PHISHING SCHOOL

Bypassing Phishing Link Filters

You could have a solid pretext that slips right by your target secure email gateway (SEG); however, if your link looks too sketchy (or, you know, “smells phishy”), your phish could go belly-up before it even gets a bite. That’s why I tend to think of link filters as their own separate control. Let’s talk briefly about how these link filters work and then explore some ways we might be able to bypass them.

What the Filter? (WTF)

Over the past few years, I’ve noticed a growing interest in detecting phishing based on the links themselves–or, at least, there are several very popular SEGs that place a very high weight on the presence of a link in an email. I’ve seen so much of this that I have made this type of detection one of my first troubleshooting steps when a SEG blocks me. I’ll simply remove all links from an email and check if the message content gets through.

In at least one case, I encountered a SEG that blocked ANY email that contained a link to ANY unrecognized domain, no matter what the wording or subject line said. In this case, I believe my client was curating a list of allowed domains and instructed the SEG to block everything else. It’s an extreme measure, but I think it is a very valid concern. Emails with links are inherently riskier than emails that do not contain links; therefore, most modern SEGs will increase the SPAM score of any message that contains a link and often will apply additional scrutiny to the links themselves.

How Link Filters Work — Finding the Links

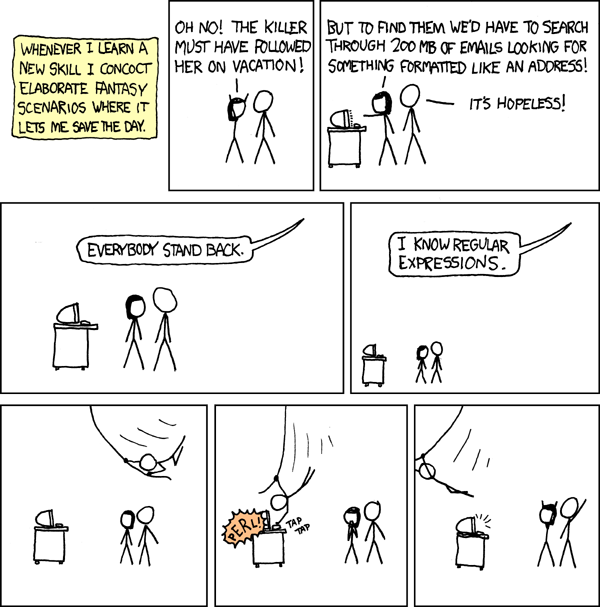

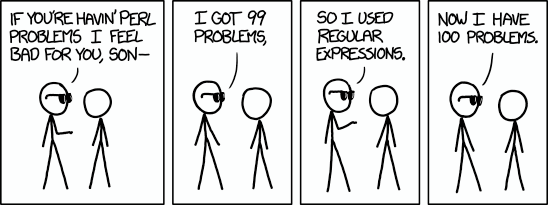

If a SEG filters links in an email, it will first need to detect/parse each link in the content. To do this, almost any experienced software engineer will directly go to using Regular Expressions (“regex” for short):

To which, any other experienced software engineer will be quick to remind us that while regex is extremely powerful, it is also easy to screw up:

As an example, here are just a few of the top regex filters I found for parsing links on stackoverflow:

(http|ftp|https):\/\/([\w_-]+(?:(?:\.[\w_-]+)+))([\w.,@?^=%&:\/~+#-]*[\w@?^=%&\/~+#-])

(?:(?:https?|ftp|file):\/\/|www\.|ftp\.)(?:\([-A-Z0–9+&@#\/%=~_|$?!:,.]*\)|[-A-Z0–9+&@#\/%=~_|$?!:,.])*(?:\([-A-Z0–9+&@#\/%=~_|$?!:,.]*\)|[A-Z0–9+&@#\/%=~_|$])

(?:(?:https?|ftp):\/\/)?[\w/\-?=%.]+\.[\w/\-&?=%.]+

([\w+]+\:\/\/)?([\w\d-]+\.)*[\w-]+[\.\:]\w+([\/\?\=\&\#\.]?[\w-]+)*\/?

(?i)\b((?:[a-z][\w-]+:(?:/{1,3}|[a-z0–9%])|www\d{0,3}[.]|[a-z0–9.\-]+[.][a-z]{2,4}/)(?:[^\s()<>]+|\(([^\s()<>]+|(\([^\s()<>]+\)))*\))+(?:\(([^\s()<>]+|(\([^\s()<>]+\)))*\)|[^\s`!()\[\]{};:’”.,<>?«»“”‘’]))

Don’t worry if you don’t know what any of these mean. I consider myself to be well versed in regex and even I have no opinion on which of these options would be better than the others. However, there are a couple things I would like to note from these examples:

- There is no “right” answer; URLs can be very complex

- Most (but not all) are looking for strings that start with “http” or something similar

These are also some of the most popular (think “smart people”) answers to this problem of parsing links. I could also imagine that some software engineers would take a more naive approach of searching for all anchor (“<a>”) HTML tags or looking for “href=” to indicate the start of a link. No matter which solution the software engineer chooses, there are likely going to be at least some valid URLs that their parser doesn’t catch and might leave room for a categorical bypass. We might also be able to evade parsers if we can avoid the common indicators like “http” or break up our link into multiple sections.

Side Note: Did you see that some of these popular URL parsers account for FTP and some don’t? Did you know that most browsers can connect to FTP shares? Have you ever tried to deliver a phishing payload over an anonymous FTP link?

How Link Filters Work — Filtering the Links

Once a SEG has parsed out all the links in an email, how should it determine which ones look legitimate and which ones don’t? Most SEGs these days look at two major factors for each link:

- The reputation of the domain

- How the link “looks”

Checking the domain reputation is pretty straightforward; you just split the link to see what’s between the first two forward slashes (“//”) and the next forward slash (“/”) and look up the resulting domain or subdomain on Virustotal or similar. Many SEGs will share intelligence on known bad domains with other security products and vice versa. If your domain has been flagged as malicious, the SEG will either block the email or remove the link.

As far as checking how the link “looks”, most SEGs these days use artificial intelligence or machine learning (i.e., AI/ML) to categorize links as malicious or benign. These AI models have been trained on a large volume of known-bad links and can detect themes and patterns commonly used by SPAM authors. As phishers, I think it’s important for us to focus on the “known-bad” part of that statement.

I’ve seen one researcher’s talk who claimed their AI model was able to detect over 98% of malicious links from their training data. At first glance, this seems like a very impressive number; however, we need to keep in mind that in order to have a training set of malicious links in the first place, humans had to detect 100% of the training set as malicious. Therefore, the AI model was only 98% as good as a human at detecting phishing links solely on the “look” of the link. I would imagine that it would do much worse on a set of unknown-bad links, if there was a way to hypothetically attain such a set. To slip through the cracks, we should aim to put our links in that unknown-bad category.

Even though we are up against AI models, I like to remind myself that these models can only be trained on human-curated data and therefore can only theoretically approach the competence of a human, but not surpass humans at this task. If we can make our links look convincing enough for a human, the AI should not give us any trouble.

Bypassing Link Filters

Given what we now know about how link filters work, we should have two main tactics available to us for bypassing the filter:

- Format our link so that it slips through the link parsing phase

- Make our link “look” more legitimate

If the parser doesn’t register our link as a link, then it can’t apply any additional scrutiny to the location. If we can make our link location look like some legitimate link, then even if we can’t bypass the parser, we might get the green light anyway. Please note that these approaches are not mutually exclusive and you might have greater success mixing techniques.

Bypassing the Parser

Don’t use an anchor tag

One of the most basic parser bypasses I have found for some SEGs is to simply leave the link URL in plaintext by removing the hyperlink in Outlook. Normally, link URLs are placed in the “hypertext reference” (href) attribute of an HTML anchor tag (<a>). As I mentioned earlier, one naive but surprisingly common solution for parsing links is to use an HTML parsing library like BeautifulSoup in Python. For example:

soup = BeautifulSoup(email.content, 'html.parser')

links = soup.find_all("a") # Find all elements with the tag <a>

for link in links:

print("Link:", link.get("href"), "Text:", link.string)

Any SEG that uses this approach to parse links won’t see a URL outside of an anchor tag. While a URL that is not a clickable link might look a little odd to the end user, it’s generally worth the tradeoff when this bypass works. In many cases, mail clients will parse and display URLs as hyperlinks even if they are not in an anchor tag; therefore, there is usually little to no downside of using this technique.

Use a Base Tag (a.k.a BaseStriker Attack)

One interesting method of bypassing some link filters is to use a little-known HTML tag called “base”. This tag allows you to set the base domain for any links that use relative references (i.e., links with hrefs that start with “/something” instead of direct references like “https://example.com/something”). In this case, the “https://example.com” would be considered the “base” of the URL. By defining the base using the HTML base tag in the header of the HTML content, you can then use just relative references in the body of the message. While HTML headers frequently contain URLs for things like CSS or XML schemas, the header is usually not expected to contain anything malicious and may be overlooked by a link parser. This technique is known as the “BaseStriker” attack and has been known to work against some very popular SEGs:

The reason why this technique works is because you essentially break your link into two pieces: the domain is in the HTML headers, and the rest of the URL is in your anchor tags in the body. Because the hrefs for the anchor tags don’t start with “https://” they aren’t detected as links.

Scheming Little Bypasses

The first part of a URL, before the colon and forward slashes, is what’s known as the “scheme”:

URI = scheme ":" ["//" authority] path ["?" query] ["#" fragment]

As mentioned earlier, some of the more robust ways to detect URLs is by looking for anything that looks like a scheme (e.g. “http://”, or “https://”), followed by a sequence of characters that would be allowed in a URL. If we simply leave off the scheme, many link parsers will not be able to detect our URL, but it will still look like a URL to a human:

accounts.goooogle.com/login?id=34567

A human might easily be convinced to simply copy and paste this link into their browser for us. In addition, there are quite a few legitimate schemes that could open a program on our target user’s system and potentially slip through a URL parser that is only looking for web links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_URI_schemes

There are at least a few that could be very useful as phishing links 😉

QR Phishing

What if there isn’t a link in the email at all? What if it’s an image instead? You can use a tool like SquarePhish to automate phishing with QR codes instead of traditional links:

GitHub – secureworks/squarephish

I haven’t played with this yet, but have heard good things from friends that have used similar techniques. If you want to play with automating this attack yourself, NodeJS has a simple library for generating QRs:

Bypassing the Filter

Don’t Mask

(Hold on. I need to get on my soapbox…) I can’t count how many times I’ve been blocked because of a masked link only to find that unmasking the link would get the same pretext through. I think this is because spammers have thoroughly abused this feature of anchor tags in the past and average email users seldom use masked links. Link filters tend to see masked links as far more dangerous than regular links; therefore, just use a regular link. It seems like everyone these days knows how to hover a link and check its real location anyway, so masked links are even bad at tricking humans now. Don’t be cliche. Don’t use masked links.

Use Categorized Domains

Many link filters block or remove links to domains that are either uncategorized, categorized as malicious, or were recently registered. Therefore, it’s generally a good idea to use domains that have been parked long enough to be categorized. We’ve already touched on this in “One Phish Two Phish, Red Teams Spew Phish”, so I’ll skip the process of getting a good domain; however, just know that the same rules apply here.

Use “Legitimate” Domains

If you don’t want to go through all the trouble of maintaining categorized domains for phishing links, there are some generally trustworthy domains you can leverage instead. One example I recently saw “in-the-wild” was a spammer using a sites.google.com link. They just hosted their phishing page on Google! I thought this was brilliant because I would expect most link filters to allow Google, and even most end users would think anything on google.com must be legit. Some other similar examples would be hosting your phishing sites as static pages on GitHub, in an S3 bucket, other common content delivery networks (CDNs), or on SharePoint, etc. There are tons of seemingly “legitimate” sites that allow users to host pages of arbitrary HTML content.

Arbitrary Redirects

Along the same lines as hosting your phishing site on a trusted domain is using trusted domains to redirect to your phishing site. One classic example of this would be link shorteners like TinyURL. While TinyURL has been abused for SPAM to the point that I would expect most SEGs to block TinyURL links, it does demonstrate the usefulness of arbitrary redirects.

A more useful form of arbitrary redirect for bypassing link filters are URLs with either cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities that allow us to specify a ‘window.location’ change or URLs that take an HTTP GET parameter specifying where the page should redirect to. As part of my reconnaissance phase, I like to spend at least a few minutes on the main website of my target to look for these types of vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities are surprisingly common and while an arbitrary redirect might be considered a low-risk finding on a web application penetration test report, they can be extremely useful when combined with phishing. Your links will point to a URL on your target organization’s main website. It is extremely unlikely that a link filter or even a human will see the danger. In some cases, you may find that your target organization has configured an explicit allow list in the SEG for links that point to their domains.

Link to an Attachment

Did you know that links in an email can also point to an email attachment? Instead of providing a URL in the href of your anchor tag, you can specify the content identifier (CID) of the attachment (e.g. href=“cid:[email protected]”). One way I have used this trick to bypass link filters is to link to an HTML attachment and use obfuscated JavaScript to redirect the user to the phishing site. Because our href does not look like a URL, most SEGs will think our link is benign. You could also link to a PDF, DOCX, or several other usually allowed file types that then contain the real phishing link. This might require a little more setup in your pretext to instruct the user, or just hope that they will click the link after opening the document. In this case, I think it makes the most sense to add any additional instructions inside the document where the contents are less likely to be scrutinized by the SEG’s content filter.

Pick Up The Phone

This blog rounds out our “message inbound” controls that we have to bypass for social engineering pretexts. It would not be complete without mentioning one of the simplest bypasses of them all:

Not using email!

If you pick up the phone and talk directly to your target, your pretext travels from your mouth, through the phone, then directly into their ear, and hits their brain without ever passing through a content or reputation filter.

Along the same lines, Zoom calls, Teams chats, LinkedIn messaging, and just about any other common business communication channel will likely be subject to far fewer controls than email. I’ve trained quite a few red teamers who prefer phone calls over emails because it greatly simplifies their workflow. Just a few awkward calls is usually all it takes to cede access to a target environment.

More interactive forms of communication, like phone calls, also allow you to gauge how the target is feeling about your pretext in real time. It’s usually obvious within seconds whether someone believes you and wants to help or if they think you’re full of it and it’s time to cut your losses, hang up the phone, and try someone else. You can also use phone calls as a way to prime a target for a follow-up email to add perceived legitimacy. Getting our message to the user is half the battle, and social engineering phone calls can be a powerful shortcut.

In Summary

If you need to bypass a link filter, either:

- Make your link look like it’s not a link

- Make your link look like a “legitimate” link

People still use links in emails all the time. You just need to blend in with the “real” ones and you can trick the filter. If you are really in a pinch, just call your targets instead. It feels more personal, but it gets the job done quickly.

Feeding the Phishes was originally published in Posts By SpecterOps Team Members on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Posts By SpecterOps Team Members - Medium authored by Forrest Kasler. Read the original post at: https://posts.specterops.io/feeding-the-phishes-276c3579bba7?source=rss----f05f8696e3cc---4

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh