2024-7-18 21:0:0 Author: securityboulevard.com(查看原文) 阅读量:4 收藏

Additional Contributor: Jake Plant, Strategic Delivery Manager

Introduction

In contemporary cybercrime operations, Business Email Compromise (BEC) remains one of the most common threats to organizations across all industries. While BECs do not always require a high degree of technical sophistication from attackers, successful exploitation can be quite lucrative at the expense of their victims. In 2023 alone, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) documented losses of $2.9 billion USD from Business Email Compromise attacks. As high as that figure is, it only includes reported attacks, which limits the ability to fully understand the true financial impacts of BECs.

In early 2024, the GuidePoint Security Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) team investigated one such BEC incident. This investigation revealed several unexpected twists and invaluable lessons for our team. What we uncovered was a stark reminder of the importance of holistically and comprehensively analyzing data to ensure that artifacts that might otherwise be overlooked are not missed, and of the pressing need for heightened cyber and operational security measures in light of the risks present in today’s digital age.

Motive and Methodology

BECs are orchestrated by cybercriminals with the primary intent of financial gain. The threat actors conducting these attacks generally seek to either fraudulently obtain payments from individuals and businesses, or to steal sensitive data such as financial information, intellectual property, or personally identifiable information (PII), which can be sold to third parties or used to extort payment from the victim organization. Typically, BECs are carried out through a combination of methods, including:

- Compromising Legitimate Accounts: Gaining unauthorized access to email accounts through phishing (often using toolkits which can bypass most forms of MFA, such as evilginx), credential theft, or malware infections, enabling attackers to intercept communications and conduct fraudulent activity.

- Social Engineering: Employing manipulative tactics to deceive recipients into taking specific actions, including disclosing sensitive information, or transferring funds.

- Email Spoofing: Impersonating legitimate email addresses to masquerade as trusted individuals, such as clients, employees, vendors, and partners.

- Invoice Fraud: Creating or manipulating invoices, often redirecting legitimate payments to fraudulent accounts controlled by the perpetrators.

(Dis)honor Among Thieves

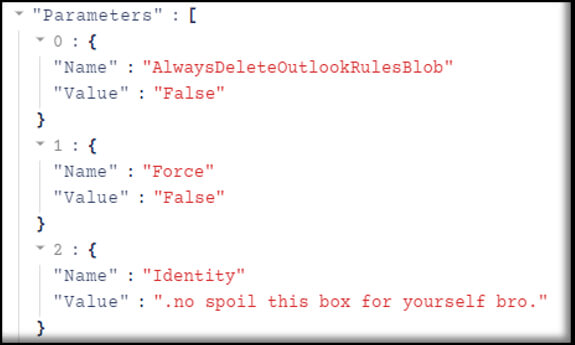

In most BEC cases, an attacker will utilize evasive techniques to prevent the unsuspecting victim from discovering their presence in the victim’s environment. A common method to achieve this is through the creation of email rules in compromised mailboxes that will mark as read, delete, archive, or move emails that meet specific criteria. Because of the frequency with which these steps are taken, artifacts reflecting the creation or modification of email rules are commonly the first investigative focus for analysts upon the commencement of a BEC investigation. While the email rules, in this case, had been deleted by the attacker, certain remnants of the data were still available. Within the traces of this data, the DFIR team noticed several peculiar parameter values being defined.

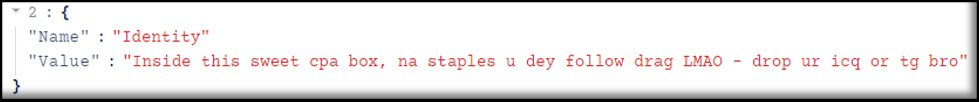

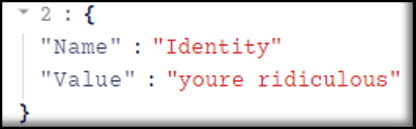

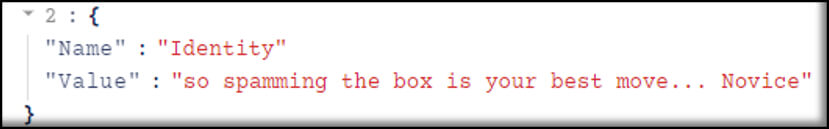

After placing the mail rule events in sequential order and further inspecting other rules and their associated IP addresses (belonging to anonymizing VPN providers), it became evident that two distinct attackers had accessed the victim environment and were corresponding with one another via changes to the compromised mailbox rule parameter values. This two-way banter indicated conflicting motives, light competition, and a few requests to connect directly via chat applications, as outlined below.

In this example, one attacker politely suggested to the other that they avoid losing access to the compromised account or “box”. This is likely a suggestion to show some restraint rather than aggressively making excessive or noticeable changes that could lead to discovery.

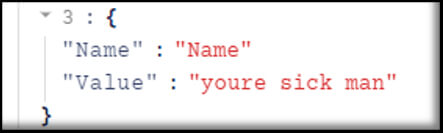

In the next example, we see the that second attacker engaged in some ribbing of the former.

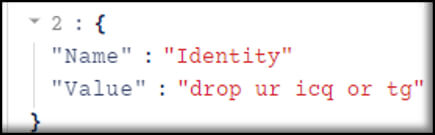

The first attacker would go on to overwrite the mail rule yet again, this time with the hopes of connecting with the second attacker through the anonymous chat services ICQ or Telegram – a communications method likely to be far more convenient than manual mailbox rule modifications.

It doesn’t seem that the second attacker accepted this offer, as the banter continued and escalated to an exchange of insults.

Unfortunately, the scammers’ budding friendship never managed to develop into a deeper connection, as GuidePoint’s triage had begun shortly after the final rule modification. At this point, the “box” had been spoiled for both unauthorized parties, though one of them had elevated their malicious access beyond just email compromise, as we’ll explore in the remainder of this blog post.

Thwarted Payouts

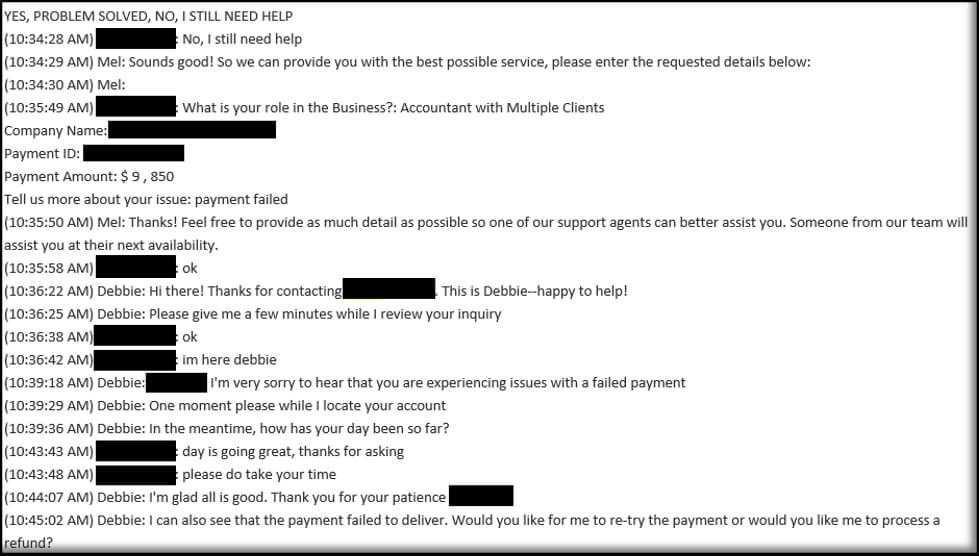

While lurking within the victim’s email account, one of the attackers orchestrated a plan to unlawfully obtain funds using an online bill payment platform that we will refer to as “BillPay.” The attacker created a fictitious health services company that we will call “MedHealth” and registered it with BillPay using an email address specifically created for this attack through the email service, Titan. The attacker issued a charge of nearly $10,000 to the victim’s existing BillPay account from the fake MedHealth company, hoping to approve the transactions using the victim’s email for authorization.

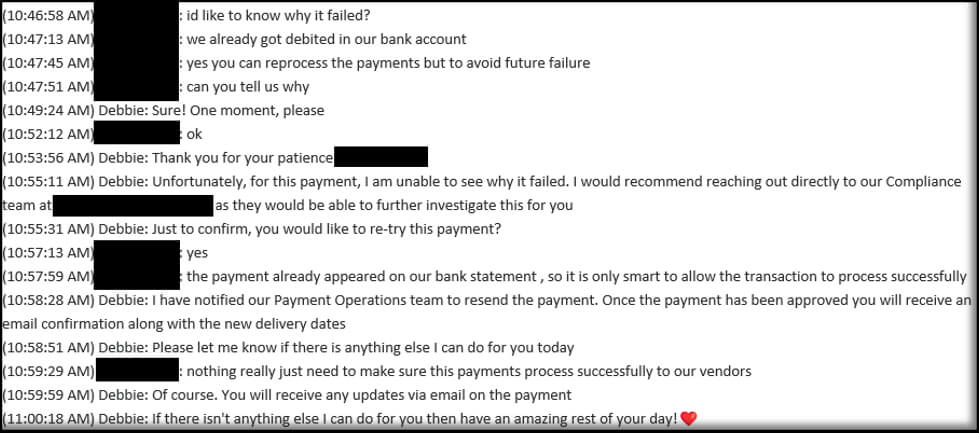

Fortunately, the legitimate BillPay platform declined the suspicious transactions, requiring additional information before they would provide approval. Not to be deterred, the attacker went on to impersonate the compromised user in a support chat with BillPay, the full transcript of which was then sent to the RSS subscriptions folder of the compromised user’s mailbox. The RSS subscriptions folder is commonly used by BEC attackers to avoid detection, as it is often overlooked and not monitored closely. To the benefit of the investigation, the attacker failed to delete this transcript, providing GuidePoint with access to the entire conversation.

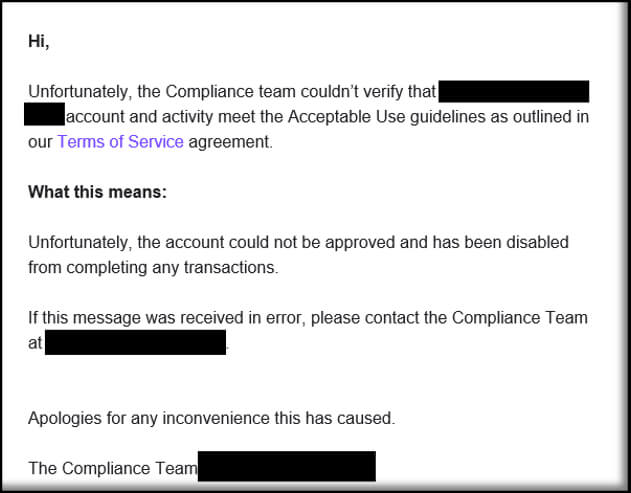

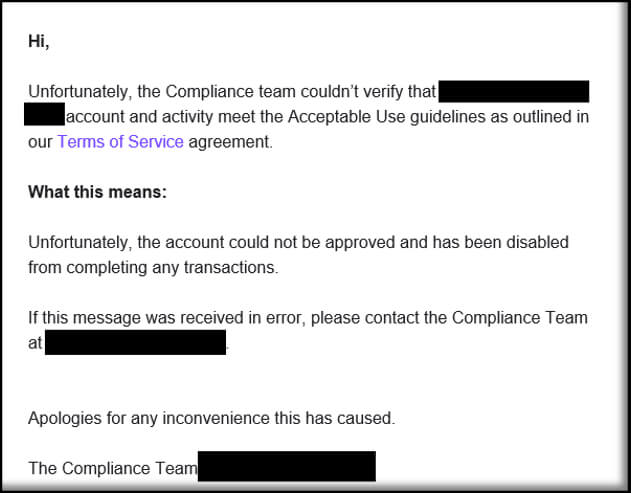

BillPay’s Compliance Team later followed up with the attacker, noting that the fake company MedHealth did not meet their terms of use.

As time went on, this attacker ventured into yet another bill payment system, targeting a service integral to the victim organization’s daily operations. Employing another guise, the attacker used a spoofed domain to masquerade as a bona fide customer, likely based on intercepted legitimate email conversations concerning ACH payments. The attacker created entirely new email threads mirroring the legitimate ones but replaced original recipients with similarly-named, phony recipients under the spoofed domain. In this instance, the stakes were higher, with multiple transactions exceeding $100,000 USD in total. Fortunately, GuidePoint’s scrutiny of the victim’s mailbox enabled interception of the attacker, affording the organization an opportunity to promptly halt the transactions and foil the attacker’s plans.

Browser Syncing is Convenient (for DFIR)

To ensure a thorough investigation, GuidePoint DFIR prefers to analyze the primary workstation(s) of a BEC victim. We begin by searching for traces of malware, such as infostealers, or any other compromise that might have facilitated the initial theft of account credentials. Our process allows us to perform meticulous threat hunting and analysis, ranging from scrutinizing Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) data (when available), as well as native Operating System (OS) artifacts that might not be available within EDR telemetry or log retention.

As our analysis of the user’s machine did not unearth any signs of a malware infection or other compromise, our focus initially remained on Microsoft 365 and the payment systems abused by the attacker. However, despite this lack of evidence, we noted some anomalies in the user’s browser history. We observed some inexplicable visits to websites like Kraken, a cryptocurrency exchange, and Titan Email, which was previously leveraged by the attacker during the BEC. It was not initially clear why there would be indications of access to these resources — which the user had no memory of accessing — if the attacker did not have access to the victim’s system.

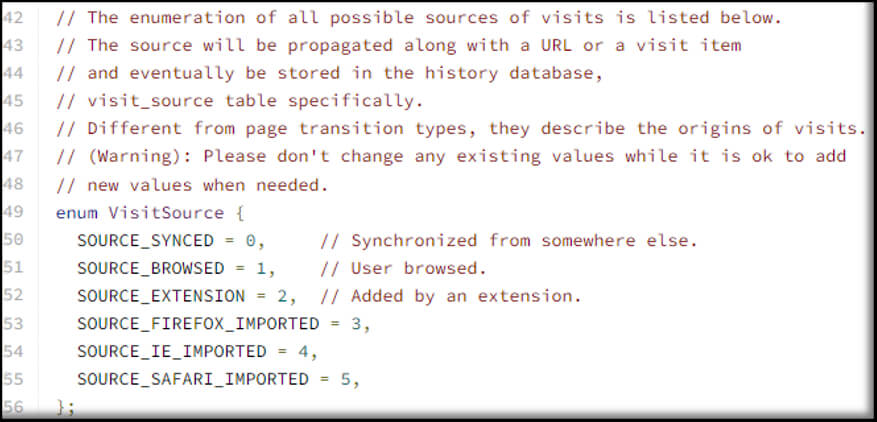

To further unravel this mystery, we had to delve into the mechanics of Chromium browser history syncing. This feature, which must be enabled for a user account — and was in this instance — synchronizes browsing history to the local history file rather than relying on a cloud-based linkage. This means that if an attacker logs into a Chromium-based browser with a compromised account, it would be possible to enumerate the attacker’s web history by analyzing the victim’s machine, even if the machine itself was untouched during the attack. Consequently, this enabled GuidePoint to enumerate a trove of attacker web browsing activity, distinguishing between synced and local history events. As we commenced analysis of the history database, a clearer picture of the attacker’s activity emerged. A field within the visit_source table in the history database indicates the origin of each historical event, including whether it was synced from a separate device. The definitions for each value located in this field are available within the Chromium source code. Fortunately, the legitimate user did not use their account on any other machine, so we could be sure that anything synced would have been the attacker’s activity.

With the history database in hand and some very simple SQL queries, we were able to perform some joins to enumerate visits in the user’s browser history that originated from an outside device. This can be executed in multiple ways, such as within DB Browser for SQLite:

SELECT urls.*

FROM urls

JOIN visits ON urls.id = visits.url

JOIN visit_source ON visits.id = visit_source.id

WHERE visit_source.source = '0'

ORDER BY urls.last_visit_time ASC;The exported results provided a clear timeline of the attacker logging into the victim’s account before browsing various resources, likely in an attempt to use synced credentials to access payment-related resources in addition to the compromised user’s mailbox. The browsing behavior included the anomalous access to Kraken and Titan Email. This brings us to another relevant point for both analysts and end users, as Chromium browsers not only synchronize browsing history, but also saved passwords…

What’s “OPSEC?”

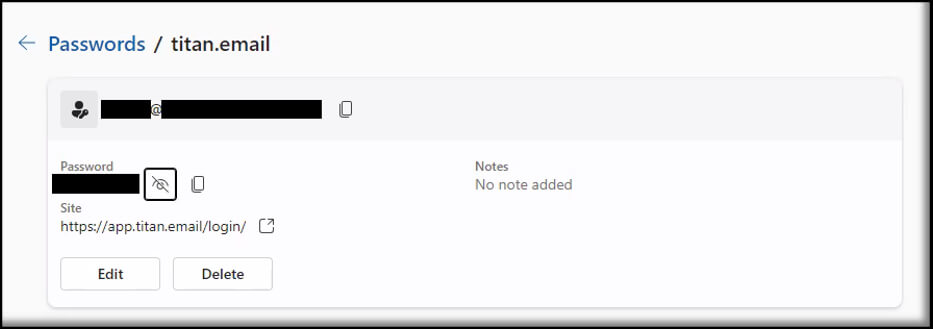

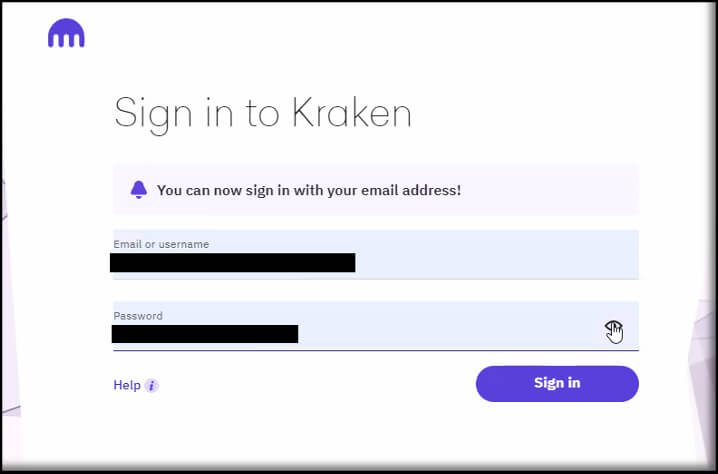

Further exploration of the user’s browser data revealed intriguing entries beyond just browsing history. There were also saved credentials that piqued our interest–notably, for both Kraken and Titan Email.

In Chromium browsers, the “Login Data” database stores passwords saved to the browser that are encrypted by DPAPI, which means the credentials are only decryptable during the system owner’s active Windows sessions. For attackers, this presents a hurdle; to pilfer these credentials with tools like infostealers, it must be executed under the user’s context while they are logged in to the machine. For GuidePoint, however, it was as simple as a screensharing session with the user and inspecting their saved browser passwords. If autofill is also enabled, it is possible to view them on the respective website’s login page.

As seen below, the username for Titan Email was linked to the same email address registered in “BillPay” for the sham company concocted by the attacker, indicating that this was almost certainly an attacker-controlled account.

Similarly, the username for Kraken was the same spoofed email address used by the attacker to impersonate a legitimate customer. Again, this reuse of attacker infrastructure gave us a high level of confidence that this was an attacker-controlled account, and not a resource of the compromised user.

GuidePoint (with the cooperation of the victim) promptly provided law enforcement with credentials to both the Titan Email and Kraken accounts, which had presumably been used to facilitate financial theft from this victim and potentially others. If any funds remain in the attacker’s Kraken Wallet, the authorities now have access to them as well as any other details that may be available in the account.

Wrap-up

At least one of the attackers in this incident experienced a plethora of major setbacks, with their access to the compromised account revoked, and seemingly imminent fraudulent payments halted before they could come to fruition. When attempting to exploit browser credential syncing, the attacker inadvertently dropped an “Uno Reverse” card on themselves, giving up access credentials for their own services in an OPSEC mistake that certainly wouldn’t have make their already challenging day any easier.

Investigating M365 BEC cases frequently entails scrutinizing an array of logs accessible within the Microsoft ecosystem. These investigations have become somewhat routine within the Digital Forensics & Incident Response community, given the prevalence of these attacks and their recurring patterns. However, effective defense against BEC requires more than just understanding these patterns. The following best practices are essential for investigators, defenders, and organizations alike to mitigate and prevent these threats:

- Enforcing strong password hygiene and fortifying authentication practices are crucial in safeguarding against cyber threats. While modern attackers employ methods to bypass many Multifactor Authentication (MFA) controls for BEC, a combination of MFA and Conditional Access Policies can mitigate an attacker’s ability to gain access to the victim environment, even with valid credentials.

- Defenders’ use of all available resources, and creative, vigilant review of available datasets can provide invaluable insights for investigating, mitigating, and defending against BEC attacks. In the case of this investigation, our findings would not have been possible without having examined the user’s workstation and actively sought out a deeper understanding of Chromium browsers and the artifacts they generate.

- Dutiful monitoring of any and all financial transaction systems is imperative to further deter the success of fraudulent payments. In a massive win, the victim was able to prevent the transfer of over $100,000. However, future victims may not be so fortunate or could face a more determined and sophisticated adversary.

- Employee awareness and training can be pivotal to entirely preventing BEC attacks and stopping them after the initial compromise has occurred. While phishing awareness and security training are now common in the workplace, awareness of BEC and its warning signs is less common and reporting is often less prompt.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from The Guiding Point | GuidePoint Security authored by Gabe Renfro. Read the original post at: https://www.guidepointsecurity.com/blog/fraudsters-fumble-from-phish-to-failure/

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh