This post is also available i 2022-6-24 21:0:13 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:23 收藏

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Unit 42 has discovered Zloader and BazarLoader samples that had interesting implementations of a sandbox evasion technique. This blog post will go into details of the unique implementations of API Hammering in these types of malware. API Hammering involves the use of a massive number of calls to Windows APIs as a form of extended sleep to evade detection in sandbox environments.

Sandboxing is a popular technique used to detect if a sample is malicious. A sandbox analyzes the behaviors of the binary as it executes inside a controlled environment. Sandboxes have to deal with many challenges while analyzing a large number of binaries with limited computing resources. Malware sometimes abuses these challenges by “sleeping” in the sandbox before carrying out malicious procedures to hide its real intentions.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from malware families using evasion techniques through Cortex XDR or the Next-Generation Firewall with WildFire and Threat Prevention security subscriptions.

Table of Contents

Common Ways for Malware to Sleep

What Is API Hammering?

API Hammering in BazarLoader

API Hammering in Zloader

Conclusion: WildFire vs API Hammering

Indicators of Compromise

Common Ways for Malware to Sleep

The most common way for malware to sleep is to simply call the Windows API function Sleep. A sneakier way that we often see is the Ping Sleep technique where the malware constantly sends ICMP network packets to an IP address (ping) in a loop. To send and receive such useless ping messages takes a certain amount of time, thus the malware indirectly sleeps. However, all these methods are easily detected by many sandboxes.

What Is API Hammering?

API Hammering has been a known sandbox bypass technique that is sometimes used by malware authors to evade sandboxes. We’ve recently observed Zloader – a dropper for multiple types of malware – and the backdoor BazarLoader using new and unique implementations of API Hammering to remain stealthy.

API Hammering consists of a large number of garbage Windows API function calls. The execution time of these calls delays the execution of the real malicious routines of the malware. This allows the malware to indirectly sleep during the sandbox analysis process.

API Hammering in BazarLoader

An older variant of BazarLoader made use of a fixed number (1550) of printf function calls to time out malware analysis. While analyzing a newer version of BazarLoader, we found a new and more complex implementation of API Hammering.

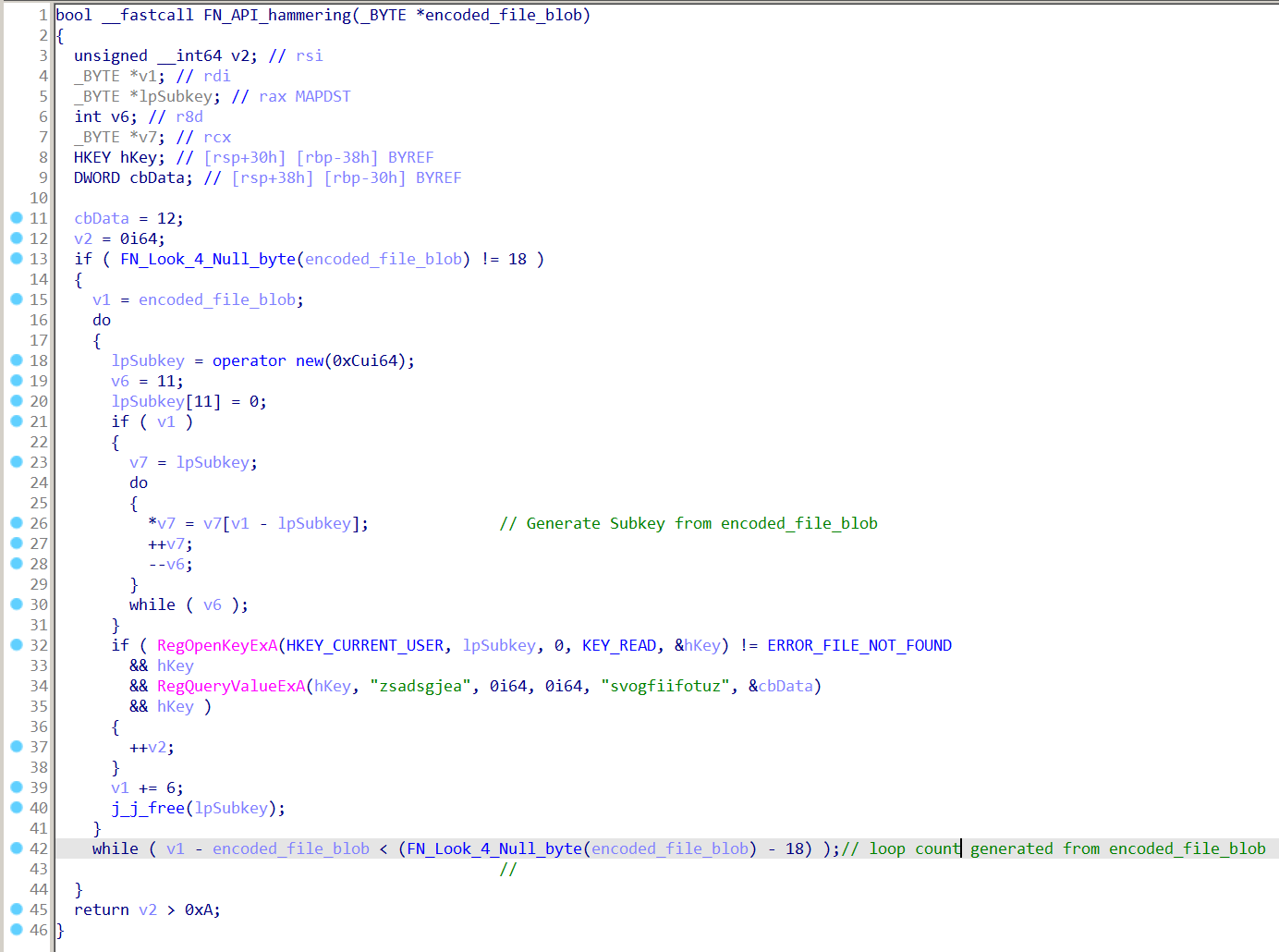

The following decompiled procedure shows how this new variant is implemented in the BazarLoader sample we analyzed. It makes use of a huge loop with a random count that repeatedly accesses a list of random registry keys in Windows.

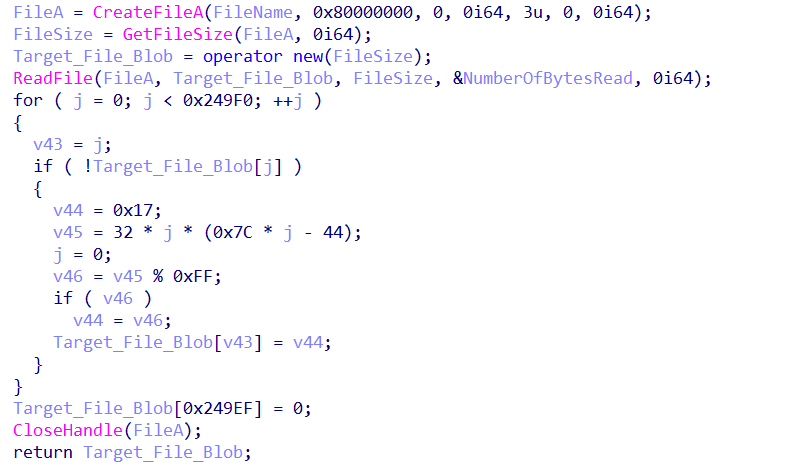

To generate the random loop count and list of registry keys, the sample reads the first file from the System32 directory that matches a defined size. This file is then encoded (see Figure 2) to remove most of its null bytes. The random count is then computed based on the offset of the first null byte in that file. The list of random registry keys are generated from fixed length chunks from the encoded file.

With a different Windows version (Windows 7, 8, etc.) and a different set of applied updates, there is also a different set of files in the System32 directory. This results in a varying loop count and list registry keys used by BazarLoader when executed in different machines.

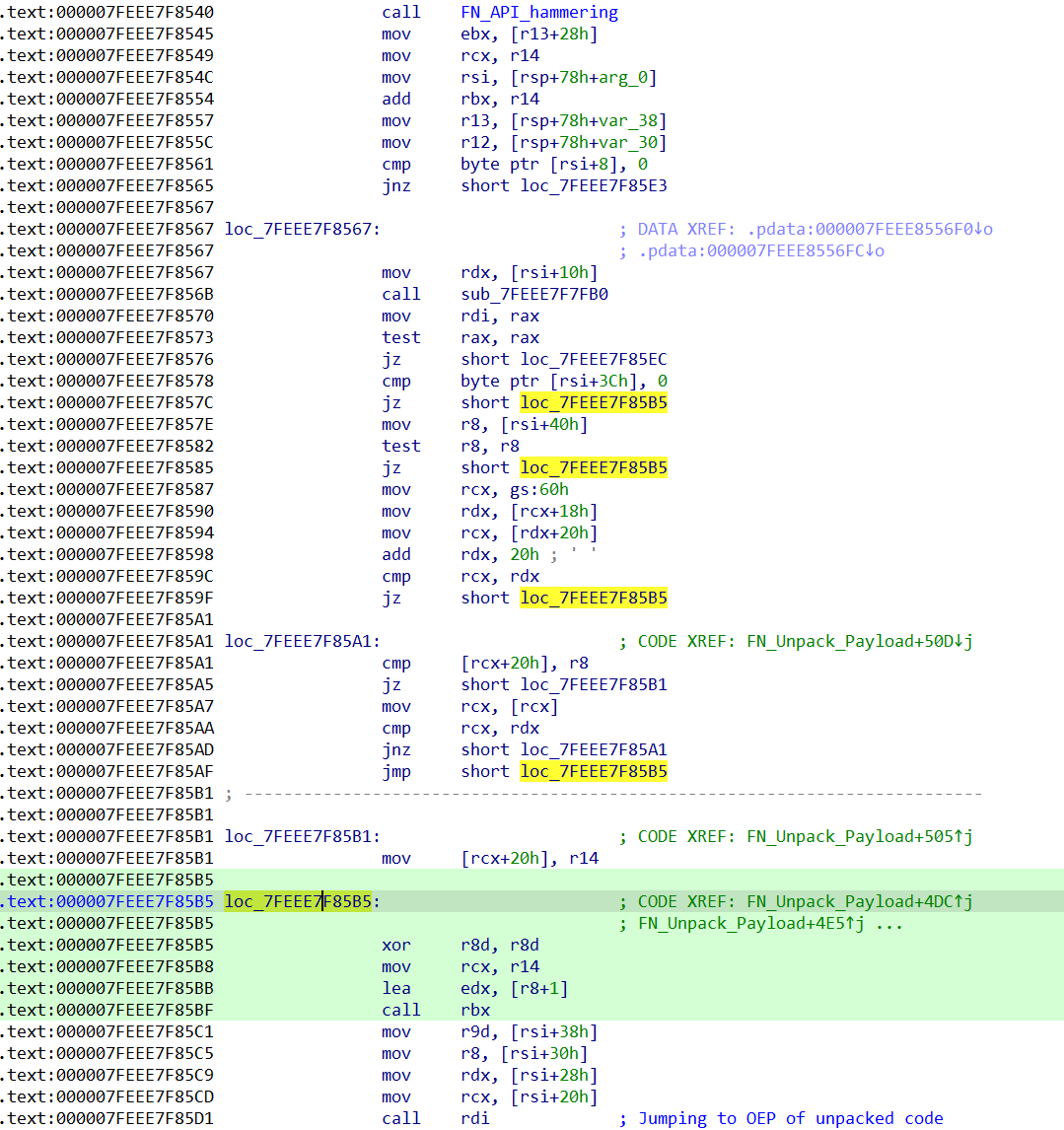

The API Hammering function is located in the packer of the BazarLoader sample (see Figure 3). It delays the payload unpacking process to evade detection of the aforementioned. Without completing the unpacking process, the BazarLoader sample would appear to be just accessing random registry keys, a behavior that can be also seen in many legitimate types of software.

API Hammering in Zloader

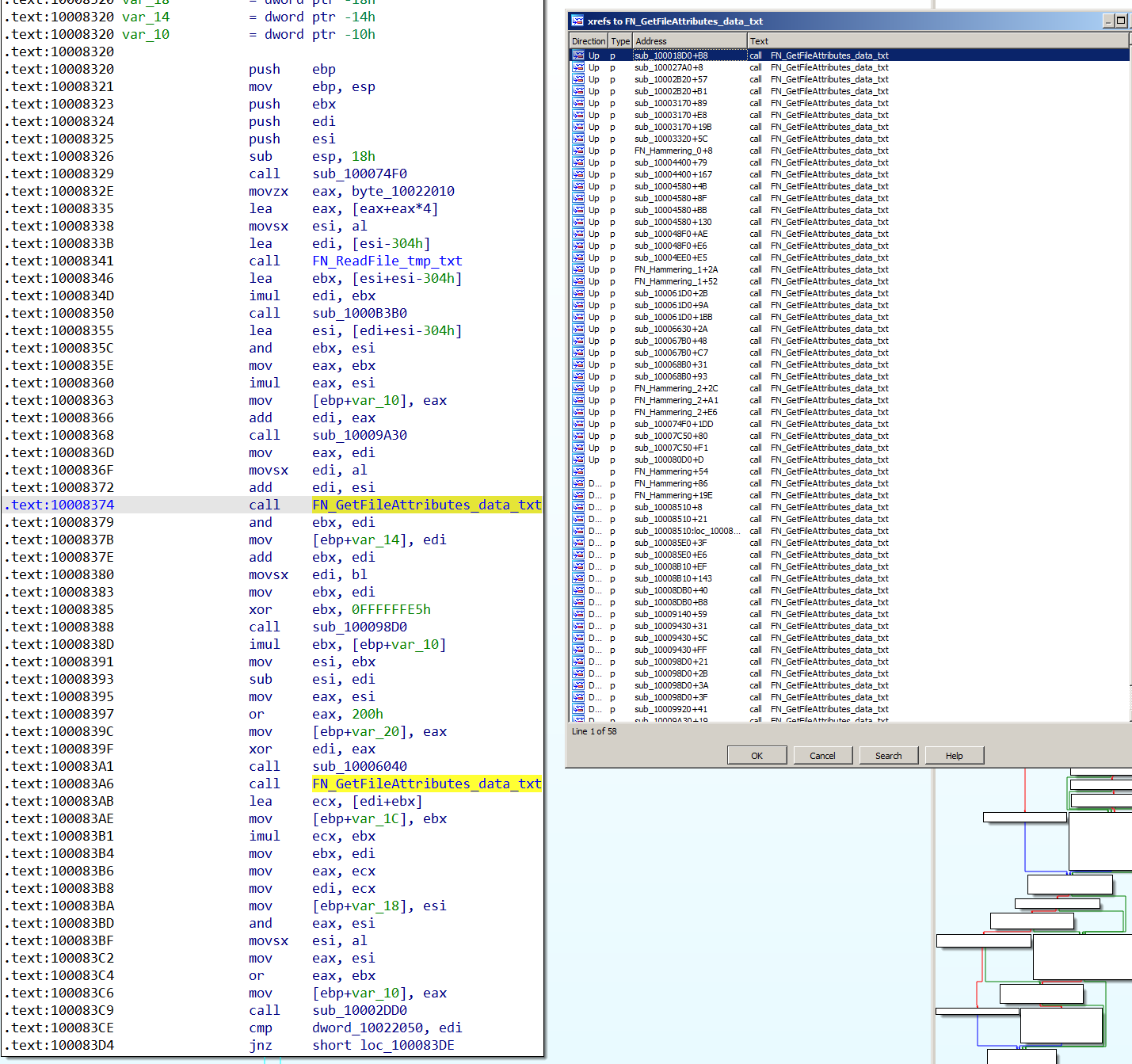

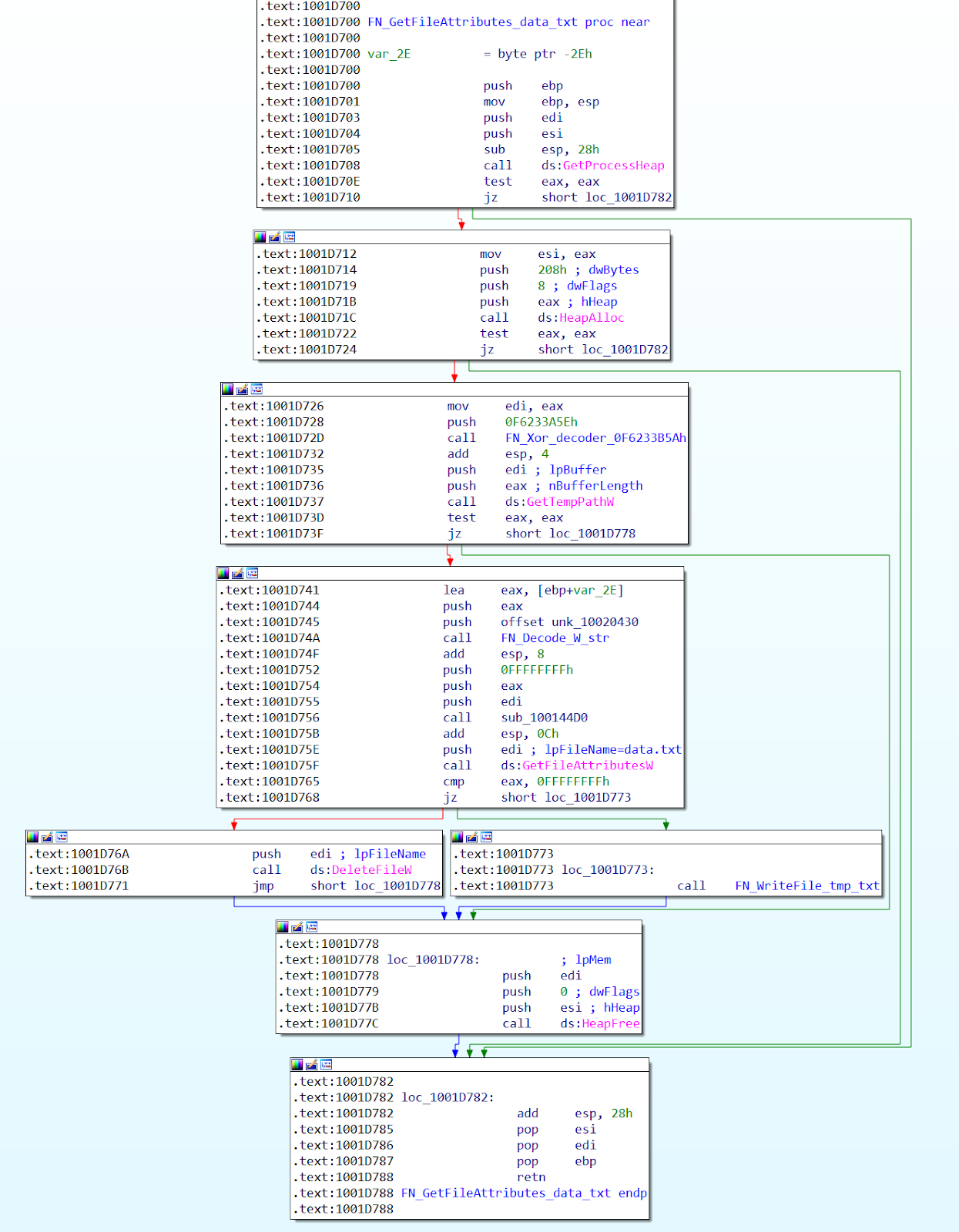

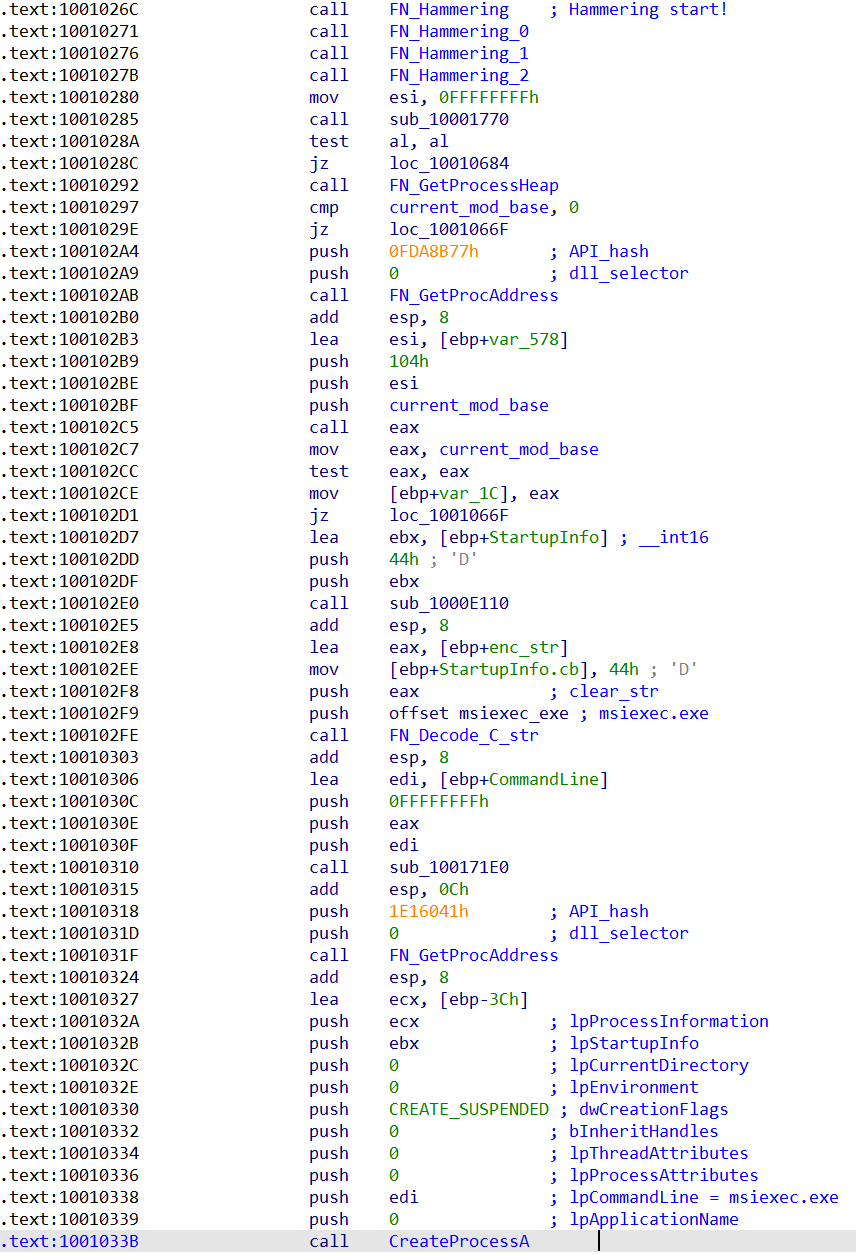

While the BazarLoader sample relied on a loop to carry out API Hammering, Zloader uses a different approach. It does not require a huge loop, but instead consists of 4 large functions which contain nested calls to multiple other smaller functions (see Figure 4).

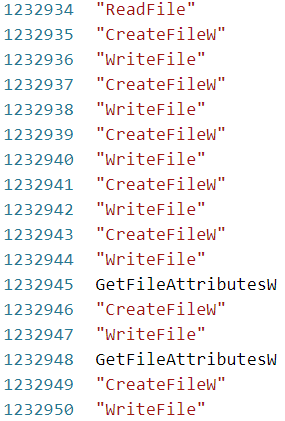

Inside each of these small procedures are four API function calls related to file I/O. The functions are GetFileAttributesW, ReadFile, CreateFileW and WriteFile (see Figure 5).

By using a debugger, we could figure out the number of calls made to four file I/O functions (see Figure 6). The large and smaller functions together generate more than a million function calls in total, without the use of a single large loop as seen in BazarLoader.

The following table shows the API function call counts made during our analysis process:

| I/O API function | Total Call Count |

| ReadFile | 278,850 |

| WriteFile | 280,921 |

| GetFileAttributesW | 113,389 |

| CreateFileW | 559,771 |

Table 1. API function call counts.

The execution time of the four large functions delays the injection of the Zloader payload. Without complete execution of these functions, the sample would appear to be a benign sample just carrying out file I/O operations.

The following disassembled code shows the four API hammering procedures followed by the injection procedures:

Conclusion: WildFire vs API Hammering

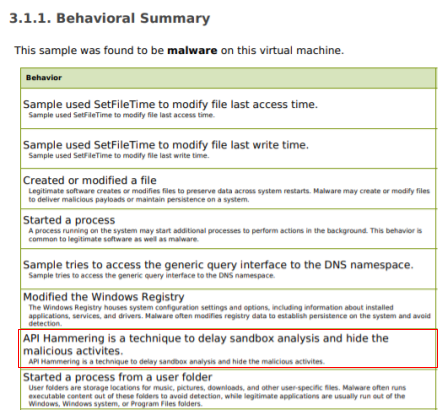

Results from analyzing various implementations of API Hammering enabled the detection of malware samples using API Hammering for sandbox evasion in WildFire. WildFire detects the use of API Hammering by BazarLoader, Zloader, and other malware families.

The following excerpt from the WildFire report of our BazarLoader sample shows the detected entry for API Hammering.

![]() Palo Alto Networks customers receive further protections against other malware families using similar sandbox evasion techniques through Cortex XDR or our Next-Generation Firewall with WildFire and Threat Prevention security subscriptions.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive further protections against other malware families using similar sandbox evasion techniques through Cortex XDR or our Next-Generation Firewall with WildFire and Threat Prevention security subscriptions.

Indicators of Compromise

BazarLoader Sample

ce5ee2fd8aa4acda24baf6221b5de66220172da0eb312705936adc5b164cc052

Zloader Sample

44ede6e1b9be1c013f13d82645f7a9cff7d92b267778f19b46aa5c1f7fa3c10b

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh