This post is also available i 2022-11-21 19:0:27 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:47 收藏

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Unit 42 investigated several incidents related to the Luna Moth/Silent Ransom Group callback phishing extortion campaign targeting businesses in multiple sectors including legal and retail. This campaign leverages extortion without encryption, has cost victims hundreds of thousands of dollars and is expanding in scope.

By design, this style of social engineering attack leaves very few artifacts because of the use of legitimate trusted technology tools to carry out attacks. However, Unit 42 has identified several common indicators implying that these attacks are the product of a single highly organized campaign. This threat actor has significantly invested in call centers and infrastructure that’s unique to each victim.

Cybersecurity awareness training is the most effective defense against these stealthy and discreet attacks. However, Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection from the attacks discussed in this blog through the Next-Generation Firewall and Cortex XDR detecting data exfiltration or connections to suspicious networks.

Table of Contents

What Is Callback Phishing?

The Typical Callback Phishing Attack Chain

Luna Moth Campaign Analysis

Prevention and Detection

Conclusion

Additional Resources

What Is Callback Phishing?

Callback phishing, also referred to as telephone-oriented attack delivery (TOAD), is a social engineering attack that requires a threat actor to interact with the target to accomplish their objectives. This attack style is more resource intensive, but less complex than script-based attacks, and it tends to have a much higher success rate.

In the past, threat actors associated with the Conti group have had great success with this attack style in the BazarCall campaign. Unit 42 has been tracking these types of attacks since 2021. Early iterations of this attack focused on tricking the victim into downloading the BazarLoader malware using documents with malicious macros.

This new campaign, which Sygnia has attributed to a threat actor dubbed "Luna Moth," does away with the malware portion of the attack. In this campaign, attackers use legitimate and trusted systems management tools to interact directly with a victim’s computer, to manually exfiltrate data to be used for extortion. As these tools are not malicious, they’re not likely to be flagged by traditional antivirus products.

Please note that the tools named in this post are legitimate. Threat actors often abuse, take advantage of or subvert legitimate products for malicious purposes. This does not imply a flaw or malicious quality to the legitimate product being abused.

The Typical Callback Phishing Attack Chain

The initial lure of this campaign is a phishing email to a corporate email address with an attached invoice indicating the recipient’s credit card has been charged for a service, usually for an amount under $1,000. People are less likely to question strange invoices when they are for relatively small amounts. However, if people targeted by these types of attacks reported these invoices to their organization’s purchasing department, the organization might be better able to spot the attack, particularly if a number of individuals report similar messages.

The phishing email is personalized to the recipient, contains no malware and is sent using a legitimate email service. These phishing emails also have an invoice attached as a PDF file. These features make a phishing email less likely to be intercepted by most email protection platforms.

The attached invoice includes a unique ID and phone number, often written with extra characters or formatting to prevent data loss prevention (DLP) platforms from recognizing it. When the recipient calls the number, they are routed to a threat actor-controlled call center and connected to a live agent.

Under the guise of canceling the subscription, the threat actor agent guides the caller through downloading and running a remote support tool to allow the attacker to manage the victim’s computer. This step usually generates another email from the tool’s vendor to the victim with a link to start the support session.

The attacker then downloads and installs a remote administration tool that allows them to achieve persistence. If the victim does not have administrative rights on their computer, the attacker will skip this step and move directly to finding files for exfiltration.

The attacker will then seek to identify valuable information on the victim’s computer and connected file shares, and they will quietly exfiltrate it to a server they control using a file transfer tool.

In this way, the threat actor is able to compromise organizational assets through a social engineering attack on an individual.

After the data is stolen, the attacker sends an extortion email demanding victims pay a fee or else the attacker will release the stolen information. If the victim does not establish contact with the attackers, they will follow up with more aggressive demands. Ultimately, attackers will threaten to contact victims’ customers and clients identified through the stolen data, to increase the pressure to comply.

Luna Moth Campaign Analysis

Unit 42 has responded to multiple cases related to a single campaign that occurred from mid-May to late October 2022. ADVIntel attributes this campaign to a threat actor dubbed Silent Ransom with ties to Conti. While Unit 42 cannot confirm Silent Ransom’s tie to Conti at this time, we are monitoring this closely for attribution.

These cases show a clear evolution of tactics that suggests the threat actor is continuing to improve the efficiency of their attack. Cases analyzed at the beginning of the campaign targeted individuals at small- and medium-sized businesses in the legal industry. In contrast, cases later in the campaign indicate a shift in victimology to include individuals at larger targets in the retail sector.

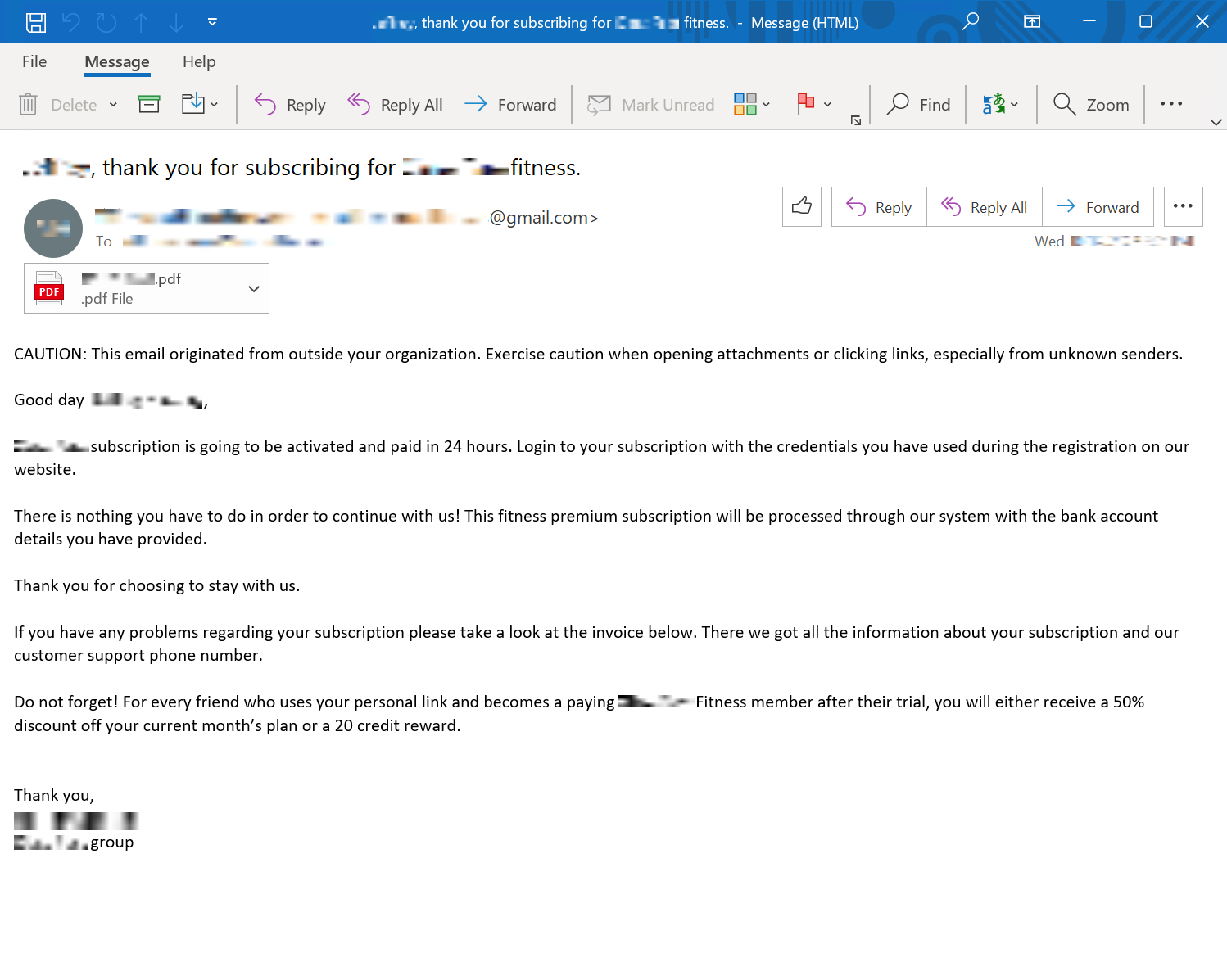

During the initial campaign, the phishing email frequently originated from an address using the format FirstName.LastName.[SpoofedBusiness]@gmail[.]com as seen in Figure 1. The attacker often spoofs the names of obscure athletes for these email addresses.

Unit 42 has also observed emails with the format [RandomWords]@outlook[.]co.th.

The wording in the body of the phishing email has changed throughout the campaign. This was likely done to thwart email protection platforms. Regardless of what wording was used, the email always indicated the victim is responsible for the charges detailed in the attached invoice.

PDF documents containing an invoice number were attached to the phishing emails. Unit 42 observed fake invoices spoofing both an online class platform and a health club aggregator in this campaign.

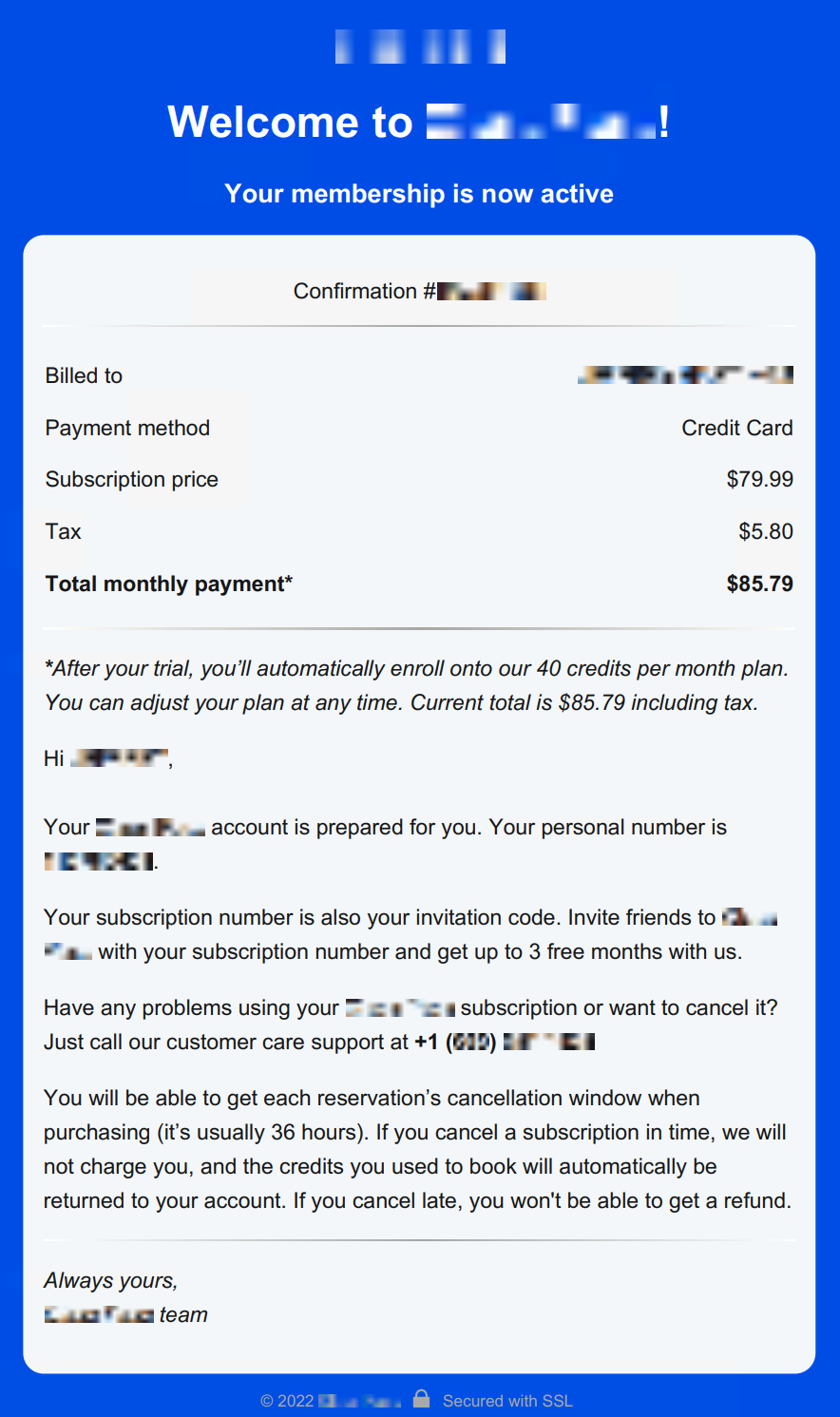

Early incidents used a logo from one of the spoofed businesses at the top of the invoice. Later cases replaced this with the simple header welcoming the target to the second spoofed business on a plain blue background, as shown in Figure 2. Each invoice features a nine- or 10-digit confirmation number near the top, which is also incorporated into the filename. When the recipient contacts the threat actor, this confirmation number is used to identify them.

Early iterations of the extortion campaign recycled phone numbers, but later attacks either used a unique phone number per victim, or victims would be presented with a large pool of available phone numbers in the invoice.

The attacker registered all of the numbers they used via a Voice over IP (VoIP) provider. When the victim called one of the attacker’s numbers, they were placed into a queue and eventually connected with an agent who sent a remote assist invitation for the remote support tool Zoho Assist.

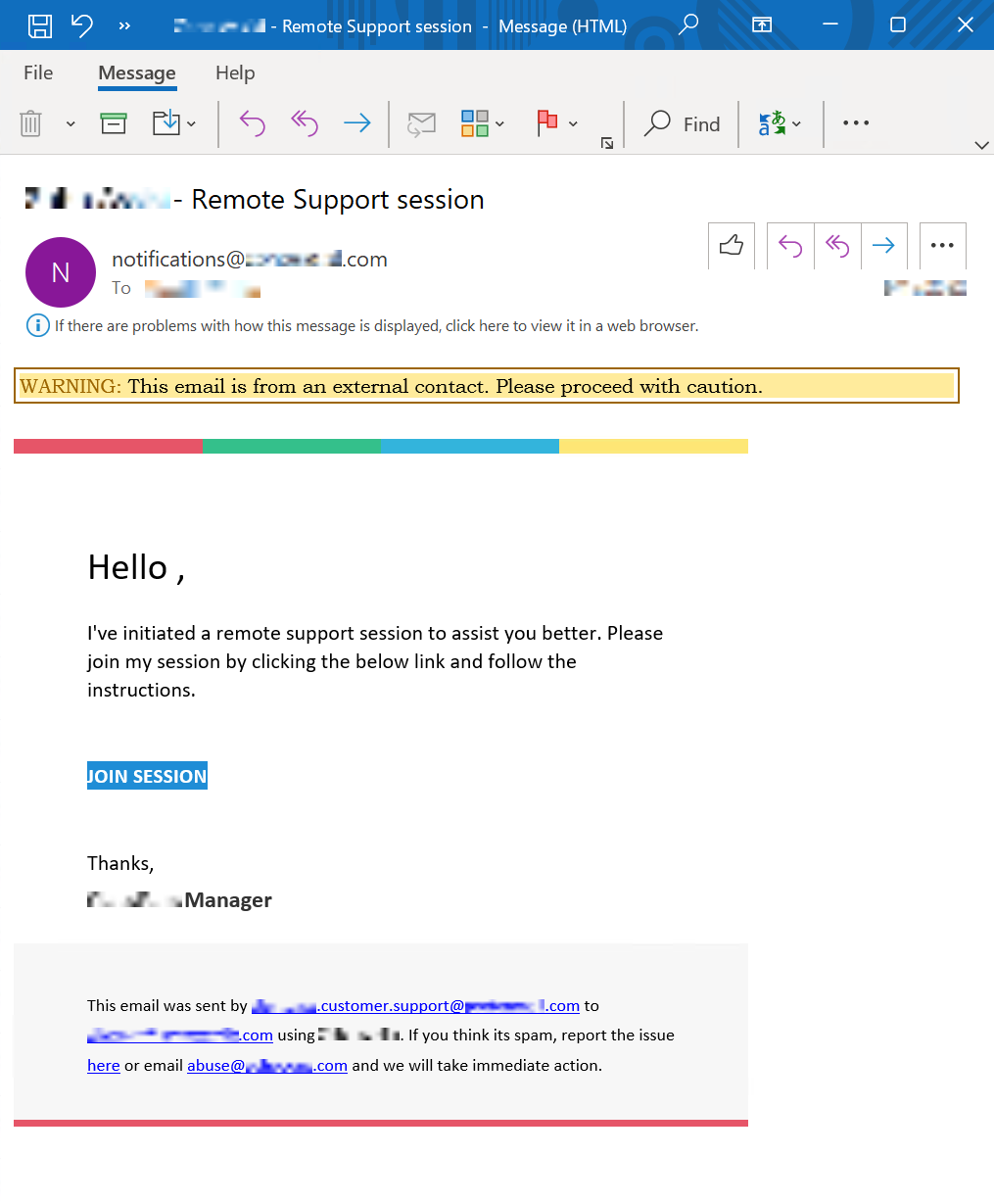

The footer of these invitation emails (shown in Figure 3) revealed the email address the threat actor used to register with Zoho. In most incidents, the attacker chose an address from an encrypted email service provider to masquerade as the same vendor used in the fake invoice.

Once the victim connected to the session, the attacker took control of their keyboard and mouse, enabled clipboard access, and blanked out the screen to hide their actions.

Once the attacker blanked the screen, they installed remote support software Syncro for persistence and open source file management tools Rclone or WinSCP for exfiltration. Early cases also included remote management tools Atera and Splashtop, but recently the attacker appears to have tightened their toolset.

In cases where the victim did not have administrative rights to their operating system, the attacker skipped installing software to establish persistence. Attackers instead downloaded and executed WinSCP Portable, which does not require administrative privileges and is able to run within the user’s security context.

In cases where the attacker established persistence, exfiltration occurred hours to weeks after initial contact. Otherwise, the attacker only exfiltrated what they could during the call. The attacker exfiltrated data shortly before the attack.

The domains used early in the campaign were random words with a top-level domain (TLD) of .xyz. Later in the campaign, domains consistently followed the format of [5 letters].xyz. All observed domains fell into the 192.236.128[.]0/17 network range.

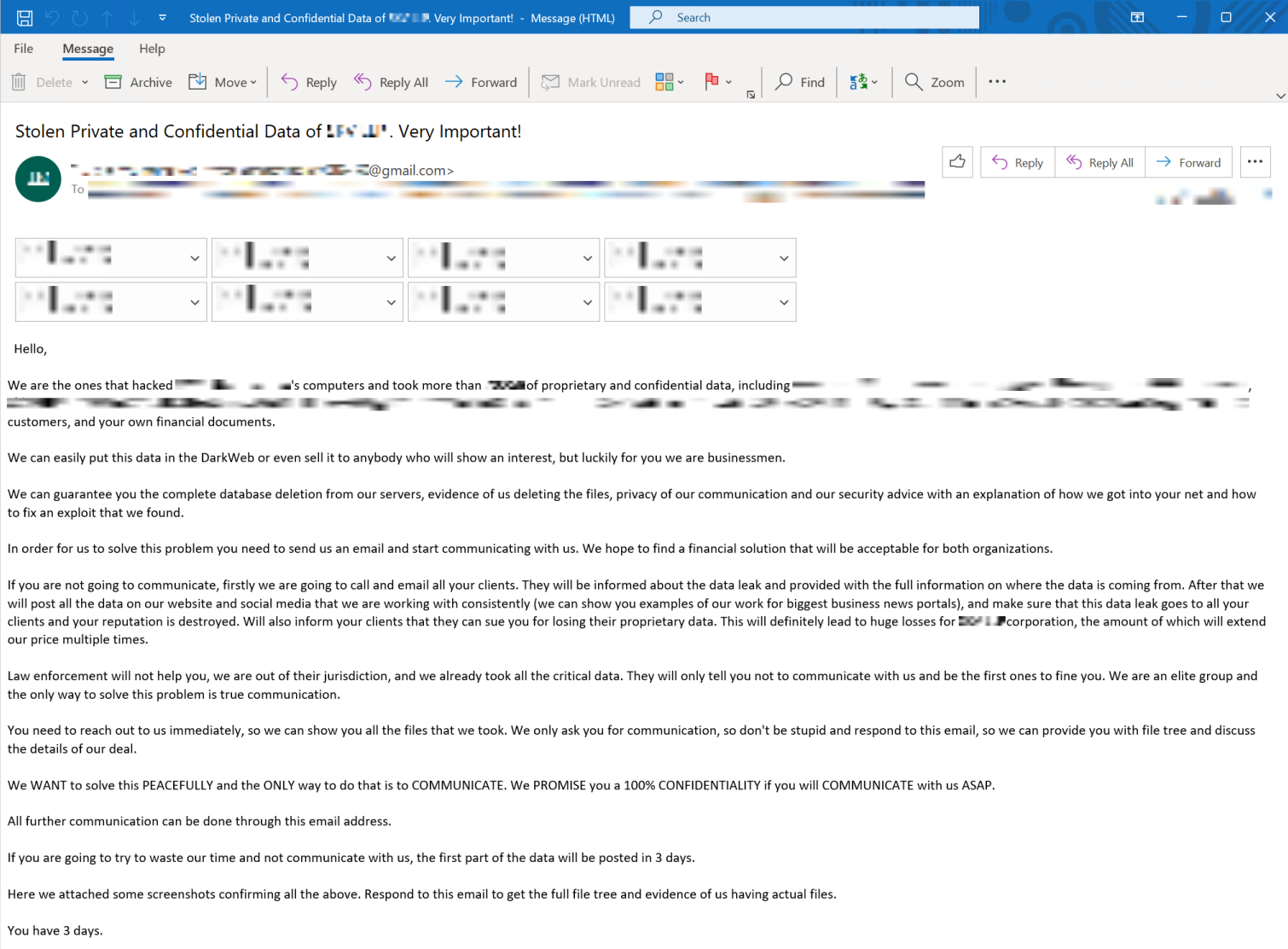

Exfiltration was followed with an extortion email, as shown in Figure 4. Like in other templates used in this campaign, the wording and format in the extortion email has evolved over time. In the cases Unit 42 investigated, the attacker claimed to have exfiltrated data in amounts ranging from a few gigabytes to over a terabyte.

The threat actor created unique Bitcoin wallets for each victim’s extortion payments. These wallets contained only two or three transactions and were emptied immediately after funding.

Attacker’s monetary demands ranged from 2-78 BTC. They researched the target organization’s revenue and used it to justify this extortion amount. However, attackers were quick to offer discounts of approximately 25% for prompt payment.

Paying the attacker did not guarantee they would follow through with their promises. At times they stopped responding after confirming they had received payment, and did not follow through with negotiated commitments to provide proof of deletion.

Prevention and Detection

The threat actors behind this campaign have taken great pains to avoid all non-essential tools and malware, to minimize the potential for detection. Since there are very few early indicators that a victim is under attack, employee cybersecurity awareness training is the first line of defense.

People should always be cautious of messages that invoke fear or a sense of urgency. Do not respond directly to suspicious invoices. Contact the requester directly via the channels made available on the vendor’s official website. People should also consult internal support channels before downloading or installing software on their corporate computers.

The second line of defense against this attack type is a robust security technology stack designed to detect behavioral anomalies in the environment. Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection from the attacks discussed in this blog through the Next-Generation Firewall and Cortex XDR detecting data exfiltration or connections to suspicious networks.

Conclusion

Unit 42 expects callback phishing attacks to increase in popularity due to the low per-target cost, low risk of detection and fast monetization. While groups that can establish infrastructure to handle inbound calls and identify sensitive data for exfiltration are likely to dominate the threat landscape initially, a low barrier to entry makes it probable that more threat actors will enter the fray.

Common observables suggest a pervasive multi-month campaign that is actively evolving. Therefore, organizations in currently targeted industries, such as legal and retail, should be particularly vigilant to avoid becoming victims.

All organizations should consider strengthening cybersecurity awareness training programs with a particular focus on unexpected invoices, as well as requests to establish a phone call or to install software. Additionally, expand investments in cybersecurity tools designed to detect and prevent anomalous activity, such as installing unrecognized software or exfiltrating sensitive data.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Additional Resources

- BazarCall Method: Call Centers Help Spread BazarLoader Malware

- Luna Moth: The Threat Actors Behind Recent False Subscription Scams

- “BazarCall” Advisory: Essential Guide to Attack Vector that Revolutionized Data Breaches

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh