PHISHING SCHOOL

Bypassing Web Proxies so Your Phish Don’t Suffocate

You just fought long and hard to convince a user to click on your link. They are dying to know about the contents of your macro enabled excel file. So, don’t let web proxies ruin your fun by blocking your payload! We are in the home stretch, but that doesn’t mean we get to take a victory lap just yet.

The Good Ol’ Days

I remember it well. The year was 2014, and I was embarking on my first phishing expedition as a fledgling penetration tester. I fired up my Metasploit listener, minted an EXE payload with Veil, and called it ‘dresscode_policy.doc.exe’. I sent out my emails and, in return, was blessed with a bounty of shells raining in from the deep blue internet. In those days, it seemed like there would always be phish on the table. Looking back now, I can hardly believe it was ever so easy.

Sparse Waters

We’ve continued to overphish the same waters year after year with reckless abandon and now the phish don’t bite like they used to. The same bait doesn’t work. The same nets come up empty. We have only ourselves to blame for being so selfish (selphish?). We used EXEs like harpoons and now they are completely blocked unless they are signed. We wove nets of PowerShell until AMSI and constrained language mode cut them to ribbons. We dredged scores of users with Excel macros until Microsoft almost did away with macros entirely. We even used mark of the web bypasses to the brink of extinction.

How will we ever catch a phish again?

What’s Really Happening

I was being a bit dramatic, but I did want to make one point:

Defenses adapt to threats and we are the threats.

As new phishing techniques emerge, one of the most obvious defenses has always been to try to block initial access payloads based on their file type. Someone starts slinging malware in Microsoft Excel add-in (XLL) files, and suddenly it makes sense for most organizations to just block these files outright. Payload types that were ‘working’ across the board just months ago tend to make too much noise and now get blocked.

We may mourn the fall of our favorite initial access payloads (R.I.P. OLE), but not all hope is lost. Let’s talk about the challenge of initial access from a high level so we can see our options more clearly. First, we’ll talk about objectives, then discuss defenses, and finally bypasses!

Can It Run Code?

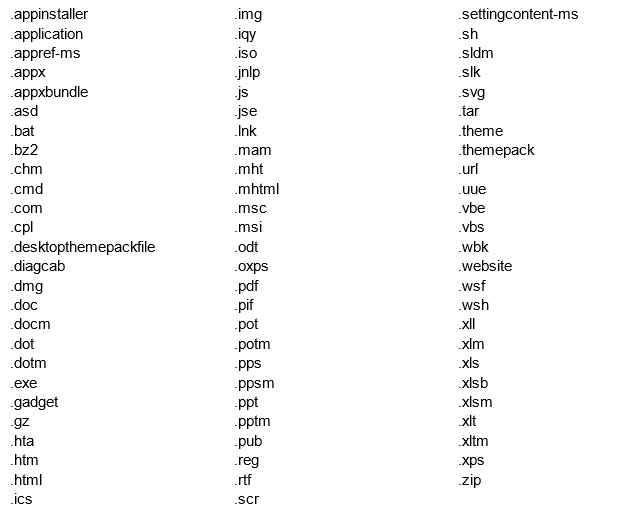

If a file type can run code, or open another application that can run code, then it can likely be used for initial access. To get a full list of potentially dangerous files, we can look at the ones blocked by default on Outlook:

The list is 120 entries long! And even that is not the full list, considering that Outlook still allows dangerous file types like macro enabled Office documents. Thanks to @mrd0x, another good source is filesec.io:

Use the “Double Click” filter to find file types that are particularly useful for phishing. These “Double Click” files initiate some action when clicked by a user. Often running a script or executable of some kind. That list is 77 entries long!

Our goal for initial access is to successfully deliver at least one of these files to the target and convince them to open/run it. Which file types are allowed will vary depending on controls in your target environment, but it is extremely unlikely that all of these file types are blocked. Often, several of these “dangerous” files are used in business processes and have exceptions applied to them. We just need to find one exception!

The Wall

There is a wall between us and our target. It is lined with turrets that want to destroy our payload. This wall consists of the corporate proxy, the corporate firewall, and the target’s browser. Each has some visibility into what users are downloading and each will try to prevent users from inviting us into the network, but there’s a problem with their eyesight. They really only have three ways of knowing what file type is being downloaded, and we can control each one.

- Extensions — The last characters of the file name (e.g., doc, txt, exe)

- MIME Types — The content type we specify in our server response headers (e.g., application/msword, text/plain, application/x-msdownload)

- Magic Numbers — The first bytes in a file (e.g., “50 4B 03 04” for .zip files or “4D 5A” for Windows executables)

Under normal circumstances, these indicators should all tell a consistent story like:

A windows executable with an extension of “exe”, AND a MIME type of “application/x-msdownload”, AND “4D 5A” (the “MZ” header) as the first two bytes.

Therefore, you could write a program to detect these dangerous files based on any single characteristic. Writing detections based on all three would be extremely redundant. I suspect many software engineers have made this very mistake. Choosing a single indicator, writing the detection logic, and thinking that would be enough. However, it’s the contents of the file and not its name, MIME type, or magic number that make it dangerous. Now that we have a clear view of our adversary, let’s talk about how we might slip past their watch.

Bypasses

As I mentioned, we will need to slip past the proxy, firewall, and browser controls to get our payload on the target’s system; however, for sake of example, let’s say the most restrictive of these controls is the corporate proxy. System administrators have fine tuned their proxy rules to block any attempts to download known malicious file types over HTTP and HTTPS. Similar rules apply to the other two, but it will help to focus on just one control for now.

Bypass 1 — Exceptions

I told you that the proxy was going to block all malicious files, but were you really going to just take my word for it without testing? Tisk tisk! As mentioned earlier, there are tons of potentially malicious file types we can use. Some may be too obscure for network defenders to even know about. Others might need to be explicitly allowed because of a business need. Wouldn’t it cause problems for many companies if every Office document hosted on OneDrive was suddenly blocked? How long will our system administrators take the heat before they cave in and put in an exception? In practice, I have found these surprisingly often, so you might just get lucky.

Bypass 2 — Embed in HTML

Did you know you can dynamically generate a blob of data in JavaScript, in the browser, and then use just JavaScript to “Download” the contents to a file? This is a totally legitimate feature for most browsers. For example, web developers might need a way to expose a button on a page to download the contents of a “table” element to a CSV file for the user.

We can use this same feature to download arbitrary file contents to arbitrary file names. What makes this technique so useful to us is that there is no separate call to the server to download the payload. We can slip the contents of our payload inside a ‘script’ tag in an HTML document like a Trojan horse. The proxy will only see the HTML document being downloaded, and not know it contains another malicious file inside it. This technique is known as “Embed in HTML’’ and there are several tools that can help us automate weaponization. Here’s one that I’ve used for years:

https://github.com/Arno0x/EmbedInHTML

You might want to make a few tweaks so that you aren’t signatured based on the template, but the project is a great example of how to execute this attack well using encryption to further protect your payload.

Bypass 3 — Password Protected ZIP

I have found that ZIP files are very commonly allowed in corporate environments. There are so many legitimate uses for ZIP that it would be prohibitive to block them outright. To account for potentially dangerous ZIP files, many security products will actually unzip the contents to see what’s inside before making a determination about whether it is safe.

But what if they can’t open it? What if we include a password in our phishing email that the target will then use to open a password protected ZIP file? In most cases, the security product will not be able to properly vet the file, but will let the user download it anyway. I’ve used this technique with great success to slip all sorts of sketchy file types past corporate proxies.

Bypass 4 — FTP and WebDAV

Did you know that most browsers support FTP URLs? In our example of an extremely restrictive web proxy blocking downloads of HTTP and HTTPS, sending the user to an FTP share might slip past unnoticed. In addition, depending on how the proxy settings are being applied, they might not be enforced for explorer.exe visiting a WebDAV share. In that case, you might instruct a target to copy a UNC path and paste it into the file explorer.

Bypass 5 — MIME Trickery

Sometimes, we can get the receiving web browser to know the “real” payload type based on its MIME type, and spoof the file extension. A classic example of this is that Internet Explorer treats any file with the MIME type “application/hta” as an HTA file and will prompt the user to execute it. If our example proxy is blocking our “payload.hta” file based on the file extension, we can simply rename the file to “payload.pdf” while still specifying the HTTP header “Content-Type: application/hta” from our server.

Bypass 6 — Change the Extension

Let’s say that you want to deliver a PowerShell script to stage your malware, but the proxy blocked PS1 files. What if we just put the script in a TXT file and ask the target user to change the file name for us? Along the same lines, you might add a nonsense extension to the file and then instruct the user that they will need to select an application to open it (e.g., PowerShell). Sure, it’s not quite as convenient as having them just double-click the file, but you might be surprised what additional requests we can tack onto our phishing message if we already have them on the hook.

Bypass 7 — Magic Number Stomping

I’ve seen many cases where I’ve successfully delivered a stager written in Windows scripting utilities like PowerShell, VBA, JScript, etc. and seen a request from my stager to load the full payload, only to have the stager immediately die. What I found in several of these cases is that because I was staging a .NET assembly or other Windows executable, the download for my full payload was being signatured and blocked based on the first two bytes of the file. In this case, the “MZ” header that prepends all Windows EXE and DLL files. To get around this, a quick fix that has turned out to be really effective is just to remove those first two bytes from the file and then programmatically add them back using some logic in my stager.

Bypass 8 — Poison Existing Documents

Instead of trying to directly deliver payloads with our phishing campaign, what if we use CuddlePhish to first gain access to O365, Gmail, or Okta, and then abuse the target’s access to backdoor files we find on OneDrive, Teams, Google Drive, etc? If you aren’t familiar with CuddlePhish, it’s a tool we can use to bypass multi-factor authentication (MFA) while forcing phishing targets to log into services for us.

The point here is that instead of delivering payloads from our phishing site, we target access to the places where we expect our target organization is storing and sharing documents. You could even take this a step further and use access to Outlook webmail and Teams to message other employees at the target organization and prompt them to “review your changes” to your poisoned documents.

Addressing the Whale in the Boat: A.K.A. Mark of the Web

Many red teamers get discouraged by the mark of the web (MOTW) and treat it like it’s a death sentence for any payload they wish to deliver during phishing. I have to say that this is simply not the case. I think it’s very rarely the MOTW that is the last nail in the coffin for phishing payloads. For one, I know of at least two MOTW bypasses that still work (sorry, but I’m not sharing those at this time), so I know there are bound to be more. If you dig around, then I’m sure you can find one.

Secondly, MOTW doesn’t always mean your payload is belly-up and dead in the water. For many file types, it just adds another annoying prompt or two to make sure the user really wants to “keep” and “open” the sketchy file.

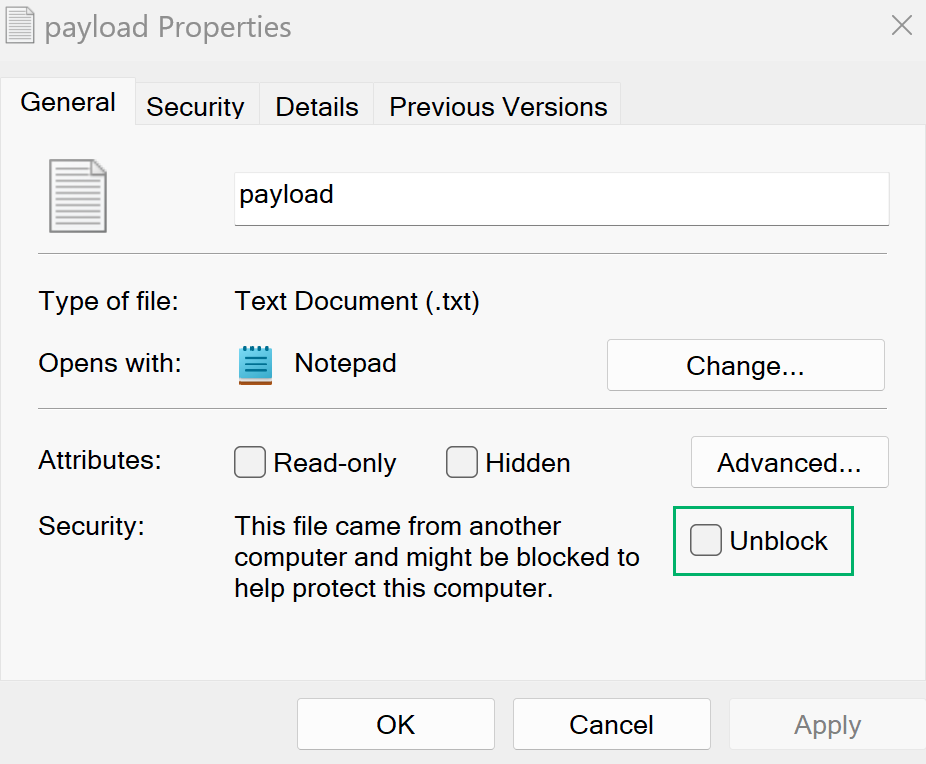

Finally, you can always just ask your target to right-click on the file, select “Properties”, and check the “Unblock” button:

It really is that easy! Keep in mind that this is the absolute most difficult MOTW bypass out there and it’s not that hard. Most users will be willing and able to perform this bypass for you.

In Conclusion

Proxies, firewalls, and browsers are going to try to block sketchy files and that can really take the wind out of our sails when trying to deliver payloads with phishing. Luckily, we have options, somewhere in the range of dozens to hundreds of options, so it’s unlikely that every single potentially malicious file type is blocked. In addition, most security products only block file types based on attributes that we can control. Therefore, we have several tricks we can use to potentially bypass them. Worst case scenario, we just need a little extra social engineering to get our targets to make a file modification before opening/running our payload.

And remember! Phish are friends, not food…

Phish Out of Water was originally published in Posts By SpecterOps Team Members on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Posts By SpecterOps Team Members - Medium authored by Forrest Kasler. Read the original post at: https://posts.specterops.io/phish-out-of-water-aaeb677a5af3?source=rss----f05f8696e3cc---4

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh