In the last part of my Build simple fuzzer series I’ve promised some topics like patched binaries and performance counters. I’ve even implemented those things but decided that it is fairly repetitive and fundamentally does not introduce anything new. At that point other topics took priority so I had no clear idea what I should do with the series. Recently I’ve just decided to skip over the boring stuff and go straight to the topic that I wanted to reach eventually anyway - native instrumentation.

To refresh your memory; we are implementing a coverage guided fuzzer. In order to gather the coverage we need to track the execution of the binary - by doing this we obtain information which parts of the program were executed and which ones were skipped. I’m aware that this is a terribly simplistic explanation but I assume that you already know that. If, however, you would like to go over the coverage gathering once again you can always read this great article written by h0mbre.

There are several methods of gathering coverage and previously we’ve used ptrace to collect the program trace with basic block resolution.

Resolution in this case means what is the granularity of the trace we are collecting. It can be as sparse as function or syscall we’ve reached or as fine as individual instructions. Chosen resolution impacts both the ability to guide mutation as well as, indirectly, the performance of the fuzzer.

Our chosen method had only one good characteristic - it was relatively easy to implement. Everything else was rather bad - performance was atrocious, we only gathered information about visited basic blocks, completely disregarding the order in which those blocks were visited or how many times. Today we are going to rectify at least some of the mentioned weaknesses.

Plan is as follows - we are going to alter the compilation stage of the program and insert small snippets of code. Those snippets will record every visited edge of the control flow graph and share this information through the shared memory with the fuzzing engine. More observant of you will immediately realize that we are essentially re-implementing AFL (and we are only 10 years late) and you will be right.

Shared memory is an operating system feature where two or more processes can have access to the same segment of memory. This allows the copy-less exchange of data and is exactly what we need in order to make our fuzzer fast.

Linux implements two interfaces for shared memory access - System V and POSIX. There are some differences between the two but, at least for our case they don’t matter that much. I’ve decided to use the POSIX variant because it’s newer and so there is no real compelling reason to stay with System V anymore

Fun fact: AFL uses System V. No idea why.

The basic routine when it comes to shared memory is that in one process you open the segment using smh_open(). Aforementioned function returns a file description. You can mmap() said descriptor as a readable/writable memory, so the program can make some use of it. The other process does exactly the same and as long as they agree on the segment name and certain flags they should be able to see the same memory fragment. For now we are going to skip over more advanced topics like mutexes, semaphores and queues.

We will begin by implementing two small C programs that will communicate with each other using this interface. First program called setter is presented below.

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define STORAGE_ID "/SHM_TEST"

#define STORAGE_SIZE 32

#define DATA "Hello, World! From PID %d"

// SETTER

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

char data[STORAGE_SIZE];

sprintf(data, "Hello from %d pid", getpid());

int fd = shm_open(STORAGE_ID, O_RDWR | O_CREAT, S_IRUSR | S_IWUSR);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("shm_open");

return 10;

}

int res = ftruncate(fd, STORAGE_SIZE);

if (res == -1) {

perror("ftruncate");

return 20;

}

void *addr = mmap(NULL, STORAGE_SIZE, PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if (addr == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap");

return 30;

}

// Writing to shared memory

size_t len = strlen(data) + 1;

memcpy(addr, data, len);

res = munmap(addr, STORAGE_SIZE);

if (res == -1) {

perror("munmap");

return 40;

}

fd = shm_unlink(STORAGE_ID);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("shm_unlink");

return 50;

}

return 0;

}

Going through the code we see that we’ve started with defining two constant values - the name of the shared segment as well as the length. It is important to keep that in sync between the setter and the getter otherwise we won’t be able to communicate. The size is also important - I don’t have to tell you what happens if you try to read or write to a memory that was not mapped correctly. Your fuzzer will produce its first crash, but probably not the one you would hope for.

As I’ve already mentioned - we need to open the shared segment first and we do that by using the shm_open(). Arguments are, in order, the name of the segment, flags and the mode. The name we’ve already mentioned but it’s worth remembering that those names can be seen as essentially file names. Using null bytes or slashes is generally discouraged. Flags control the way we are opening the segment - writable, readable or perhaps create it in case it does not exist. The mode only plays a role if we are creating the file and it sets proper permissions.

After successfully opening a share we can map it as a memory using the mmap(). Before we do that it is recommended that for newly created shares (O_CREAT flag) we call the ftruncate() to resize the share. Forgetting about this step and trying to read or write to the memory will leave you with a SIGBUS and interesting debugging adventure.

Speaking about the memory mapping - there are several flags controlling the behavior and the properties of such memory. It’s best to consult man or Michael Kerrisk book in order to get a full picture. This is especially important if you move between C and Rust because certain behaviors like MAP_ANONYMOUS might not exactly work as expected.

As for writing to said memory - mmap() returns a void pointer you can use freely. Well, almost freely as you need to remember about the size of the memory you’ve just mapped.

Last few lines are pretty easy to understand- being responsible programmers we do the cleanup by un-mapping the memory with munmap() and close the shared file using shm_unlink().

The getter code will be roughly the same except the memory reading part. Implementing it is left as an exercise to the reader.

Debugging tip: in the Linux system you can visit the

/dev/shmdirectory where you will find all active shared memory segments.

Now, if you run getter and setter at the same time (you can help yourself by strategically inserting sleep() into the setter) you will notice we have exchanged the string using the shared memory interface.

Knowing how the shared memory works we can start implementing our fuzzing engine. I didn’t want to overly complicate the one I wrote in the previous parts, therefore I’ve decided to start a new one from scratch. This will also give me a chance to implement it more cleanly this time. Or actually, a bit later because right now we are going to sprinkle code with occasional unwrap() and expect() to make reading it a bit easier.

We begin with the part responsible for running the fuzzing target and gathering the coverage information stored in the shared memory. You can see the entire code below.

use std::env;

use std::ffi::c_void;

use std::process::{Command, Stdio};

use nix::fcntl::OFlag;

use nix::sys::mman;

use nix::sys::mman::{MapFlags, ProtFlags};

use nix::sys::stat::Mode;

use nix::sys::wait::waitpid;

use nix::unistd::{ftruncate, Pid};

use core::num::NonZeroUsize;

const MAP_NAME: &str = "/fuzz.map";

const STORAGE_SIZE: i64 = 64 * 1024;

fn main() {

let runtime = env::args().nth(1);

// open shared memory

let shm_open_flags = OFlag::O_CREAT | OFlag::O_RDWR;

let shm_open_mode = Mode::S_IRUSR | Mode::S_IWUSR;

let mem = mman::shm_open(MAP_NAME, shm_open_flags, shm_open_mode)

.expect("Failed to open shared memory");

// resize the file to L1 cache size

ftruncate(&mem, STORAGE_SIZE).expect("Unable to resize file");

// map the shared memory as a memory region

let mmap_prot = ProtFlags::PROT_READ | ProtFlags::PROT_WRITE;

let mmap_flags = MapFlags::MAP_SHARED;

let var = unsafe {

mman::mmap(

None,

NonZeroUsize::new(STORAGE_SIZE as usize).unwrap(),

mmap_prot,

mmap_flags,

Some(&mem),

0,

)

.unwrap()

} as *const u8;

if let Some(r) = runtime {

println!("Running fuzz target: {}", r);

let p = Command::new(r)

.arg("ABC")

.stdout(Stdio::null())

.stderr(Stdio::null())

.spawn()

.expect("[!] Failed to run process:");

let pid = Pid::from_raw(p.id() as i32);

match waitpid(pid, None) {

Ok(status) => {

println!("[{}] Got status: {:?}", pid, status);

println!("Reading from the shared memory...");

let trace = unsafe {

std::slice::from_raw_parts(var, STORAGE_SIZE as usize)

};

for x in 0..128 {

if x != 0 && x % 32 == 0 {

println!();

}

print!("{:02x} ", trace[x]);

}

println!();

}

Err(e) => {

eprintln!("Error waiting for pid: {:?}", e);

}

};

}

unsafe { mman::munmap(var as *mut c_void, STORAGE_SIZE as usize).unwrap() };

mman::shm_unlink(MAP_NAME).unwrap();

}

For starters, we are going to use the nix crate to easily access several system functions that we are going to need. There are several elements that you should already be familiar with, like the usage of mman::shm_open(), ftruncate() and mman:mmap() to, respectively, open the memory share, resize it to defined size and map it as a variable. Figuring out the flags and modes also shouldn’t take you too much time. Just like in our programs written in C, cleanup operations are handled by mman::munmap() and mman::shm_unlink().

First thing that requires explanation is the number of unsafe annotations we were forced to use. This, however, is hardly a surprise - after all we are essentially operating on a raw pointer that our program knows nothing about. As you can imagine such pointers don’t translate well into the Rust world so we need to convert it to something that the rest of the program will be able to use. We do this by calling std::slice::from_raw_parts() and supplying the starting address and the size in bytes. Thanks to this nice function we actually end up with a slice of u8 values we can freely read from. Of course - this comes with a huge risk hidden under yet another unsafe annotation. One thing you might be wondering is - but what about the type? If we look back at how we have mapped the memory you will see that we cast the resulting value into a u8 pointer. Rust is smart enough to infer that the slice we will be operating on contains values of this type.

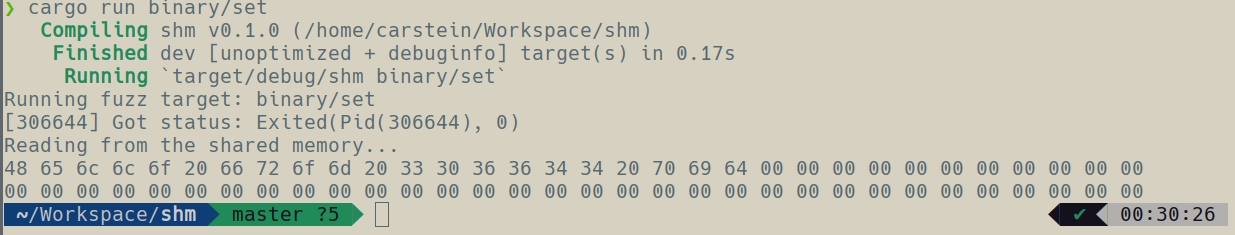

Rest of the fuzzing engine, for now, is not very interesting - we basically just run the provided target binary and wait for it to finish so we can read the shared memory. Now, if you adjust the C program that we have written previously so the shared memory name and size matches things should work together. Running the fuzzer with the setter as an argument should result in printing out a hex representation of the shared memory modified by the child process. Just like on this image

Now we are reaching the hardest part - how to convince the compiler to insert a set of instructions of our choosing into the binary composed of the source we have very little intention of modifying. What would be previously a 12-part series of compiler internals (that would probably be way over my head and cost me sanity), thanks to the great people responsible for clang and llvm, will be just a few lines of code and one weird makefile. Turns out that clang already comes with the interface for writing code instrumentation. Lets see how this works in practice by reading this simple code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <sanitizer/coverage_interface.h>

extern void __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard_init(uint32_t *start,

uint32_t *stop) {

static uint64_t N; // Counter for the guards.

if (start == stop || *start) return; // Initialize only once.

printf("INIT: %p %p\n", start, stop);

for (uint32_t *x = start; x < stop; x++)

*x = ++N; // Guards should start from 1.

}

extern void __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard(uint32_t *guard) {

if (!*guard) return; // Duplicate the guard check.

printf("Edge: %p %x\n", guard, *guard);

}

We see that there are two major functions that we define: __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard_init() and __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard(). Let’s start with the latter one - this function will be inserted by the compiler into every edge in the control flow and the *guard will point to a unique memory location - different for every edge. If you are wondering what can we find if we follow this pointer it’s time we look into the other function. It gets inserted by the compiler as a module constructor into every DSO. The start and stop parameters mark the area where all the guards for the entire binary are located and we can set those guards to whatever values we want. In our case I’ve simply gone for the incremental values.

Now, in our case we went for a fairly simple approach where we instrument only took a branch, but if you look at the documentation there are multiple other options - you can instrument other operations like comparison, store or dereferencing a pointer. Don’t let the Experimental labels discourage you and, well, experiment. I sense that some interesting ways to track coverage might emerge from this approach.

Knowing what we want to write it’s time we look at how to combine it with some other program. Admittedly, I haven’t had a time yet to use it against some real project as I was mostly working with samples I wrote on my own. Still, the same principles will apply and probably modifying at least one Makefile is unavoidable. In the meantime let us look at the one I wrote for the purpose of this article.

CC=clang

CFLAGS=-Wall -lrt

CFLAGS_INSTR=-fsanitize-coverage=trace-pc-guard,no-prune

## Universal rule for all cases

case_%: sample_%.o instr_%.o

$(CC) $^ -o $@

sample_%.o: sample_%.c

$(CC) $^ $(CFLAGS_INSTR) -c

instr_%.o: instr_%.c

$(CC) $^ -o $@ -c

## Cleanup

.PHONY: clean

clean:

rm -rf *.o

I’m well aware that this one would not win any awards. Still, it does its job and I was semi-proud to make it work for all the samples and instrumentation variants I was writing without adding extra targets. Anyhow, we should start the analysis by looking at the instr_%.o target. For the instr_1.o file the compilation will resolve into clang instr_1.c -o instr_1.o -c. For those unfamiliar with the -c argument - it will compile the code into an object but without a final linking stage. We do the same to our sample code (in this case stored in sample_1.c) but in this case we provide a few additional flags like -fsanitize-coverage=trace-pc-guard,no-prune. This instructs the compiler to insert appropriate instrumentation where necessary. In the last stage we link both files together producing the final binary - case_1.

You might be wondering why I have not provided sample code that we add the instrumentation to. I believe that everybody should try to instrument their code of choosing. In my case I have a sample with a series of nested ifs that look for a certain word passed as a program argument.

One thing worth explaining is the no-prune option. Looking at the binary compiled without it might surprise you a little bit when some of the edges will be left without instrumentation. This is just an effect of the compiler trying to reason about redundant entries. In general I compile my code without any instrumentation pruning just to be sure everything is covered, but this is a fairly interesting topic that deserves at least a short note on its own.

We’ve reached the phase where we adjust the instrumentation code to work with our fuzzer. We can see how it is done in the code below.

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sanitizer/coverage_interface.h>

#define STORAGE_ID "/fuzz.map"

#define STORAGE_SIZE 64 * 1024

void *addr = NULL;

void unmap() {

munmap(addr, STORAGE_SIZE);

}

extern void __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard_init(uint32_t *start,

uint32_t *stop) {

// Setup guards

static uint64_t N; // Counter for the guards.

if (start == stop || *start) return; // Initialize only once.

for (uint32_t *x = start; x < stop; x++)

*x = ++N; // Guards should start from 1.

// Setup shared memory

int fd = shm_open(STORAGE_ID, O_RDWR, S_IRUSR | S_IWUSR);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("Failed to open shm share");

return;

}

addr = mmap(NULL, STORAGE_SIZE, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if (addr == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("Failed to mmap file");

return;

}

atexit(unmap);

}

extern void __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc_guard(uint32_t *guard) {

if ((size_t *)addr && *guard) {

// place a bit in a map

uint8_t *map_ptr = ((uint8_t *)addr + *guard);

*map_ptr += 1;

printf("writing to: %p\n", map_ptr);

}

}

There are several elements that should be already known to you like initializing guards and obtaining a shared memory segment. The only addition here is the function responsible for un-mapping the memory when the program exits. Because clang instrumentation does not offer a destruction function we have to register one on our own using atexit().

The edge guard function is a bit more interesting than the previous one but still fairly primitive. Remembering that we have initialized each guard value with incremental number we can basically treat our shared memory segment as a simple bitmap and mark each edge as a single byte (not bit, because we are also counting number of occurrences). This approach will spectacularly fail in the program with more than 64k branches, but I think we are still far away from that point.

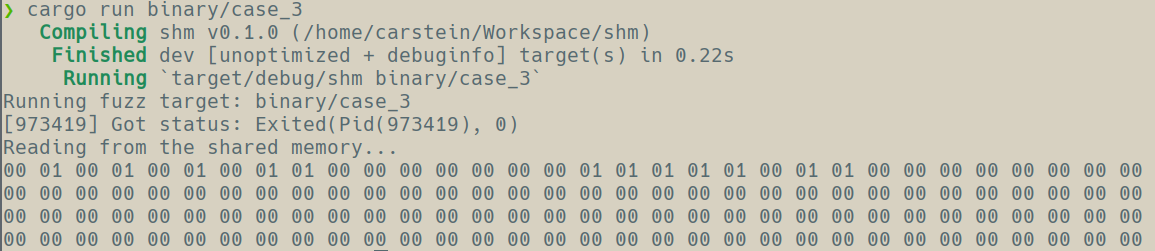

Running the instrumented code under the fuzzer produces the following output, clearly demonstrating that we have managed to successfully implement native code instrumentation.

We have a working mechanism to track coverage and report the results via a shared memory. There are few things that need improvement but we are already in a pretty good place. First of all, we are already tracking coverage on the branch level so we don’t have to do some weird bit shifting on basic block id to get this information. Second, with branch coverage pruning mechanism on by default we are mostly tracking the branches that matter so the 64k branch limit is far from being a blocker. Still, in the next parts I would like to prevent our instrumentation from crashing if there are more branches. In addition, with the current statically encoded shared segment name we can only have one fuzzer and one target running and I would like to amend that in the future version.

Besides that, in the next part you should expect all the other elements of the fuzzer coming together. If time and space permits I would like to focus on performance measuring and perhaps even profiling.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh