This post is also available i 2022-6-4 04:0:0 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:28 收藏

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

REvil has emerged as one of the world’s most notorious ransomware operators. In summer 2021, it extracted an $11 million payment from the U.S. subsidiary of the world’s largest meatpacking company based in Brazil, demanded $5 million from a Brazilian medical diagnostics company and launched a large-scale attack on dozens, perhaps hundreds, of companies that use IT management software from Kaseya VSA.

While REvil (which is also known as Sodinokibi) may seem like a new player in the world of cybercrime, Unit 42 has been monitoring the threat actors tied to this group for three years. We first encountered them in 2018 when they were working with a group known as GandCrab. At the time, they were mostly focused on distributing ransomware through malvertising and exploit kits, which are malicious advertisements and malware tools that hackers use to infect victims through drive-by downloads when they visit a malicious website.

That group morphed into REvil, grew and earned a reputation for exfiltrating massive data sets and demanding multimillion dollar ransoms. It is now among an elite group of cyber extortion gangs that are responsible for the surge in debilitating attacks that have made ransomware among the most pressing security threats to businesses and nations around the globe.

Updated June 3, 2022: In October 2021, REvil went offline at least in part due to major multi-government entities pursuing the group. The absence, however, was apparently short lived. On April 20, 2022, REvil’s old leak site came back online. We’ve updated our original report on REvil’s activity to include insights on the most recent samples and attacks – though we note that it is not yet clear whether the threat actors behind this activity are actually members of the original group or if this is REvil under a new administration. The new information is included under the header “REvil in 2022.”

Palo Alto Networks WildFire, Threat Prevention and Cortex XDR detect and prevent REvil ransomware infections.

If you think you may have been impacted, please get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

REvil in 2022: New Observations of Ransom Notes, Leak Site, Payment Site and More

REvil, one of the most prolific ransomware groups of 2021, went offline in October 2021. The dissolution of REvil was due to major multi-government entities pursuing the group’s operations, with arrests occurring, infrastructure seized, the disappearance of ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) leadership and general mistrust between members of the group

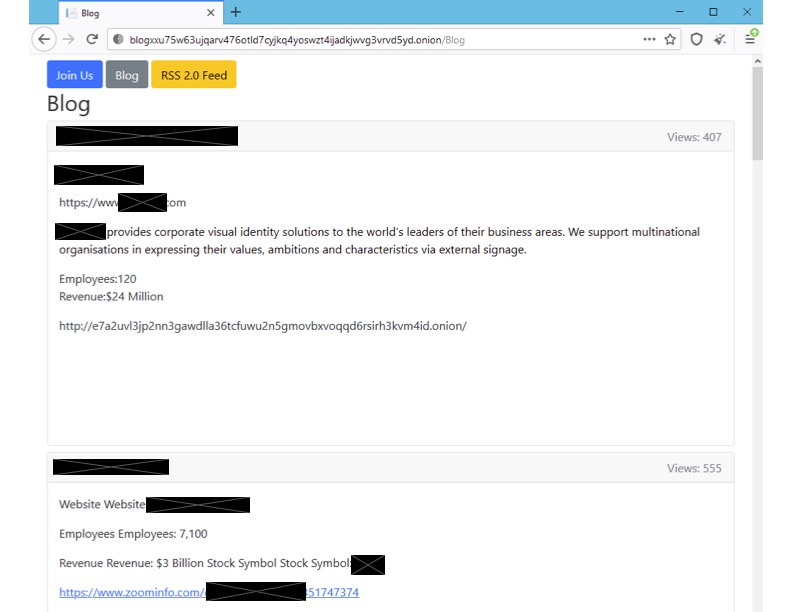

On April 20, 2022, REvil’s old leak site came back online and started redirecting visitors to a new Onion address, listing new and previous victims. Of particular note, the new site also looks a bit different from the original “Happy Blog” led by the original REvil group – for example, the new site includes an RSS 2.0 feed and a “Join Us” section for active affiliate recruiting. Additionally, the proof of concept links are offline or removed for old victims, leading Unit 42 to believe that the website was revived from a backup and it didn’t update any of the content inside the posts. It is also possible that the blog is being recreated by another group – not necessarily the same threat actors who claimed the work of REvil before.

During early May, we noticed new alleged victim organizations being listed and then removed from the site numerous times. Typically, when an organization is removed from the site, it’s because they have paid the ransom, but this does not appear to be the case here. Instead, the same potential victims were added and then removed several times. The organizations were an India-based oil organization, a U.S.-based education organization and a France-based sign manufacturer. We observed the site being unstable at times – in some instances showing a blank page with no victims listed.

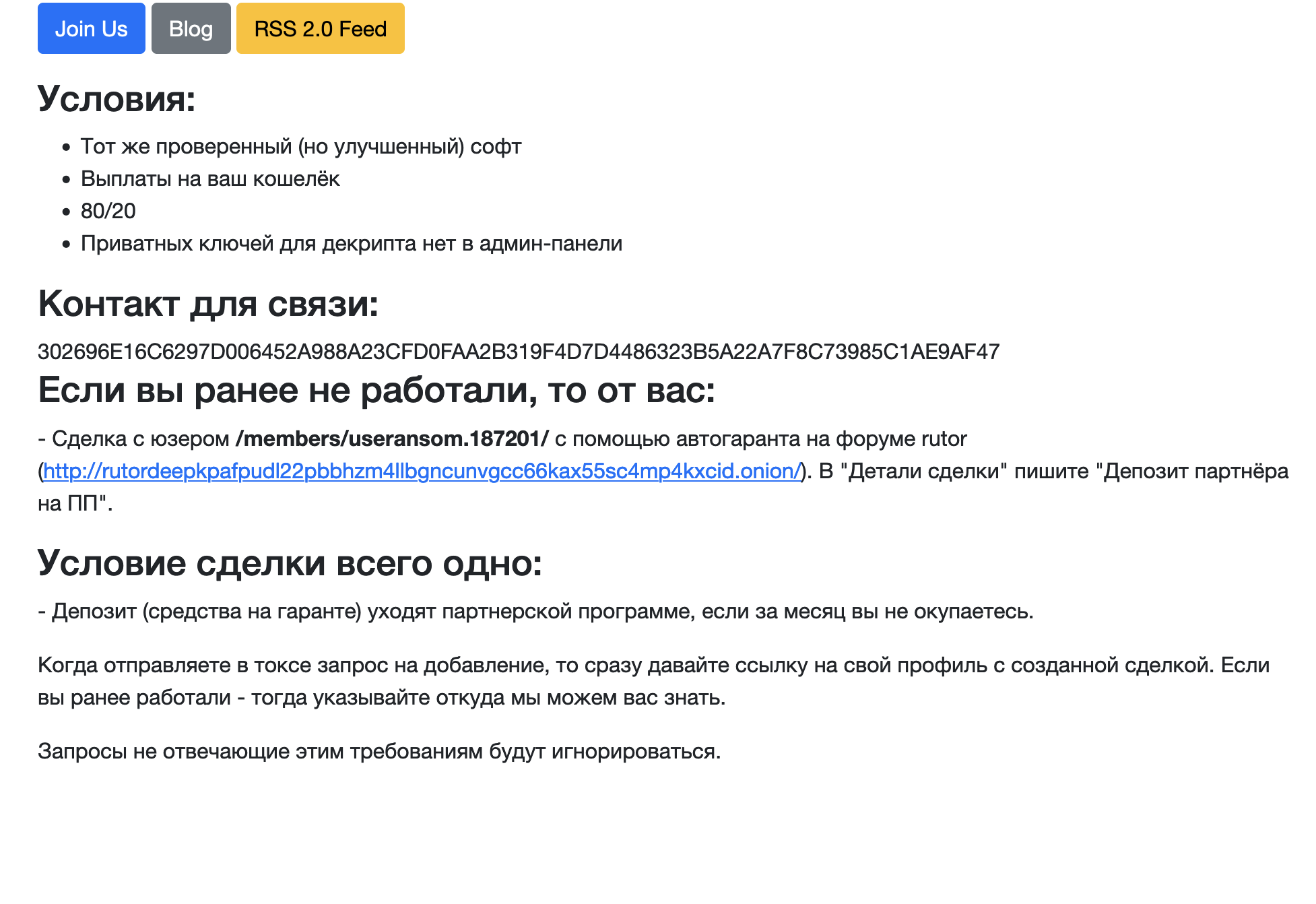

The recruiting section on the revived leak site at first directed victims to RuTOR, a known Russian-speaking forum marketplace typically selling illicit goods, leveraging the platform's automated escrow service. An affiliate interested in joining this iteration of REvil was asked to deposit money as part of an automated escrow agreement with an REvil member. Once this process was complete, the affiliate would then get an invite to the group.

We find the use of RuTOR interesting, since it’s not particularly known for ransomware operators, unlike other forums such as RAMP, Exploit or XSS – where posts seeking “security services” such as pentesters often turn out to be ransomware-related.

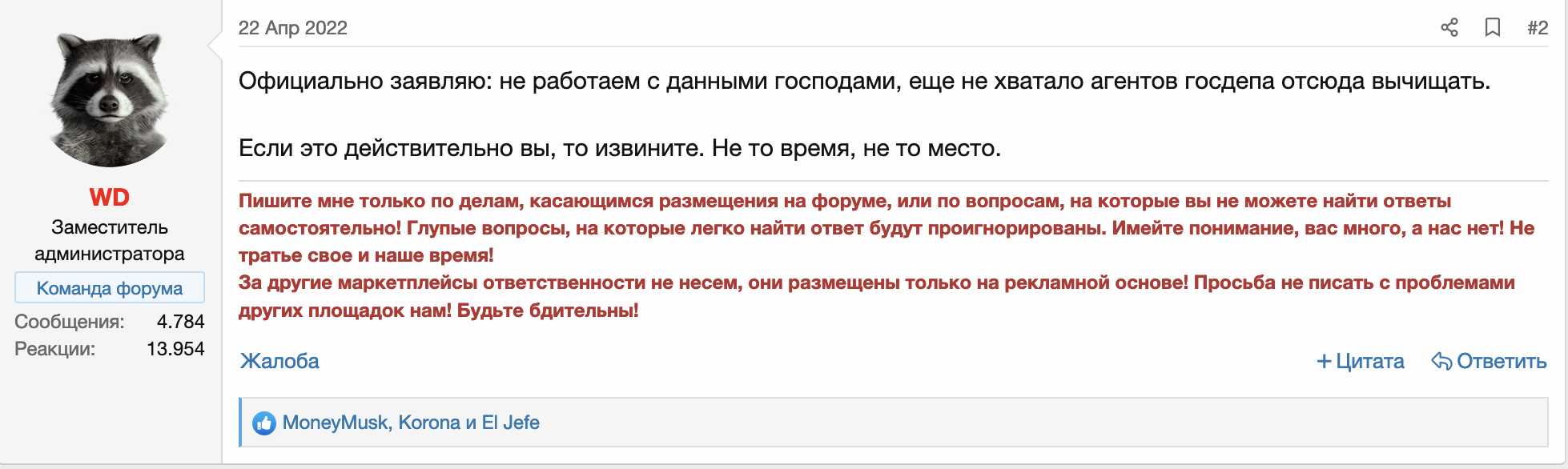

On April 22, we observed a post on RuTOR titled, “REvil’s TOR Sites are suddenly up and running again,” which prompted a response from WD, one of the RuTOR administrators, declaring that REvil is not welcome on the forum (Figure 3).

It’s worth noting that shortly after this post was made public, the threat actor behind the REvil leak site removed mentions of RuTOR from the leak site – from then on only leveraging TOX Chat for communication. The account useransom that was being used on RuTOR got suspended.

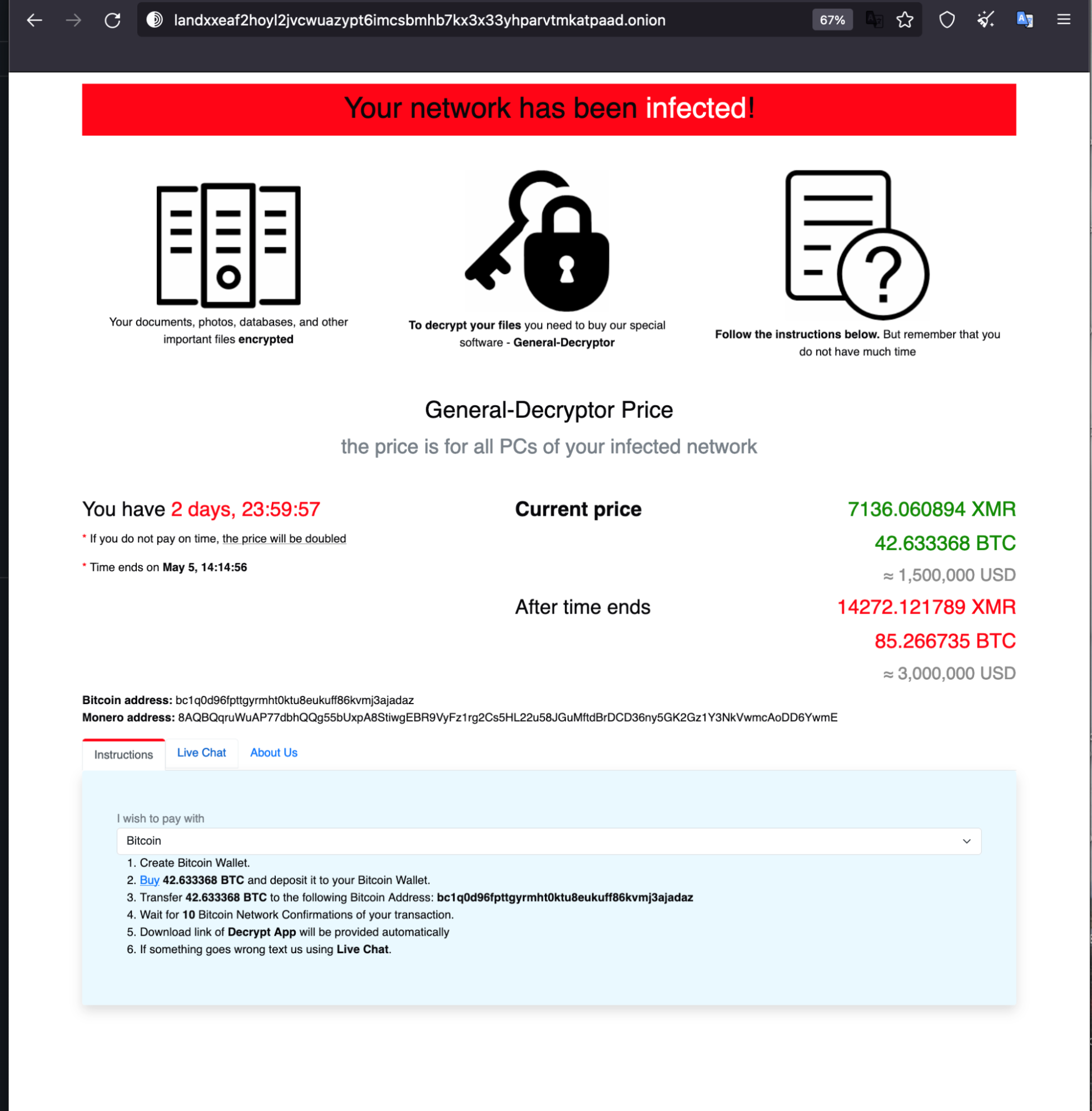

On April 29, a REvil/Sodinokibi variant emerged in VirusTotal, initially reported by a researcher at AVAST. The observed sample (SHA256: 0c10cf1b1640c9c845080f460ee69392bfaac981a4407b607e8e30d2ddf903e8) was compiled on April 26, three days before the researchers encountered the sample in the wild. This is believed to be a new version of the REvil sample. This sample includes various updates compared to previous REvil samples, including adding pointers to the new leak site and payment site. (The payment site appears similar to previous versions.)

The sample also has a new field embedded in its JSON configuration, named accs. This field had accounts associated with two different organizations – one in Taiwan and one in Israel. At the time, those two organizations hadn’t been observed on the new REvil leak site, which could indicate they were perhaps victims being actively targeted.

The “ransomware” sample in fact only seems to behave like ransomware – it appears to encrypt files but doesn’t actually do so. The analyzed sample only renames existing files with a random extension – removing the extension will restore the file back to its original state (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Changing extensions on renamed files.

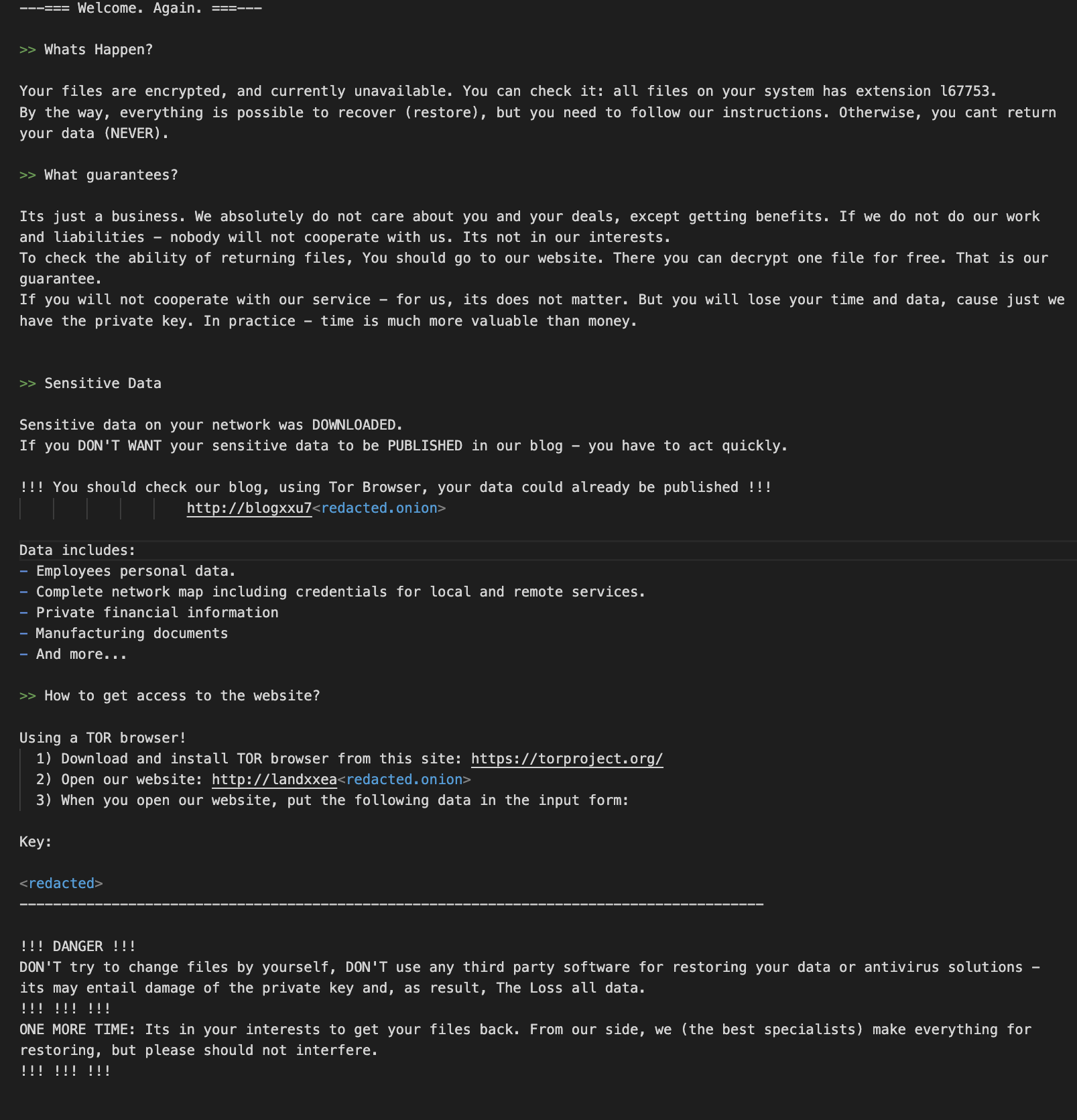

The ransom note is almost identical to the original used by this group; notable differences include:

- Removal of the clearnet site that was previously included – decoder[.]re

- New updated domains added, pointing to new infrastructure

- Additional comments from the threat actors, such as a “Sensitive Data'' section that is identical to the one seen in the BlackCat ransom note.

The similarity to the BlackCat ransom note isn’t surprising – ransomware groups are known to copy each other's ransom notes from time to time (See Figure 5 for the full REvil note).

Their new payment site also seems to be similar to what REvil used in the past.

In the case of the April 29 sample, the requested ransom is $1.5 million. As seen in previous REvil cases, the ransom request doubles if payment is not performed within the established time frame. We looked for transactions on the BTC wallet address posted on the payment site. As of the writing of this updated report, there haven’t been any transactions made to that wallet address.

It’s still too early to say whether the threat actors behind this activity are actually members of the original group or if this is REvil under a new administration.

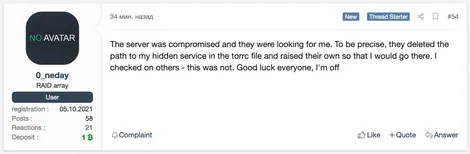

The “return” of the REvil/Sodinokibi name is not surprising; REvil had quite a reputation, built from three years of active ransomware activity. That being said, the REvil brand also has been tarnished. The group has gone offline multiple times due to high-profile attacks that led to law enforcement pursuit – and lost the trust of affiliates in the process. With the sudden disappearance of prominent leaders – Unknown(aka UNKN) in July and 0_neday shortly after in October 2021 – REvil leadership wasn’t able to restore confidence.

Even with the apparent return of REvil, other cybercriminals are skeptical, and some suspect law enforcement is behind it. Recruiting with such a reputation may be a bit difficult, and this is one of the main reasons why ransomware groups rebrand.

Regardless of who is behind the reemergence of this group, we continue to recommend that organizations prepare themselves to combat any ransomware that emerges. As always, the best time to prepare for a ransomware incident is before it happens.

Ransomware as a Service

REvil is one of the most prominent providers of ransomware as a service (RaaS). This criminal group provides adaptable encryptors and decryptors, infrastructure and services for negotiation communications, and a leak site for publishing stolen data when victims don’t pay the ransom demand. For these services, REvil takes a percentage of the negotiated ransom price as their fee. Affiliates of REvil often use two approaches to persuade victims into paying up: They encrypt data so that organizations cannot access information, use critical computer systems or restore from backups, and they also steal data and threaten to post it on a leak site (a tactic known as double extortion).

Threat actors behind REvil operations often stage and exfiltrate data followed by encryption of the environment as part of their double extortion scheme. If the victim organization does not pay, REvil threat actors typically publish the exfiltrated information. We have observed threat actors who are clients of REvil focus on attacking large organizations, which has enabled them to obtain increasingly large ransoms. REvil and its affiliates pulled in an average payment of about $2.25 million during the first six months of 2021 in the cases that we observed. The size of specific ransoms depends on the size of the organization and type of data stolen. Further, when victims fail to meet deadlines for making payments via bitcoin, the attackers often double the demand. Eventually, they post stolen data on the leak site if the victim doesn’t pay up or enter into negotiations.

2021 Trends – Something Old, Something New

Unit 42 has worked over a dozen REvil ransomware cases so far this year. While some of the tactics cited in our 2021 Unit 42 Ransomware Threat Report have remained the same, we have seen a few deviations from REvil’s standard attack lifecycle. For a quick reference, we have generated Actionable Threat Objects and Mitigations (ATOMs) to display REvil’s tactics, techniques, procedures and other indicators of compromise (IOCs).

How REvil Threat Actors Gain Access

REvil threat actors continue to use previously compromised credentials to remotely access externally facing assets through Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). Another commonly observed tactic is phishing leading to a secondary payload. However, we also observed a few unique vectors that relate to the recent Microsoft Exchange Server CVEs, as well as a case that involved a SonicWall compromise. Below are the five unique entry vectors observed thus far in 2021.

- A user downloads a malicious email attachment that, when opened, initiates a payload that downloads and installs a QakBot variant of malware. In at least one case, the version of QakBot we observed collected emails stored on the local system, archived them and exfiltrated them to an attacker controlled server.

- In one instance, a malicious ZIP file attachment containing a macro-embedded Excel file that led to an Ursnif infection was used to initially compromise the victim network.

- Several actors utilized compromised credentials to access internet-facing systems via RDP. It’s unclear how the actors gained access to the credentials in these instances.

- An actor exploited a vulnerability in a client SonicWall appliance categorized as CVE-2021-20016 to gain access to credentials needed to access the environment.

- An actor utilized the Exchange CVE-2021-27065 and CVE-2021-26855 vulnerabilities to gain access to an internet-facing Exchange server, which ultimately allowed the actor to create a local administrator account named “admin” that was added to the “Remote Desktop Users” group.

How REvil Threat Actors Establish Their Presence Within an Environment

Once access is obtained, REvil threat actors typically utilize Cobalt Strike BEACON to establish their presence within an environment. In several instances we observed, they used the remote connection software ScreenConnect and AnyDesk. In other cases, they chose to create their own local and domain accounts, which they added to the “Remote Desktop Users” group. Further, the threat actors often disabled antivirus, security services and processes that would interfere with or otherwise detect their presence within the environment.

Below are specific techniques we observed thus far in 2021:

- Once the actor had access to the environment, they utilized different toolsets to establish and maintain their access, including the use of Cobalt Strike BEACON as well as local and domain account creation. In one instance, the REvil group utilized a BITS job to connect to a remote IP, download and then execute a Cobalt Strike BEACON.

- In several incidents, Unit 42 identified the use of “Total Deployment Software” by REvil threat actors to deploy ScreenConnect and AnyDesk software to maintain access within the environment.

- In many instances, the REvil actor(s) created local and domain level accounts through BEACON and NET commands even if they had access to domain-level administrative credentials.

- Unit 42 observed common evasion techniques across all engagements in which REvil threat actors used [1-3] alphanumeric batch and PowerShell scripts that stopped and disabled antivirus products, services related to Exchange, VEAAM, SQL and EDR vendors, as well as enabled terminal server connections.

How REvil Threat Actors Expand Access and Gather Intelligence

In most cases, REvil actors need to gain access to additional accounts that have a wider set of privileges in order to move further within the victim environment and carry out their mission. They often use Mimikatz to access cached credentials on the local host. However, Unit 42 also observed the SysInternals tool procdump as a means to dump the LSASS process. Unit 42 also found it common for this threat actor to access files with the name “password” within the filename. In one instance, we observed an attempt to gain access to a KeePass Password Safe.

During the reconnaissance phase of attacks, REvil threat actors often utilize various open source tools to gather intelligence on a victim environment and in some cases resort to utilizing administrative commands NETSTAT and IPCONFIG to gather information.

Below are specific observations of REvil’s behavior in 2021.

- Network reconnaissance tools netscan, Advanced Port Scanner, TCP View and KPort Scanner were observed in over half the engagements Unit 42 responded to.

- The threat actors often use Bloodhound and AdFind to map out networks and gather other active directory information.

- In two engagements, Unit 42 observed the use of ProcessHacker and PCHunter in what appeared to be an attempt to gain insight into processes and services running on hosts within the environment.

How REvil Threat Actors Move Laterally Throughout Compromised Environments

In general, REvil threat actors utilize Cobalt Strike BEACON and RDP with previously compromised credentials to laterally move throughout compromised environments. Additionally, Unit 42 observed use of the ScreenConnect and AnyDesk software as methods of lateral movement. While we have seen other ransomware groups employ these tactics, we observed REvil threat actors retrieving these binaries from file sharing sites such as MEGASync and PixelDrain.

How REvil Threat Actors Complete Their Objectives

Finally, we observed REvil threat actors moving to the final stage of their attack, encrypting networks, staging and exfiltrating data, and destroying data to prevent recovery and hinder analysis.

Ransomware Deployment

- REvil threat actors typically deployed ransomware encryptors using the legitimate administrative tool PsExec with a text file list of computer names or IP addresses of the victim network obtained during the reconnaissance phase.

- In one instance, a REvil threat actor utilized BITS jobs to retrieve the ransomware from their infrastructure. In a separate instance, the REvil threat actor hosted their malware on MEGASync.

- REvil threat actors also logged into hosts individually using domain accounts and executed the ransomware manually.

- In two instances, the REvil threat actor utilized the program dontsleep.exe in order to keep hosts on during ransomware deployment.

- REvil threat actors often encrypted the environment within seven days of the initial compromise. However, in some instances, the threat actor(s) waited up to 23 days.

Exfil

- Threat actors often used MEGASync software or navigated to the MEGASync website to exfiltrate archived data.

- In one instance, the threat actor used RCLONE to exfiltrate data.

Defense Maneuvers

During the encryption phase of these attacks, the REvil threat actors utilized batch scripts and wevtutil.exe to clear 103 different event logs. Additionally, while not an uncommon tactic these days, REvil threat actors deleted Volume Shadow Copies in an apparent attempt to further prevent recovery of forensic evidence.

Conclusion: Evolve

While the REvil operational group may target large organizations, all are potentially susceptible to attack. As we draw closer to a post COVID-19 environment, IT and other defenders of networks should take time to learn what’s normal in their environments and notice and question abnormalities. Investigate them. Question your defenses. Do all users need to be able to open macro-enabled documents? Do you have endpoint visibility and protections to, at minimum, alert you to secondary infections such as QakBot? If you absolutely need RDP, are you using tokenized MFA? And don’t question just once – question routinely. Think like the attacker. You might be able to stop your organization from being the next victim and escape being in the headlines for the wrong reasons.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected by:

- WildFire: All known samples are identified as malware.

- Cortex XDR with:

- Prevention for known REvil indicators

- Anti-Ransomware Module to prevent REvil encryption behaviors.

- Local Analysis detection to prevent REvil binary executions.

- Behavioral Threat Protection, Anti-exploitation modules and Suspicious Process Creation to prevent REvil techniques.

- XDR Analytics, Analytics BIOCs and BIOCs to detect REvil techniques.

- AutoFocus: Tracking related activity using the REvil tag.

- Cortex XSOAR: “Kaseya VSA 0-day - REvil Ransomware Supply Chain Attack” playbook. Playbook includes the following tasks:

- Collect related known IOCs from several sources.

- Indicators, PS commands, Registry changes and known HTTP requests hunting using PAN-OS, Cortex XDR and SIEM products.

- Block IOCs automatically or manually.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Additional Resources

Threat Assessment: GandCrab and REvil Ransomware

2022 Unit 42 Ransomware Threat Report Highlights: Ransomware Remains a Headliner

Ransomware Trends: Higher Ransom Demands, More Extortion Tactics

Breaking Down Ransomware Attacks

Ransomware’s New Trend: Exfiltration and Extortion

Cortex XSOAR playbook documentation

Originally posted July 6, 2021. Now updated with additional 2022 insights.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh