I accidentally ended up learning a lot about the Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823. It’s a fasci 2022-6-13 03:0:0 Author: www.tbray.org(查看原文) 阅读量:30 收藏

I accidentally ended up learning a lot about the Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823. It’s a fascinating set of stories, worth sharing, worth learning about.

Accidentally? · I’d always liked the name “Demerara” partly because my Dad loved molasses (on pancakes, toast, whatever) and so my childhood memories are rich with images of a big sticky black pot of Demerara Molasses on the breakfast table. I’ve recently released a software project I’ve been working on for a few months and thought I’d use that name. But I did a web search for “demerara” and thus discovered the 1823 Rebellion (shame on me for not having known about it). Anyhow, I quickly ran across multiple statements that the Rebellion’s leader was Quamina, and loved that name so much that I stole it for my project. Here it is on this blog and on GitHub.

Apologies and triggers · I regard myself as reasonably historically literate but somehow had never learned much about slavery: Its culture or economics or the experience of the enslaved. Again, shame on me.

Now, trigger warnings, and I mean all of them: This story is full of appalling racism and sexual abuse and sordid death and sickening hypocrisy. Blecch.

The sources · There’s been less published on this than you might think. I recommend starting, as I did, with Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara by Joshua Bryant, who was an accountant in Georgetown, the colony capital, and a member of the militia that battled the rebels. The link above is to the Internet Archive, where you can read this for free. It was published the year after the rebellion and is thus very fresh. It’s much more fair than one might expect. Pretty well just the facts and, while the whole thing is implicitly totally racist, I have trouble recollecting anything explicitly racist or mean-spirited from Bryant.

The typography is terrible and the whole book devolves into a series of footnotes that drive the supposed main text into a pathetic couple of lines across the top of the page. But the story is strong and the images are cool.

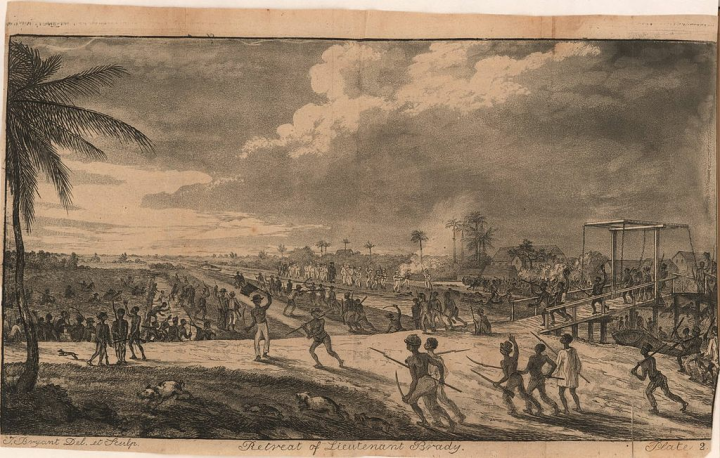

“Retreat of Lt Brady” from Bryant’s Account.

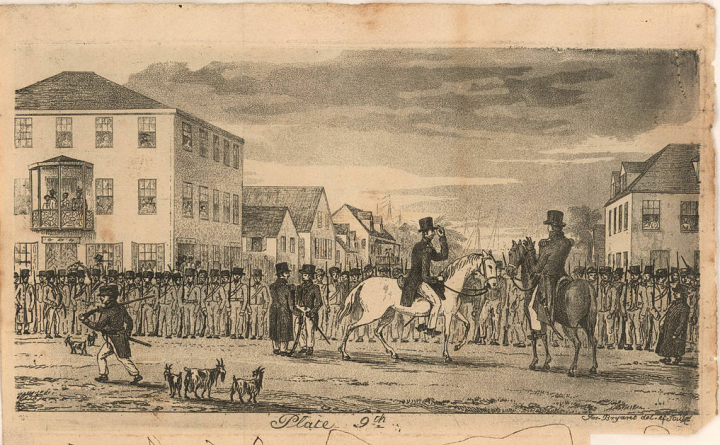

“Pate 9” (Marine Battalion at Cummingsburgh) from Bryant’s Account. Bryant was a member of this Battalion.

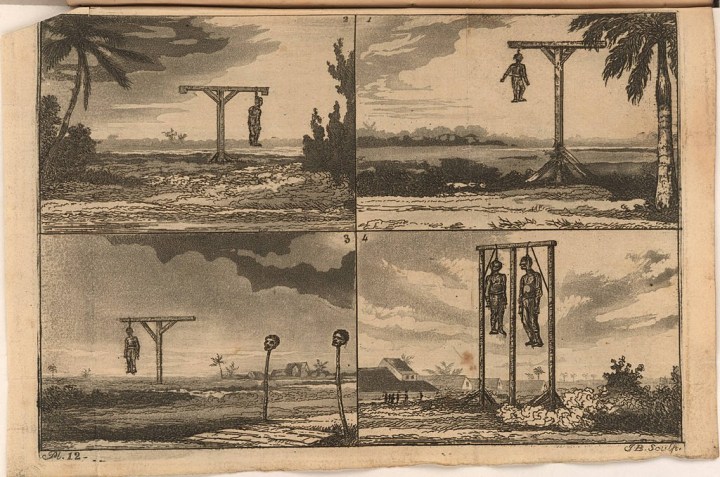

“The Gallows; Five of the culprits in chains, as they appeared on the 20th of September, 1823”. From Bryant’s Account.

The second book is Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823 by Emília Viotti da Costa, published in 1994. It’s a serious modern work of history, competently if not beautifully written, impeccably sourced, usefully illustrated. I may read more on the Rebellion but, after Bryant and da Costa, I don’t feel I really need to to get the picture.

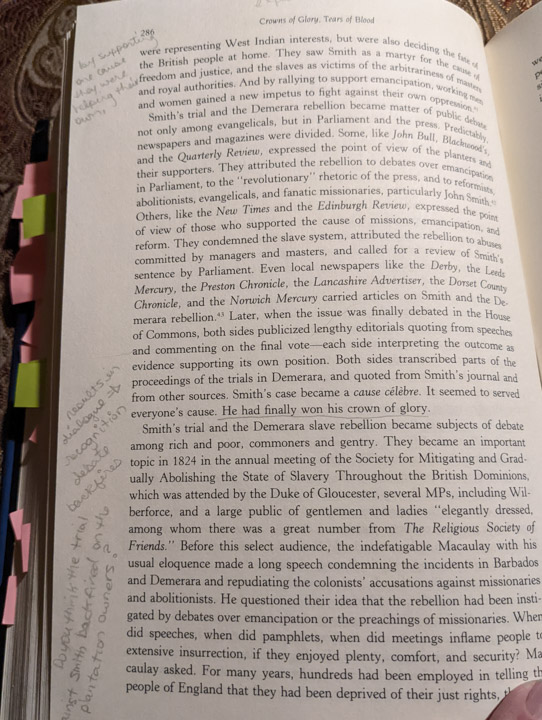

Below is a picture of a page from da Costa’s book, which I borrowed from the public library. More people should take books out of libraries. You should too.

For books that I want to take notes on and write about, I’ve become very accustomed to Kindle, which makes this easy. But I was sitting up late working on this one with the help of sticky notes and enjoying the penciled annotations of a previous reader whose identity I’ll never know, and thinking “maybe there’s something to this physical-book idea.”

The story · Demerara produced cotton, coffee, and sugar on plantations which were long and narrow, one of the narrow ends up against the sea or a huge river. The work was labor-intensive, and the labor was slave labor. The slaves were hideously oppressed. Some of the English and Dutch owners were onsite but many were absentees, represented by a local slave-driver (the first occasion I’ve ever had to use that term literally).

Around 1800 the London Missionary Society started a well-organized and well-funded effort to bring Christianity to the slaves; teach them to read, to know Scripture, and to join the church. Many of the slaves took to this eagerly and the congregations were large. The plantation-owner class hated the missionaries, resisted their arrival, and tried in every way to undermine and circumscribe them. They believed (correctly) that slaves who could read, and who regarded their souls as the equals of free people’s, would be less tractable.

The slave trade was outlawed in 1808 (not slavery, just the extraction of human flesh and blood from Africa). This, and the missionary outreach, were part of a growing anti-slavery movement in Britain, led by Wilberforce.

The movement had not been successful in outlawing slavery, but in 1823 they managed to get an Order In Council which forbade the flogging of female slaves and limited working hours to nine per day.

The colonial administration and the planters hated this and dragged their feet on implementing or even announcing it. But word got out among the slaves, many of whom came to believe they had been given their freedom by the King and that the local administration was keeping it from them.

The revolt broke out on the 18th of August, 1823, and was joined by over ten thousand slaves. The level of violence was low; few of the white planters and administrators were killed or even injured. The Governor declared martial law, supplemented his existing military forces by conscripting basically every white male, and sent them out to fight, well-armed and reasonably well-organized.

It was all over in less than a week. Many of the slaves who were perceived as leaders were unceremoniously hanged on the spot, and then there was a series of ludicrously unfair show trials at which basically every slave brought forth was briskly condemned to death. The executions were public and conducted with high ceremony, as a propaganda exercise.

While the Rebellion failed, it may have changed the course of history. But before I come back to that, let’s meet the people involved.

Dramatis personae · The central figure is Jack Gladstone, the slave who actually led the rebellion. He was Quamina’s son, born a slave. As a cooper, a skilled worker, he had considerable scope for travel among the plantations. He was tall and charismatic and passionate, convinced that the slave-masters were withholding the King’s freedom. I’m going to call him just Jack because “Gladstone” was the name of the absentee plantation owner, which slaves inherited by default.

He lost his wife Susanna when she was taken as mistress by a white plantation manager.

Jack was captured a few days into the rebellion and, weeks later, given an unusually extended and ceremonious trial with, unlike the other slaves, assistance from an attorney. Many witnesses, both colonialists and slaves, were called. Bryant’s book includes a lot of material from this trial. The testimony made it clear that once the Rebellion was ablaze, Jack had taken the lead on multiple occasions in protecting the whites from slaves that had extremely well-founded motivations for inflicting extreme violence on them.

Nonetheless, he was sentenced to hang. Not wanting to create a martyr, the colonial Governor applied to the King for mercy for Jack and a few other convicted slaves, on the grounds of his protection of the whites. The mercy was granted, Jack was sold to another slave-owner in Santa Lucia, sent there, and vanishes from history.

John Wray was one of the first missionaries in Demerara, arriving in January 1809. He was doggedly determined in the face of the planters’ resistance, and got considerable support from the administration back in Britain. Eventually he was successful in reaching out to the slaves and built large and thriving congregations across multiple plantations.

His message was not revolutionary, and heavily emphasized the “Christian duty” of obedience and loyalty to the masters. Whatever he said, the message of the equality of souls was implicit in the Scripture the slaves had learned to read, and they apparently drew their own highly reasonable conclusions about justice and morality. Furthermore, Wray himself treated the slaves with respect as humans, and several of them took up roles as church deacons and catechism instructors. He was proactive in trying to mediate disputes between slaves and masters.

He also preached Christian sexual morality, which was being violently contravened every day by the plantation owners, who flagrantly feasted sexually on the infinitely-vulnerable Black women they owned. Once again, the slaves could and did draw the obvious conclusion.

Finally, he fiercely defended the Sabbath, and the right of slaves to attend Sunday service. This was another irritant to the slave-owners, who felt entitled to seven days of work from humans they saw as property.

In 1816, under pressure from the colonists and following on the death of the pious plantation owner who had supported his arrival and residence, John Wray accepted another position in a nearby colony.

His replacement John Smith arrived in early 1817. Smith took up where Wray left off, enlarging still further the slaves’ enthusiasm for and their practice of religion. He is a truly interesting character; a poor simple Englishman who perhaps joined the Missionary cause mostly in search of a living, a man who became possessed by his mission, a man who was a living lesson that Black slaves could and should be treated like humans, a man who became (in private) revolted at the existence of slavery.

Smith may have known that the Rebellion was about to break out, but was apparently consistent in advising the slaves against it. On the other hand, he angrily refused to join the white militia that was putting the Rebellion down.

Finally, Quamina. He was born in West Africa and kidnapped away to Demerara with his mother while very young. He was a skilled worker, a carpenter. An early and enthusiastic adopter of Wray’s missionary message, he became literate, was baptized in 1808, and was elected Deacon in Wray’s church. Later, he worked closely with John Smith and his wife. Both Wray and Smith regarded him highly, praising him in their diaries

Statue of Quamina in Georgetown, Guyana. It’s unlikely the artist had any reliable sources for what he looked like, but the cross and the cutlass capture an important part of the message.

When Quamina’s long-time partner Peggy became ill, his slavemaster refused him time off to care for her; one day after work he found her dead.

Quamina must have known about the planned rebellion. But when it broke out, he strongly advised the slaves to wait, wait for the King’s freedom to be proclaimed. They didn’t.

We don’t know if he participated in the Rebellion, although the colonial government repeatedly proclaimed he was the ringleader. We do know that he swore he would never be taken alive by the whites, and that on September 16, he was tracked down by a colonial military party, ignored their orders to stop, and was shot dead.

The aftermath · Jack Gladstone’s trial was not the main legal event. John Smith was arrested and charged with having promoted “discontent and dissatisfaction, in the minds of the negro slaves toward their lawful masters, managers, and overseers” and various other charges. He was brought to trial before a court martial in October 1823.

Smith represented himself and consciously turned the trial into a piece of political theater. It’s a hell of a story, nicely told by da Costa.

The court martial found Smith guilty and issued the usual death sentence, but an appeal for mercy was sent to the King across the sea. Mercy was granted, but Smith died of consumption in prison before the mercy arrived.

Which led to a huge scandal back in Britain, where Smith was presented as a saint martyred by the cruel, grasping plantation owners. The narrative had the advantage of being pretty well the truth.

While you can argue about details and might-have-beens, historians seem to feel that that the white-hot scandal around the trial significantly advanced the anti-slavery cause, leading inexorably to the Slavery Abolition Act ten years later. So Quamina and Wray and Smith and especially Jack may not have won their battle, but pretty clearly they helped their side win the war.

Things I learned · Reading old books is good! But aside from that…

The abolition of the slave trade (well before that of slavery) was a big deal economically because, for a slave-owner, it was much cheaper to buy a slave off the boat than it was to raise a baby slave into adult servitude.

Also, a lot of the female slaves were unenthusiastic about bringing children into their life of slavery. So without a fresh crop of victims from Africa, the labor force tended to decline.

So, of course, there was plenty of illegal slave smuggling.

Manumission — the freeing of slaves — was not terribly uncommon, but became much rarer after the abolition of the slave trade. Still, it’s unsurprising that the population of free Black people in Demerara grew vigorously. But “free” didn’t work with the plantation economy.

You probably already have a bad opinion of colonial plantation slave-owners. The more you learn about them, they more you’ll loathe them. I absolutely cannot begin to understand how people could live in that role and look at their own faces in the mirror. The abuse, violence, exploitation, and rape was continuous and egregious and probably worse than a hyperoverprivileged person like me can imagine.

The white-hot screeds against the missionaries and the evils that they would inflict by teaching humans to read, and exposing them to Christian scripture, are astonishing. I quote: “Our colonies are now inundated with canting hypocritical tailors, carpenters, tinkers, cobblers, etc. who, too lazy to work for an honest livelihood in the Mother Country, and charmed with the idea of living in ease and luxury abroad, found it very convenient to become converts to the new light and volunteer to teach the Gospel without the ability to spell one of its verses.” Sounds like a bottom-feeding GOP politician snarling at Wokeness.

The planters made a lot of money… for a while. Then they became victim to falling commodity prices, financial chicanery, and the fact that the money and power were in London, held by people who didn’t care about them. Predictably, when their businesses turned sour, the suffering went mostly to the slaves.

Working in the plantation fields wasn’t the worst place a slave could find themself. Their owners regularly hired their slaves out in “task gangs” to other colonials. This was generally a terrible experience because the task-gang customer had no incentives to have a good relationship with the rented people, and typically worked them unmercifully.

The slaves were not completely without rights; there was an official called the “fiscal” whose job it was to investigate mistreatment and illegal oppression. Having nothing to lose, the slaves were extremely litigious, bombarding the fiscal with an endless stream of complaints. Most, of course, were quickly dismissed, and often the complainers were punished for speaking up. But people in desperate places will do desperate things in the pursuit of justice.

The women among the slaves had it way worse than the men. There was a culture of casual brutality against them, the slave-owners telling each other that the women were trouble-makers, recalcitrant, needed “firm discipline”. I can’t even bring myself to write about the sexual predation and the treatment of these women’s children; it’s beyond horrible.

Demerara was a long way from London, and its rulers found it convenient to ignore many of the edicts from the Mother Country urging better treatment of the slaves. Those rulers, however, were unsuccessful in trying to prevent the word about these edicts getting out. This pattern of behavior was a key factor in provoking the sense of grievance that led to the Rebellion.

The slaves came from several different African ethnic groups, and obviously (for at least the first few generations) retained some of the African languages and cultural patterns. There is evidence that the leadership of the Rebellion was mostly slaves coming from the Akan people, called “Coromantee” by the colonialists. But of these patterns and structures among the slaves, we know almost nothing, because their owners didn’t care and they had no incentive to share. The missionaries, who were eager to tell the slaves’ side of the story, ignored those stories. Sadly, they seem to have been lost.

After my reading, I feel I know Wray and Smith pretty well. I have much less insight into the real protagonists, Quamina and Jack.

The British post-Rebellion political struggles focused around the person of John Smith. The slaves were given no agency by either side. It is shocking but true that it took the imprisonment and death of one not-very-distinguished white man to launch the forces into motion that, in the end, led to a good outcome.

It’s a dark, terrible story. But there are rays of light in it. I am profoundly graceful that I live in an age where my children are at risk neither of becoming slaves nor slavers. Obviously, in the twenty-first century, we are still trying to find ways to heal the wounds inflicted on our society and culture by slavery. Anti-racism is the price of entry to the community of people trying to heal the wounds. But we’re still not very good at it.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh