. This is because the kernel must potentially incorporate any transacted state in any information queries, and must similarly pay attention not to allow the existence of two contradictory transactions at the same time, and not to allow a non-transacted operation to break any assumptions of an active transaction without invalidating it first. And any bugs related to managing the transacted state may have significant security implications, with some interesting examples being CVE-2023-21748 and CVE-2023-23420. The specific structures used to store the transacted state, such as _CM_TRANS or _CM_KCB_UOW, are discussed in more detail in the "Transaction structures" section below.

Layered key state

Layered keys were introduced in Windows 10 version 1607 to support containerisation through differencing hives. Because overlaying hives on top of each other is primarily a runtime concept, the Key Control Block (KCB) is the natural place to hold the state related to this feature, and there are three main members involved in this process:

- LayerSemantics: This 2-bit field indicates the state of a key within the layering system. It is an exact copy of the key's _CM_KEY_NODE.LayerSemantics value, cached in KCB for easier/quicker access. For a detailed overview of its possible values, please refer to Part 5.

- LayerHeight: This field specifies the level of the key within the differencing hive stack. A higher LayerHeight indicates that the key is higher up in the stack of layered hives, and a value of zero is used for base hives (i.e. normal non-differencing hives loaded on the host system).

- LayerInfo: This is a pointer to a _CM_KCB_LAYER_INFO structure, which describes the key's position within the stack of differencing hives. Among other things, it contains a pointer to the lower layer on the key stack, and the head of a list of layers above the current one.

The specifics of the structures associated with this functionality are discussed in the "Layered keys" section below.