Originally published June 29, 2022 on the Fox-IT blogAuthored by Alberto Segura (main author 2022-7-6 03:58:16 Author: research.nccgroup.com(查看原文) 阅读量:37 收藏

Originally published June 29, 2022 on the Fox-IT blog

Authored by Alberto Segura (main author) and Rolf Govers (co-author)

Summary

Flubot is an Android based malware that has been distributed in the past 1.5 years in

Europe, Asia and Oceania affecting thousands of devices of mostly unsuspecting victims.

Like the majority of Android banking malware, Flubot abuses Accessibility Permissions and Services in order to steal the victim’s credentials, by detecting when the official banking application is open to show a fake web injection, a phishing website similar to the login form of the banking application. An important part of the popularity of Flubot is due to the distribution strategy used in its campaigns, since it has been using the infected devices to send text messages, luring new victims into installing the malware from a fake website. In this article we detail its development over time and recent developments regarding its disappearance, including new features and distribution campaigns.

Introduction

One of the most popular active Android banking malware families today. An “inspiration” for developers of other Android banking malware families. Of course we are talking about Flubot. Never heard of it? Let us give you a quick summary.

Flubot banking malware families are in the wild since at least the period between late 2020 and the first quarter of 2022. Most of its popularity comes from its distribution method: smishing. Threat Actors (TA) have been using the infected devices to send text messages to other phone numbers, stolen from other infected devices and stored in Command-and-Control servers (C2).

In the initial campaigns, TAs used fake Fedex, DHL and Correos – a local Spanish parcel shipping company – SMS messages. Those SMS messages were fake notifications which lured the user into a fake website in order to download a mobile application to track the shipping. These campaigns were very successful, since nowadays most people are used to buy different kinds of products online and receive that type of messages to track the shipping of the product. Flubot is not only a very active family: TAs have been very actively introducing new features, support for campaigns in new countries and improving the features it already had.

On June 1, 2022, Europol announced the takedown of Flubot in a joint operation including 11 countries. The Dutch Police played a key part in this operation and successfully disrupted the infrastructure in May 2022, rendering this strain of malware inactive. That was interesting period of time to look back at the early days of Flubot, how it evolved and became so notorious.

In this post we want to share all we know about this threat and a timeline of the most relevant and interesting (new) features and changes that Flubot’s TAs have introduced. We will focus on these features and changes related to the detected samples but also in the different campaigns that TAs have been using to distribute this malware.

The beginning: A new Android Banking Malware targeting Spain [Flubot versions 0.1-3.3]

Based on reports from other researchers, Flubot samples were first found in the wild between November and December of 2020. Public information about this malware was first published on 6 January 2021 by our partner ThreatFabric (https://twitter.com/ThreatFabric/status/1346807891152560131). Even though ThreatFabric was the first to publish public information on this new family and called it “Cabassous”, the research community has been more commonly referring to this malware as Flubot.

In the initial campaigns, Flubot was distributed using Fedex and Correos fake SMS messages. In those messages, the user was led to a fake website which was basically a “landing page” style website to download what was supposed to be an Android application to track the incoming shipping.

In this initial campaign versions prior to Flubot 3.4 were used, and TAs were including support for new campaigns in other countries using specific samples for each country. The reasons why there were different samples for different countries were:

– Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA). It was using a different seed to generate 5.000 different domains per month. Just out of curiosity: For Germany, TAs were using 1945 as seed for the DGA.

– Phone country code used to send more distribution smishing SMS messages from infected devices and block those numbers in order to avoid communication among victims.

There were no significant changes related to features in the initial versions (from 0.1 to 3.3). TAs were mostly focused on the distribution campaigns, trying to infect as many devices as possible.

There is one important change in the initial versions, but it is difficult to find the exact version in which this change was first introduced because there are some version without samples on public repositories. TAs introduced web injections to steal credentials, the most popular tactic to steal credentials on Android devices. This was introduced starting between versions 0.1 and 0.5, in December 2020.

In those initial versions, TAs increased the version number of the malware in just a few days without adding significant changes. Most of the samples – particularly previous to 2.1 – were not uploaded to public malware repositories, making it even harder to track the first versions of Flubot.

On these initial versions (after 0.5), TAs also introduced other not so popular features like the “USSD” one which was used to call to special numbers to earn money (“RUN_USSD” command), it was introduced at some point between versions 1.2 and 1.7. In fact, it seems this feature wasn’t really used by Flubot’s TAs. Most used features were the web injections to steal banking and cryptocurrency platform credentials and sending SMS features to distribute and infect new devices.

From version 2.1 to 2.8 we observed TAs started to use a different packer for the actual Flubot’s payload. It could explain why we weren’t able to find samples on public repositories between 2.1 and 2.8, probably there were some “internal” versions

used to try different packers and/or make it work with the new one.

March 2021: New countries and improvements on distribution campaigns [Flubot versions 3.4-3.7]

In fact, we can see a new version (3.6) customized for targeting victims in Germany in March 18, 2021. Only five days later, another version was released (3.7), with interesting changes. TAs were trying to use the same sample for campaigns in Spain and Germany, including Spanish and German phone country codes split by newline character to block the phone number to which the infected device is sending smishing messages.

At the same time, TAs introduced a new campaign on Hungary. By the end of March, TAs introduced a new change on version 3.7: an important change in their DGA, since they replaced “.com” TLD with “.su”. This change was important for tracking Flubot, since now TAs could use this new TLD to register new C2’s domains.

April 2021: DoH and unique samples for all campaigns [Flubot versions 3.9-4.0]

which domains were being resolved.

In the following images we show decompiled code of this new version, including the new DoH code. TAs kept the old classic DNS resolving code. TAs introduced code to randomly choose if DoH or classic DNS should be used.

The introduction of DoH was not the only feature that was added to Flubot 3.9. TAs also added some UI messages to prepare future campaigns targeting Italy.

Those messages were used a few days later in the new Flubot 4.0 version, in which TAs finally started to use one single sample for all of the campaigns – no more unique samples to targeted different countries.

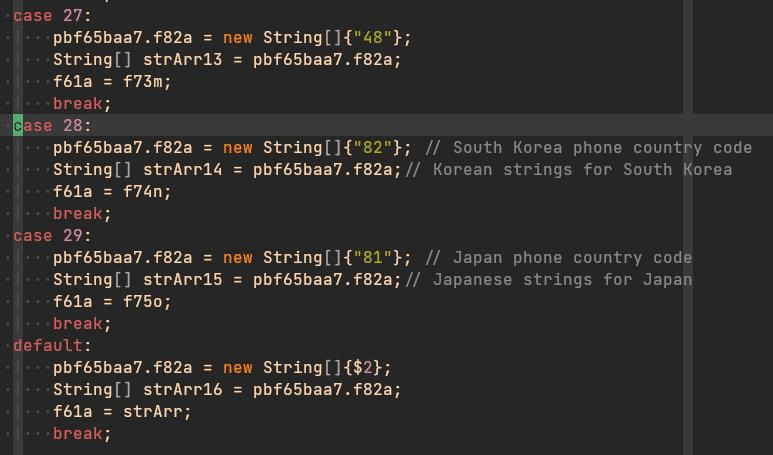

With this new version, the targeted country’s parameters used on previous version of Flubot were chosen depending on the victim’s device language. This way, if the device language was Spanish, then Spanish parameters were used. The following parameters were chosen:

– DGA seed

– Phone country codes used for smishing and phone number blocking

May 2021: Time for infrastructure and C2 server improvements [Flubot versions 4.1-4.3]

In this new version, TAs have changed one more time the DoH servers used to resolve the C2 domains. In this case, they introduced three different services or DNS servers: Google, CloudFlare and AliDNS. The last one was used for the first time in the life of Flubot to resolve the DGA domains.

Those three different DoH services or servers were chosen randomly to resolve the generated domains, to finally make the requests to any of the active C2 servers.

These changes also brought a new campaign in Belgium, in which TAs used fake BPost app and smishing messages to lure new victims. One week later, new campaigns in Turkey were also introduced, this time in a new Flubot version with important changes related to its C2 protocol.

The first samples of Flubot 4.2 appeared on 17 May 2021 with a few important changes in the code used to communicate with the C2 servers. In this version, the malware was sending HTTP requests with a new path in the C2: “p.php”, instead of the classic “poll.php” path.

At first sight it seemed like a minor change, but paying attention to the code we realized there was an important reason behind this change: TAs changed the encryption method used for the protocol to communicate with the C2 servers.

Previous versions of Flubot were using simple XOR encryption to encrypt the information exchanged with the C2 servers, but this new version 4.2 was using

RC4 encryption to encrypt that information instead of the classic XOR. This way, the C2 server still supported old versions and new version at the same time:

- poll.php and poll2.php were used to send/receive requests using the old XOR encryption

- p.php was used to send and receive requests using the new RC4 encryption

Besides the new protocol encryption on version 4.2, TAs also added at the end of May support for new campaigns in Romania.

Finally, on 28 May 2021 new samples of Flubot 4.3 were discovered with minor changes, mainly focused on the strings obfuscation implemented by the malware.

June 2021: VoiceMail. New campaign new countries [Flubot versions 4.4-4.6]

One more time, no major changes in this new version. TAs added support for campaigns in Portugal. As we can see with versions 4.3 and 4.4, it was common for Flubot’s TAs to bump the version number in just a few days, with just minor changes. Some versions were not even found in public repositories (e.g. version 3.3), which suggests that some versions were never used in public or just skipped and TAs just bumped the version. Maybe those “lost versions” lasted just a few hours in the distribution servers and were quickly updated to fix bugs.

In the month of June the TAs hardly made any changes related to features, but instead they were working on new distribution campaigns.

On version 4.5, TAs added Slovakia, Czech Republic, Greece and Bulgaria to the list of supported countries for future campaigns. TAs reused the same DGA seed for all of them, so it didn’t require too much work from their part to get this version released.

A few days after version 4.5 was observed, a new version 4.6 was discovered with new countries added for future campaigns: Austria and Switzerland. Also, some countries that were removed in previous versions were reintroduced: Sweden, Poland, Hungary, and The Netherlands.

This new version of Flubot didn’t come only with more country coverage. TAs introduced a new distribution campaign lure: VoiceMail. In this new “VoiceMail” campaign, infected devices were used to send text messages to new potential victims using messages in which the user was lead to a fake website. This time a “VoiceMail” app was installed, which should allow the user to listen to the received Voice mail messages. In the following image we can see the VoiceMail campaign for Spanish users.

July 2021: TAs Holidays [Flubot versions 4.7]

Besides the changes related to the DGA seeds, TAs also introduced support for campaigns in new countries: Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There was almost no Flubot activity in summer. Our assumption is the developers were busy with their summer holidays. As we will see in the following section, TAs will recover their activity in August and October.

August-September 2021: Slow come back from Holidays [Flubot versions 4.7-4.9]

One more version bump for Flubot was discovered on September, when version 4.9 came out with some more minor changes, just like the previous version 4.8. This time, new web injections were introduced in the C2 servers to steal credentials from victims. Those two new versions with minor changes (not very relevant) seems like a relaxed come back to activity. From our point of view, the most interesting thing that happened in those two months is that TAs started to distribute another malware family using the Flubot botnet. We received from C2 servers a few smishing tasks in which the fake “VoiceMail” website was serving Teabot (also known as Anatsa and Toddler) instead of Flubot.

That was very interesting because it showed that Flubot’s TAs could be also associated with this malware family or at least could be interested on selling the botnet for smishing purposes to other malware developers. As we will see, that was not the only family distributed by Flubot.

October-November 2021: ‘Android Security Update’ campaign and new big protocol changes [Flubot versions 4.9]

At the beginning of October, we saw a campaign different from the previous DHL / Correos / Fedex campaigns or the “VoiceMail” campaign. This time, TAs started to distribute Flubot as a fake security update for Android. It seems this new distribution campaign wasn’t working as expected, since TAs kept using the “VoiceMail” distribution campaign after a few days.

TAs were very quiet until late November, when they finally released new samples with important changes in the protocol used to communicate with C2 servers. After bumping the version numbers so quickly at the beginning, now TAs weren’t bumping the version number

even with a major change like this one.

This protocol change allowed the malware to communicate with the C2 servers without starting a direct connection with them. Flubot used TXT DNS requests to common public DNS servers (Google, CloudFlare and AliDNS). Then, those requests were forwarded to the actual C2 servers (which implemented DNS servers) to get the TXT record response from the servers and forward it to the malware. The stolen information from the infected device was sent encrypting it using RC4 (in a very similar way to the used in the previous protocol version) and encoding the encrypted bytes. This way, the encoded payload was used as a subdomain of the DGA generated domain. The response from C2 servers was also encrypted and encoded as the TXT record response to the TXT request, and it included the commands to execute smishing tasks for distribution campaign or the web injections used to steal credentials.

With this new protocol, Flubot was using DoH servers from well known companies such as Google and CloudFlare to establish a tunnel of sorts with the C2 servers. With this technique, detecting the malware via network traffic monitoring was very difficult, since the malware wasn’t establishing connections with unknown or malicious servers directly. Also, since it was using DoH, all the DNS requests were encrypted, so network traffic monitoring couldn’t identify those malicious DNS requests.

This major change in the protocol with the C2 servers could also explain the low activity in the previous months. Possibly developers were working on ways to improve the protocol as well as the code of both malware and C2 servers backend.

December 2021: ‘Flash Player’ campaign and DGA changes [Flubot versions 5.0-5.1]

No more new versions or changes were observed until the end of December, when the TAs wanted to say goodbye to the 2021 by releasing Flubot 5.1. The first samples of Flubot 5.1 were detected on December 31. As we will see in the following section, on January 2 Flubot 5.2 samples came out. Version 5.1 came out with some important changes on DGA. This time, TAs introduced a big list of TLDs to generate new domains, while they also introduced a new command used to receive a new DGA seed from the C2 servers – UPDATE_ALT_SEED. Based on our research, this new command was never used, since all the newly infected devices had to connect to the C2 servers using the domains generated with the hard-coded seeds.

Besides the new changes and features added in December, TAs also introduced a new campaign: “Flash Player”. This campaign was used alongside with “VoiceMail” campaign, which still was the most used to distribute Flubot. In this new campaign, a text message was sent to the victims from infected devices trying to make them install a “Flash Player” application in order to watch a fake video in which the victim appeared. The following image shows how simple the distribution website was, shown when the victim opens the link.

January 2022: Improvements in Smishing features and new ‘Direct Reply’ features [Flubot versions 5.2-5.4]

A few days after new sample of version 5.2 was discovered, samples of version 5.3 were detected. In this case, no new features were introduced. TAs removed some unused old code. This version seemed like a version used to clean the code. Also, three days after the first samples of Flubot 5.3 appeared, new samples of this version were detected with support for campaigns in new countries: Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Thailand.

By the end of January, TAs released a new version: Flubot 5.4. This new version introduced a new and interesting feature: Direct Reply. The malware was now capable to intercept the notifications received in the infected device and automatically reply them with a configured message received from the C2 servers.

To get the message that would be used to reply notifications, Flubot 5.4 introduces a new request command called “GET_NOTIF_MSG”. As the following image shows, this request command is used to get the message to finally be used when a new notification is received.

Even though this was an interesting new feature to improve the botnet’s distribution power, it didn’t last too long. It was removed in the following version.

In the same month we detected Medusa, another Android banking malware, distributed in some Flubot smishing tasks. This means that, one more time, Flubot botnet was being used as a distribution botnet for distribution of another malware family. In August 2021 it was used to distribute Teabot. Now, it has been used to distribute Medusa.

If we try to connect the dots, it could explain the new “Direct Reply” feature and the usage of “multipart messages”. Those improvements could have been introduced due to suggestions made by Medusa’s TAs in order to use Flubot botnet as distribution service.

February-March-April 2022: New cookie stealing features [Flubot versions 5.5]

The first thing we realized by looking at the new code was a little change when requesting the list of targeted apps. This request must include the list of installed applications in the infected device. As a result, the C2 server would provide the subset of apps which are targeted. In this new version, “.new” was appended to the package names of installed apps when doing the “GET_INJECTS_LIST” request.

At the beginning, the C2 servers were responding with URLs to fetch the web injections for credentials stealing when using “.new” appended to the package’s name. After some time, C2 servers started to respond with the official URL of the banks and crypto-currency platforms, which seemed strange. After analysis of the code, we realized they also introduced code to steal the cookies from the WebView used to show web injections – in this case, the targeted entity’s website. Clicks and text changes in the different UI elements of the website were also logged and sent to the C2 server, so TAs were not only stealing cookies: they were also able to steal credentials via “keylogging”.

The cookies stealing code could receive an URL, the same way it could receive a URL to fetch web injections, but this time visiting the URL it wasn’t receiving the web injection. Instead, it was receiving a new URL (the official bank or service URL) to be loaded and to steal the credentials from. In the following image, the response from a compromised website used to download the web injections is shown. In this case, it was used to get the payload for stealing GMail’s cookies (shown when the victim tries to open Android Email application).

After the victim logs in to the legitimate website, Flubot will receive and handle an event when the website ends loading. At this time, it gets the cookies and sends them to the C2 server, as can be seen in the following image.

May 2022: MMS smishing and.. The End? [Flubot versions 5.6]

Once again, after one month without new versions in the wild, a new version of Flubot came out at the beginning of May: Flubot 5.6. This is the last known Flubot version.

This new version came with a new interesting feature: MMS smishing tasks. With this new feature, TAs were trying to bypass carriers detections, which were probably put in place after more than a year of activity. A lot of users were infected and their devices where sending text messages without their knowledge.

To introduce this new feature, TAs added new request’s commands:

– GET_MMS: used to get the phone number and the text message to send (similar to the usual GET_SMS used before for smishing)

– MMS_RATE: used to get the time rate to make “GET_MMS” request and send the message (similar to the usual SMS_RATE used before for smishing).

After this version got released on May 1st, the C2 servers stopped working on May 21st. They were offline until May 25th, but they were still not working properly, since they were replying with empty responses. Finally, on June 1st, Europol published on their website that they took down the Flubot’s infrastructure with the cooperation of police from different countries. Dutch Police was the one that took down the infrastructure. It probably happened because Flubot C2 servers, at some point in 2022, changed the hosting services to a hosting service in The Netherlands, making it easier to take down.

Does it mean this is the end of Flubot? Well, we can’t know for sure, but it seems police wasn’t able to get the RSA private keys since they didn’t make the C2 servers send commands to detect and remove the malware from the devices.

This means that the TAs should be able to bring Flubot back by just registering new domains and setting up all the infrastructure in a “safer” country and hosting service. TAs could recover their botnet, with less infected devices due to the offline time, but still with some devices to continue sending smishing messages to infect new devices. It depends on the TAs intentions, since it seems that the police hasn’t found them yet.

Conclusion

Flubot has been one of the most – if not the most – active banking malware family of the last few years. Probably this was due to their powerful distribution strategy: smishing. This malware has been using the infected devices to send text messages to the phone numbers which were stolen from the victims smartphones. But this, in combination with fake parcel shipping messages in a period of time in which everybody is used to buy things online has made it an important threat.

As we have seen in this post, TAs have introduced new features very frequently, which made Flubot even more dangerous and contagious. A significant part of the updates and new features have been introduced to improve the distribution capabilities of the malware in different countries, while others have been introduced to improve the credentials and information stealing capabilities.

Some updates delivered major changes in the protocol, making it more difficult to detect via network monitoring, with a DoH tunnel-based protocol which is really uncommon in the world of Android Malware. It seems that TAs have even been interested on selling some kind of “smishing distribution” service to other TAs, as we have seen with the association with Teabot and Medusa.

After one year and a half, Dutch Police was able to take down the C2 servers after TAs started using a Dutch hosting service. It seems to be the end of Flubot, at least for now.

TAs still can move the infrastructure back to a “safer” hosting and register new DGA domains to recover their botnet. It’s too soon to determine that was the end of Flubot. Time will tell what will happen with this Android malware family, which has been one of the most important and interesting malware families in the last few years.

List of samples by version

0.1 – 5e0311fb1d8dda6b5da28fa3348f108ffa403f3a3cf5a28fc38b12f3cab680a0

0.5 – d3af7d46d491ae625f66451258def5548ee2232d116f77757434dd41f28bac69

1.2 – c322a23ff73d843a725174ad064c53c6d053b6788c8f441bbd42033f8bb9290c

1.7 – 75c2d4abecf1cc95ca8aeb820e65da7a286c8ed9423630498a95137d875dfd28

1.9 – 9420060391323c49217ce5d40c23d3b6de08e277bcf7980afd1ee3ce17733da2

2.1 – 13013d2f96c10b83d79c5b4ecb433e09dbb4f429f6d868d448a257175802f0e9

2.2 – 318e4d4421ce1470da7a23ece3db5e6e4fe9532e07751fc20b1e35d7d7a88ec7

2.8 – f3257b1f0b2ed1d67dfa1e364c4adc488b026ca61c9d9e0530510d73bd1cf77e

3.1 – affaf5f9ba5ea974c605f09a0dd7776d549e5fec2f946057000abe9aae1b3ce1

3.2 – 865aaf13902b312a18abc035f876ad3dfedce5750dba1f2cc72aabd68d6d1c8f

3.4 – ca18a3331632440e9b86ea06513923b48c3d96bc083310229b8c5a0b96e03421

3.5 – 43a2052b87100cf04e67c3c8c400fa203e0e8f08381929c935cff2d1f80f0729

3.6 – fd5f7648d03eec06c447c1c562486df10520b93ad7c9b82fb02bd24b6e1ec98a

3.7 – 1adba4f7a2c9379a653897486e52123d7c83807e0e7e987935441a19eac4ce2c

3.9 – 1cf5c409811bafdc4055435a4a36a6927d0ae0370d5197fcd951b6f347a14326

4.0 – 8e2bd71e4783c80a523317afb02d26cac808179c57834c5c599d976755b1dabd

4.1 – ec3c35f17e539fe617ca2e73da4a51dc8efedda94fd1f8b50a5b77d63e58ba5c

4.2 – 368cebac47e36c81fb2f1d8292c6c89ccb10e3203c5927673ce05ba29562f19c

4.3 – dab4ce5fbb1721f24bbb9909bb59dcc33432ccf259ee2d3a1285f47af478416d

4.4 – 6a03efa4ffa38032edfb5b604672e8c9e01a324f8857b5848e8160593dfb325e

4.5 – f899993c6109753d734b4faaf78630dc95de7ea3db78efa878da7fbfc4aee7cd

4.6 – ffaebdbc8c2ecd63f9b97781bb16edc62b2e91b5c69e56e675f6fbba2d792924

4.7 – a0dd408a893f4bc175f442b9050d2c328a46ff72963e007266d10d26a204f5af

4.8 – a0181864eed9294cac0d278fa0eadabe68b3adb333eeb2e26cc082836f82489d

4.9 – 831334e1e49ec7a25375562688543ee75b2b3cc7352afc019856342def52476b

4.9 – 8c9d7345935d46c1602936934b600bb55fa6127cbdefd343ad5ebf03114dbe45 (DoH tunnel protocol)

5.0 – 08d8dd235769dc19fb062299d749e4a91b19ef5ec532b3ce5d2d3edcc7667799

5.1 – ff2d59e8a0f9999738c83925548817634f8ac49ec8febb20cfd9e4ce0bf8a1e3

5.2 – 4859ab9cd5efbe0d4f63799126110d744a42eff057fa22ff1bd11cb59b49608c

5.3 – e9ff37663a8c6b4cf824fa65a018c739a0a640a2b394954a25686927f69a0dd4

5.4 – df98a8b9f15f4c70505d7c8e0c74b12ea708c084fbbffd5c38424481ae37976f

5.5 – 78d6dc4d6388e1a92a5543b80c038ac66430c7cab3b877eeb0a834bce5cb7c25

5.6 – 16427dc764ddd03c890ccafa61121597ef663cba3e3a58fc6904daf644467a7c

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh